Tungsten is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in low- to medium-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch). As a heavy element with an even atomic number (Z=74), it is efficiently produced by this process. Tungsten also shows significant contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. Models estimate that about 50-60% of solar tungsten comes from the s-process, and 40-50% from the r-process. This mixed production makes it an interesting tracer of both nucleosynthesis processes.

The cosmic abundance of tungsten is about 8.0×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it slightly more abundant than tantalum (Z=73) but less abundant than hafnium (Z=72). Tungsten has five natural stable isotopes (180, 182, 183, 184, 186), which is unusual for such a heavy element. The isotope W-184 is the most abundant (30.64%), followed by W-186 (28.43%). The isotopic abundances of tungsten are used in geochemistry and cosmochemistry as tracers of processes.

The hafnium-tungsten isotopic system (¹⁸²Hf → ¹⁸²W) is one of the most important chronometers for dating the earliest events in the solar system. Hafnium-182 is a short-lived radioactive isotope (half-life of 8.9 million years) that decays into tungsten-182. The importance of this system lies in the fundamental geochemical difference between these two elements: hafnium is lithophile (concentrates in silicates) while tungsten is siderophile (concentrates in metal). Thus, during the formation of a planet's metallic core, tungsten is extracted from the silicate mantle and incorporated into the core.

By measuring tungsten-182 anomalies in meteorites and lunar and terrestrial samples, cosmochemists can date the formation of the Earth's core and the differentiation of planetary bodies. Data suggest that the Earth's core formed within the first 30 to 50 million years of the solar system, and that the Moon's differentiation occurred shortly after the giant impact that formed it. The Hf-W system has also been used to date the formation of Mars, Vesta, and other bodies in the solar system.

Tungsten has two names of different origins. The name "tungsten" comes from the Swedish "tung sten" meaning "heavy stone," referring to the high density of the wolframite mineral. The name "wolfram" (and the symbol W) comes from the German "Wolf Rahm" meaning "wolf's foam," a term used by German miners in the Middle Ages who noticed that wolframite interfered with tin smelting, "devouring" the tin like a wolf devours its prey. Today, "tungsten" is used in French and English, while "wolfram" is used in German and several other languages.

Tungsten was discovered in 1783 by the Spanish brothers Fausto Elhuyar (1755-1833) and Juan José Elhuyar (1754-1796) at the Patriotic Seminary of Vergara in the Spanish Basque Country. They reduced tungsten oxide (WO₃) with charcoal to obtain the impure metal. Their discovery was independent of the earlier work of the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, who in 1781 had discovered tungstic acid from scheelite (CaWO₄) but had not isolated the metal. The Elhuyar brothers are therefore credited with the first isolation of metallic tungsten.

Early applications of tungsten were limited due to difficulties in working with it. It was not until the early 20th century that powder metallurgy methods were developed to produce ductile tungsten. A major breakthrough was made in 1903 by the Austrian chemist Alexander Just and the German physicist Franz Skaupy, who developed a process to produce ductile tungsten wire by sintering with additive metals. This development enabled the use of tungsten in electric light bulb filaments, revolutionizing lighting.

Tungsten is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 1.25 ppm (parts per million), making it as abundant as tin or molybdenum. The main tungsten ores are:

World tungsten production is about 85,000 to 90,000 tons per year (in WO₃ equivalent). China dominates production with about 80% of the world total, followed by Vietnam, Russia, Bolivia, and Rwanda. Tungsten is considered a strategic and critical metal by many countries due to its importance for defense and industry. Prices typically range from 25 to 50 dollars per kilogram for WO₃ concentrate.

Tungsten (symbol W, atomic number 74) is a transition metal of the 6th period, located in group 6 (formerly VIB) of the periodic table, along with chromium and molybdenum. Its atom has 74 protons, usually 110 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{184}\mathrm{W}\)) and 74 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁴ 6s². This configuration has four electrons in the 5d subshell and two in the 6s, characteristic of group 6 transition metals.

Tungsten is a steel-gray, shiny, very dense (19.25 g/cm³), hard metal with the highest melting point of all metals (3422 °C). It has a body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal structure at room temperature. Tungsten has a very high modulus of elasticity (about 411 GPa), making it very rigid. Its electrical conductivity is good (about 30% that of copper) and its thermal conductivity is moderate. Tungsten retains its mechanical properties at high temperatures better than almost any other metal.

Tungsten melts at 3422 °C (3695 K) - the highest melting point of all metals - and boils at 5555 °C (5828 K). It has the lowest vapor pressure of all metals at high temperatures, making it ideal for high-temperature vacuum applications. Tungsten does not undergo allotropic transformations below its melting point, retaining its body-centered cubic structure until melting.

At room temperature, tungsten is relatively inert and resistant to corrosion due to a thin protective oxide layer. It reacts with oxygen at high temperatures to form WO₃. Tungsten resists most acids but is attacked by mixtures of nitric and hydrofluoric acids. It reacts with halogens, carbon, boron, nitrogen, and sulfur at high temperatures to form various compounds.

Melting point of tungsten: 3695 K (3422 °C) - the highest of all metals.

Boiling point of tungsten: 5828 K (5555 °C).

Density: 19.25 g/cm³ - very dense, comparable to gold.

Crystal structure at room temperature: Body-centered cubic (BCC).

Modulus of elasticity: 411 GPa - very rigid.

Hardness: 7.5 on the Mohs scale (pure).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tungsten-180 — \(\,^{180}\mathrm{W}\,\) | 74 | 106 | 179.946704 u | ≈ 0.12 % | 1.8×10¹⁸ years | Alpha radioactive with extremely long half-life. Considered stable for most applications. |

| Tungsten-182 — \(\,^{182}\mathrm{W}\,\) | 74 | 108 | 181.948204 u | ≈ 26.50 % | Stable | Stable isotope, final product of hafnium-182 decay (Hf-W dating system). |

| Tungsten-183 — \(\,^{183}\mathrm{W}\,\) | 74 | 109 | 182.950223 u | ≈ 14.31 % | Stable | Stable isotope with nuclear spin 1/2, used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Tungsten-184 — \(\,^{184}\mathrm{W}\,\) | 74 | 110 | 183.950931 u | ≈ 30.64 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope in nature. |

| Tungsten-186 — \(\,^{186}\mathrm{W}\,\) | 74 | 112 | 185.954364 u | ≈ 28.43 % | Stable | Stable isotope, second most abundant in the natural mixture. |

N.B.:

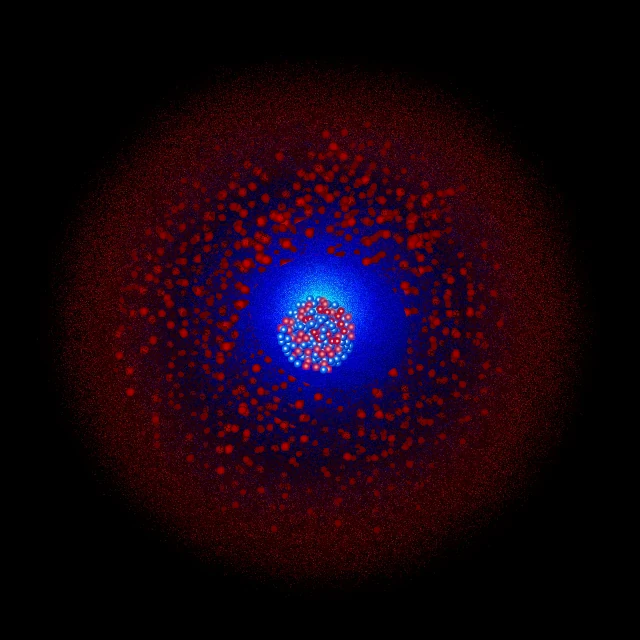

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Tungsten has 74 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁴ 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and four electrons in the 5d subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(32) P(6), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d⁴ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic screening.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 32 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴ 5d⁴. The completely filled 4f subshell and the four 5d electrons give tungsten its transition metal properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 6 electrons in the 6s² and 5d⁴ subshells.

Tungsten effectively has 6 valence electrons: two 6s² electrons and four 5d⁴ electrons. Tungsten exhibits several oxidation states, from -2 to +6, with the +6 and +4 states being the most stable and common.

In the +6 oxidation state, tungsten loses its two 6s electrons and four 5d electrons to form the W⁶⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴. This ion is diamagnetic and is found in compounds such as WO₃ (tungsten trioxide) and tungstates (WO₄²⁻). In the +4 state, tungsten forms compounds such as WO₂ (tungsten dioxide) and WCl₄ (tungsten tetrachloride).

Tungsten also has a rich chemistry of lower states and clusters. For example, in cluster compounds such as [W₆Cl₈]Cl₄, tungsten is in an average oxidation state of +2. Tungsten(0) exists in carbonyl complexes such as W(CO)₆. This diversity of oxidation states, combined with tungsten's ability to form multiple bonds with oxygen and other elements, makes it a chemically very rich and useful element in catalysis.

At room temperature, tungsten is stable in air due to a thin protective oxide layer. At high temperatures (above 400 °C), it gradually oxidizes: 2W + 3O₂ → 2WO₃. Oxidation becomes rapid above 800 °C. Tungsten(VI) oxide (WO₃) is a yellow-green solid that sublimes at 1700 °C. To protect tungsten from oxidation at high temperatures, it is often coated with tungsten silicide (WSi₂) or used in an inert atmosphere or vacuum.

Tungsten resists water and water vapor up to moderate temperatures. It resists most cold acids but is attacked by:

Tungsten dissolves in strong bases in the presence of oxidants to form soluble tungstates.

Tungsten reacts with halogens at high temperatures to form hexahalides: W + 3F₂ → WF₆ (colorless gas); W + 3Cl₂ → WCl₆ (blue-black solid). It reacts with carbon at high temperatures (>1400 °C) to form tungsten carbide WC (melting point 2870 °C) or W₂C, with nitrogen to form tungsten nitride WN, with boron to form tungsten boride WB, and with sulfur to form tungsten sulfide WS₂ (lamellar structure similar to graphite, used as a solid lubricant).

Tungsten's most remarkable property is its extremely high melting point (3422 °C), the highest of all metals. This property is due to the strong metallic bonding resulting from the contribution of 5d electrons to the conduction band and the compact body-centered cubic structure. Tungsten also retains its mechanical strength at high temperatures better than most other materials. These properties make it the material of choice for very high temperature applications.

Tungsten revolutionized lighting in the early 20th century when it replaced carbon and osmium filaments in incandescent bulbs. Before tungsten, filaments had a very limited lifespan and low light efficiency. The introduction of ductile tungsten filament in 1910 by William D. Coolidge of General Electric made it possible to produce more durable, brighter, and more efficient bulbs. This innovation was so important that tungsten became synonymous with electric lighting for nearly a century.

Tungsten filament bulbs dominated lighting for most of the 20th century. Successive improvements included filaments with controlled crystalline structure, the introduction of halogen gases (halogen bulbs) to reduce tungsten evaporation, and reflective coatings to improve efficiency. However, in the 21st century, incandescent bulbs have been largely replaced by more efficient technologies (LED, fluorescent) for energy efficiency reasons. Nevertheless, some specialized applications (projectors, ovens, scientific equipment) continue to use tungsten filaments.

The most important current application of tungsten is tungsten carbide (WC), often called "hard metal." Tungsten carbide accounts for about 60% of global tungsten consumption. It combines the hardness and wear resistance of carbides with some toughness, creating an ideal material for cutting and machining tools.

Tungsten carbide is produced by powder metallurgy: tungsten and carbon powders are mixed, pressed into the desired shape, and sintered at high temperature (1400-1600 °C). Often, a metal binder (usually 5-15% cobalt) is added to improve toughness. The resulting material has exceptional properties:

Tungsten heavy alloys (WHA), typically containing 90-97% tungsten with nickel and iron or copper as binders, are used as kinetic penetrators in anti-tank ammunition. These projectiles use their very high density (17-19 g/cm³) and mechanical strength to pierce armor. Advantages over depleted uranium penetrators include the absence of radioactive toxicity and environmental controversy.

Tungsten is also used in composite armor to protect against projectiles and shrapnel. Its high density allows it to effectively absorb kinetic energy. Tungsten-based alloys and composites are used in bulletproof vests, vehicle armor, and protection for strategic installations.

Tungsten is the standard material for electrodes in TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) welding. Tungsten electrodes, often doped with thorium, cerium, lanthanum, or zirconium, have a high melting point, low wear, and good electron emission. They allow the creation and maintenance of a stable electric arc at very high temperatures (up to 10,000 °C) without melting.

Tungsten or tungsten-copper/tungsten-silver alloy electrical contacts are used in circuit breakers, switches, and other high-performance electrical equipment. Tungsten provides resistance to electric arcs and erosion, while copper or silver ensures electrical conductivity.

Tungsten is used in semiconductors as a barrier material (diffusion barrier) and for interconnections. Its high melting temperature and low diffusivity in silicon make it an ideal material for preventing metal diffusion in semiconductor devices. Tungsten is also used as a gate material in transistors and as a contact material.

Due to its high density and high atomic number (Z=74), tungsten is an excellent absorber of X-rays and gamma rays. It is used in radiation shielding in medical (radiology), industrial (gammagraphy), and nuclear applications. Tungsten alloys are used for containers of radioactive materials and nuclear reactor shields.

In experimental fusion reactors (tokamaks), tungsten is used as a material for the divertor, the part of the reactor that must withstand the most intense heat and particle fluxes. Its high melting temperature, low tritium retention, and good thermal conductivity make it the material of choice for this extreme application.

Metallic tungsten and its insoluble compounds have low chemical toxicity. Metallic tungsten is considered biologically inert. However, some soluble tungsten compounds, particularly tungstates, have moderate toxicity. Recent studies suggest that tungsten could interfere with the metabolism of molybdenum (an essential element) due to their chemical similarities.

The extraction and processing of tungsten can generate environmental impacts:

Tungsten is widely recycled, with an estimated rate of 30-40%. Recycling sources include:

Recycling is economically attractive due to the value of tungsten and helps reduce pressure on mining resources. Recycling methods include chemical processes (acid attack, alkaline fusion) and pyrometallurgical processes.

Occupational exposure to tungsten occurs in mines, processing plants, tool and equipment manufacturers. The main routes of exposure are inhalation of dust and fumes. Studies on workers exposed to tungsten and tungsten carbide have shown potential lung effects, often associated with cobalt used as a binder in carbides. Ventilation and respiratory protection precautions are therefore necessary.