Indium was discovered in 1863 by German chemists Ferdinand Reich (1799-1882) and Hieronymus Theodor Richter (1824-1898) at the Freiberg Mining Academy in Saxony. Reich was searching for thallium in zinc ores from the region using spectroscopy, a revolutionary technique developed by Bunsen and Kirchhoff a few years earlier.

Reich, who was colorblind, asked his assistant Richter to observe the emission spectrum of a purified sample. Richter observed two intense blue lines that did not correspond to any known element. Reich and Richter recognized that they had discovered a new element, which they named indium from the Latin indicum, meaning indigo, in reference to the indigo-blue color of the spectral lines that revealed its existence.

The isolation of pure indium metal in sufficient quantity to study its properties took several years. Richter finally succeeded in producing relatively pure metal in 1867. Indium remained a laboratory curiosity for nearly a century, with no significant practical applications until the development of modern electronics in the 1940s-1950s.

Indium (symbol In, atomic number 49) is a post-transition metal in group 13 of the periodic table, along with aluminum, gallium, and thallium. Its atom has 49 protons, usually 66 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{115}\mathrm{In}\)) and 49 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p¹.

Indium is a bright silvery-white metal, extremely soft and malleable. It has a density of 7.31 g/cm³, making it moderately heavy. Indium is so soft that it can be scratched with a fingernail and marks paper like a pencil. It crystallizes in a centered tetragonal structure, unusual for a metal. Indium emits a characteristic "cry" when bent, due to the friction of crystals reorienting.

Indium melts at 157 °C (430 K), a very low melting point that makes it liquid just above the boiling point of water. It boils at 2072 °C (2345 K). Liquid indium wets glass remarkably well, a property exploited to create thin, uniform coatings and hermetic glass-metal seals.

Indium has exceptional resistance to atmospheric corrosion, hardly tarnishing in air. It is stable at room temperature in water, bases, and most dilute acids. This chemical stability, combined with its ability to form low-melting alloys and adhere to glass, makes it a valuable material for various technological applications.

Melting point of indium: 430 K (157 °C).

Boiling point of indium: 2345 K (2072 °C).

Indium is the softest metal after sodium, lithium, and lead.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indium-113 — \(\,^{113}\mathrm{In}\,\) | 49 | 64 | 112.904058 u | ≈ 4.29 % | Stable | Only stable isotope of indium, minor in natural indium. |

| Indium-115 — \(\,^{115}\mathrm{In}\,\) | 49 | 66 | 114.903878 u | ≈ 95.71 % | ≈ 4.41 × 10¹⁴ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Extremely long half-life (31,000 times the age of the universe), considered quasi-stable. |

| Indium-111 — \(\,^{111}\mathrm{In}\,\) | 49 | 62 | 110.905103 u | Synthetic | ≈ 2.80 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Gamma emitter used in SPECT medical imaging and scintigraphy. |

| Indium-114m — \(\,^{114m}\mathrm{In}\,\) | 49 | 65 | 113.904917 u | Synthetic | ≈ 49.5 days | Radioactive (isomeric transition, β⁻). Metastable state used as an industrial tracer. |

N.B.:

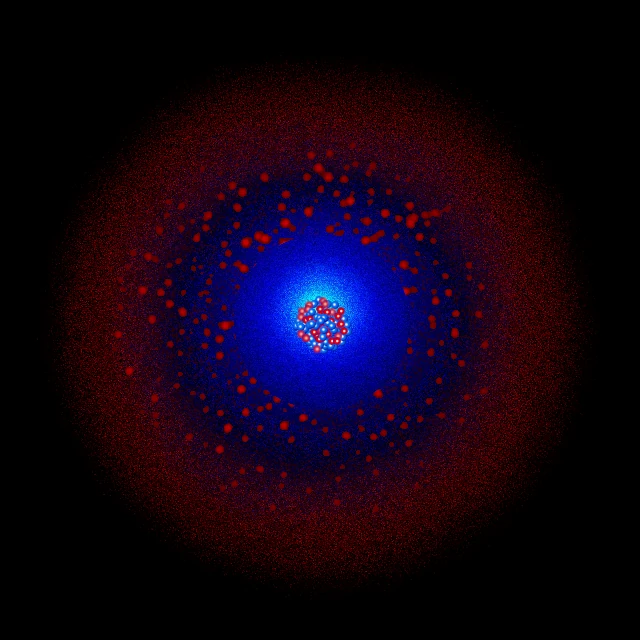

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Indium has 49 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p¹, or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(3).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O shell (n=5): contains 3 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p¹. These three electrons are the valence electrons of indium.

Indium has 3 valence electrons: two 5s² electrons and one 5p¹ electron. The most common oxidation state is +3, where indium loses its three valence electrons to form the In³⁺ ion with the configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰. This state appears in most indium compounds: indium(III) oxide (In₂O₃), indium(III) chloride (InCl₃), and indium tin oxide (ITO).

The +1 oxidation state also exists and becomes more stable as one moves down group 13, due to the inert pair effect (the 5s² electrons remain paired and do not participate in bonding). Compounds such as indium(I) chloride (InCl) and indium(I) oxide (In₂O) exist but are less stable than their indium(III) counterparts. Metallic indium corresponds to the 0 oxidation state.

Indium is remarkably stable in air at room temperature, oxidizing very slowly. A thin transparent oxide layer forms on the surface, protecting the metal from further oxidation. At high temperatures (above 800 °C), indium burns in air with a characteristic blue-violet flame, forming indium(III) oxide: 4In + 3O₂ → 2In₂O₃.

Indium reacts slowly with dilute acids to form indium(III) salts: 2In + 6HCl → 2InCl₃ + 3H₂. It dissolves more rapidly in concentrated oxidizing acids. Indium reacts with halogens at elevated temperatures to form trihalides: 2In + 3X₂ → 2InX₃. It also reacts with sulfur, selenium, and tellurium to form chalcogenides.

Indium forms many low-melting alloys with other metals. Indium-tin, indium-lead, and indium-bismuth alloys have melting points below 100 °C and are used as solders, hermetic seals, and safety fuses. Indium adheres excellently to glass and many other materials, a property exploited for glass-metal seals and coatings.

The dominant application of indium, accounting for about 70% of global demand, is indium tin oxide (ITO: Indium Tin Oxide), composed of about 90% In₂O₃ and 10% SnO₂. ITO has a unique combination of properties: exceptional optical transparency in the visible range (transmittance > 90%) and high electrical conductivity, making it an ideal transparent conductor.

Every smartphone touchscreen, tablet, laptop, and flat screen contains a thin layer of ITO (typically 100-300 nm thick) deposited on glass or plastic. This transparent layer conducts electricity, enabling the detection of capacitive touch. A typical smartphone contains about 30-50 mg of indium, a laptop screen 200-300 mg, and a large-format TV up to 1-2 grams.

The explosion of consumer electronics in the 2000s-2010s created an insatiable demand for indium. Global indium production tripled between 2000 and 2010, from 250 to over 750 tons per year. This massive demand, combined with the natural rarity of indium, has raised concerns about supply security and stimulated the search for alternatives (graphene, carbon nanotubes, silver nanowires) and improved recycling.

Indium plays a crucial role in several renewable energy technologies. CIGS thin-film solar cells (copper-indium-gallium-selenide) offer high conversion efficiencies (up to 23% in the laboratory) with much lower material consumption than crystalline silicon cells. A typical CIGS cell contains about 5-10 mg of indium per watt of power.

White LEDs, essential for energy-efficient lighting that is gradually replacing incandescent and fluorescent bulbs, use indium-gallium nitride (InGaN) semiconductors to generate blue light. The emission wavelength can be precisely adjusted by modifying the indium/gallium ratio, allowing the creation of LEDs of different colors.

This dependence of green technologies on indium creates a paradox: the energy transition to renewables and energy efficiency requires massive amounts of an extremely rare metal. Global indium production (about 800-900 tons/year) is tiny compared to the potential needs if these technologies become widespread. Indium recycling is therefore a strategic priority.

Indium is synthesized in stars mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Indium-115, the dominant quasi-stable isotope, is mainly produced by the s-process.

The cosmic abundance of indium is about 1.8×10⁻¹⁰ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the relatively rare elements in the universe. This rarity reflects its position beyond the iron peak in the nuclear stability curve.

Indium-115, although radioactive with a half-life of 441 trillion years (about 31,000 times the age of the universe), is considered quasi-stable on human and even cosmic scales. This extremely slow radioactivity manifests as β⁻ decay into stable tin-115. The exceptionally long half-life makes indium-115 unusable for radiometric dating but makes it a fascinating example of a metastable nucleus.

N.B.:

Indium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.05 ppm, making it about as rare as silver but 3 times rarer than mercury. Indium does not form economically exploitable ores of its own but is always associated with zinc, lead, copper, and tin in their ores, with typical concentrations of 0.1 to 100 ppm (parts per million).

Global indium production is about 800-900 tons per year, entirely as a byproduct of zinc refining (about 70%), lead-zinc (20%), and tin (10%). China dominates production with about 55% of the global total, followed by South Korea (25%), Japan (10%), and Canada. Indium is recovered from dust, residues, and sludges from the electrolytic refining of zinc.

Indium recycling is crucial due to its rarity and concentrated production. Currently, about 25-30% of the supply comes from recycling, mainly from the recovery of ITO in end-of-life LCD screens and production scrap. The recycling rate is expected to increase significantly in the coming decades with the improvement of recovery technologies and the increase in electronic waste volume. Indium is considered a critical material by the European Union, the United States, and other major economies.