Palladium was discovered in 1803 by the British chemist William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828), who also discovered rhodium the same year. Wollaston was working on the purification and analysis of crude platinum imported from South America. After dissolving the ore in aqua regia and precipitating the platinum, he treated the residual solution with mercury cyanide, obtaining a precipitate that he identified as a new metal.

Wollaston named this element palladium in honor of the asteroid Pallas, discovered the previous year in 1802 by the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers. Pallas itself is named after Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and war. This astronomical nomenclature was a trend of the time, also followed for cerium (named after Ceres).

In a clever and unusual manner, Wollaston chose not to immediately announce his discovery in scientific journals. Instead, he anonymously sold small quantities of palladium in a London shop, intriguing the scientific community. Some chemists, including the famous Richard Chenevix, claimed that palladium was merely an alloy of platinum and mercury rather than a true element. Wollaston finally revealed his authorship of the discovery in 1805, irrefutably demonstrating the elemental nature of palladium.

Palladium (symbol Pd, atomic number 46) is a transition metal in group 10 of the periodic table, belonging to the platinum group metals. Its atom has 46 protons, usually 60 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{106}\mathrm{Pd}\)) and 46 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰.

Palladium is a bright silvery-white metal, the lightest and softest of the platinum group metals. It has a density of 12.02 g/cm³, significantly lower than that of platinum (21.45 g/cm³). Palladium crystallizes in a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure. It is ductile and malleable, and can be rolled into very thin sheets and drawn into wires.

Palladium melts at 1555 °C (1828 K) and boils at 2963 °C (3236 K). It has the lowest melting point of all platinum group metals, which facilitates its processing and alloying. Palladium also has high thermal and electrical conductivity, as well as a low coefficient of thermal expansion.

The most remarkable property of palladium is its extraordinary ability to absorb hydrogen. At room temperature, palladium can absorb up to 900 times its own volume of hydrogen gas, forming palladium hydride (PdHₓ where x can reach 0.7). This unique property makes palladium an essential material for hydrogen storage, purification, and catalysis.

Melting point of palladium: 1828 K (1555 °C).

Boiling point of palladium: 3236 K (2963 °C).

Palladium can absorb up to 900 times its volume in hydrogen gas.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium-102 — \(\,^{102}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 56 | 101.905609 u | ≈ 1.02 % | Stable | Lightest and rarest stable isotope of natural palladium. |

| Palladium-104 — \(\,^{104}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 58 | 103.904036 u | ≈ 11.14 % | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope of natural palladium. |

| Palladium-105 — \(\,^{105}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 59 | 104.905085 u | ≈ 22.33 % | Stable | Third most abundant stable isotope of natural palladium. |

| Palladium-106 — \(\,^{106}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 60 | 105.903486 u | ≈ 27.33 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of palladium, representing more than a quarter of the total. |

| Palladium-108 — \(\,^{108}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 62 | 107.903892 u | ≈ 26.46 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope, almost as common as Pd-106. |

| Palladium-110 — \(\,^{110}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 64 | 109.905153 u | ≈ 11.72 % | Stable | Heaviest stable isotope of natural palladium. |

| Palladium-107 — \(\,^{107}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 61 | 106.905133 u | Synthetic | ≈ 6.5 × 10⁶ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Fission product. Extinct isotope present during the formation of the solar system. |

| Palladium-103 — \(\,^{103}\mathrm{Pd}\,\) | 46 | 57 | 102.906087 u | Synthetic | ≈ 17.0 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Used in brachytherapy to treat prostate cancer. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

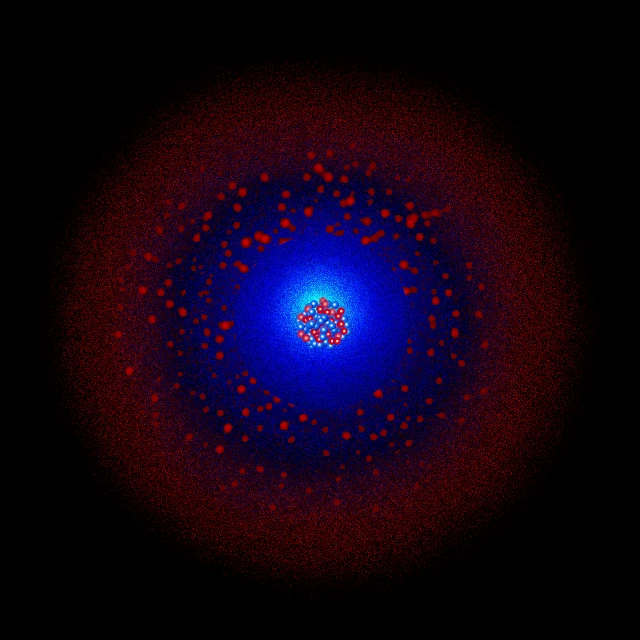

Palladium has 46 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰, or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰. This configuration is unique because palladium is the only element in its period that does not have electrons in the 5s subshell, the 4d subshell being completely filled. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell constitutes the valence shell of palladium.

Palladium has 10 valence electrons in its complete 4d¹⁰ subshell. Despite this d10 configuration generally associated with low reactivity, palladium is chemically active because the 4d electrons can be easily excited or lost. Palladium mainly exhibits oxidation states +2 and +4, although the +2 state is by far the most common and stable.

The +2 oxidation state appears in most palladium compounds, notably palladium(II) chloride (PdCl₂), palladium(II) oxide (PdO), and countless coordination complexes. The +4 state exists in a few compounds such as hexafluoropalladate(IV) (PdF₆²⁻). Oxidation states 0, +1, and +3 also exist in some organometallic complexes.

Palladium is relatively resistant to corrosion at room temperature and does not tarnish in air under normal conditions. It resists many dilute acids but dissolves slowly in concentrated nitric acid and more rapidly in aqua regia. At high temperatures, palladium slowly oxidizes to form palladium(II) oxide (PdO), a black compound that decomposes above 750 °C.

The most extraordinary property of palladium is its interaction with hydrogen. Palladium absorbs hydrogen gas reversibly, forming a Pd-H system where hydrogen atoms occupy the interstitial sites of the crystal lattice. At room temperature and atmospheric pressure, palladium can form PdH₀.₆, and at low temperature and high pressure, the composition can reach PdH₁.

This hydrogen absorption causes an expansion of the crystal lattice (about 10% volume increase) and significantly changes the physical properties of palladium: decreased electrical conductivity, mechanical embrittlement, and color change. Hydrogen-loaded palladium can release pure hydrogen by heating or under vacuum, which is exploited for hydrogen purification to 99.9999% purity.

Palladium is the only metal that allows the selective passage of hydrogen through a membrane at high temperature. This unique property is exploited in palladium membrane separators to produce ultra-pure hydrogen for the semiconductor industry, fuel cells, and electronics.

Palladium plays a central role in modern homogeneous catalysis. In 2010, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Richard F. Heck, Ei-ichi Negishi, and Akira Suzuki for the development of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, which allow the formation of carbon-carbon bonds with exceptional precision and efficiency.

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions have revolutionized organic synthesis. The Suzuki-Miyaura reaction couples boronic acids with organic halides, the Heck reaction couples alkenes with aromatic halides, and the Negishi reaction uses organozinc compounds. These transformations are now indispensable standard tools in pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and materials chemistry.

Palladium catalysts enable the synthesis of complex molecules that are impossible to obtain by other methods. More than 25% of the drugs marketed today are manufactured using at least one palladium-catalyzed step. OLED screens, conductive polymers, and many advanced materials also depend on these palladium-catalyzed reactions.

Palladium has become the most in-demand platinum group metal, surpassing platinum since 2016. Automotive demand for palladium has exploded with the shift from diesel engines (which primarily use platinum) to gasoline engines (which use palladium and rhodium) following the Dieselgate scandal and the tightening of emission standards.

The price of palladium has seen a spectacular rise: around $200 per troy ounce in 2002, $1000-$1500 in the 2010s, then an explosion to over $3000 in 2019-2020, surpassing the price of gold for the first time and becoming the most expensive precious metal. The price has stabilized around $1000-$2000 per ounce since 2022-2024 following increased recycling and partial substitution with platinum.

Palladium supply is geographically concentrated: about 40% comes from Russia (Norilsk mines), 38% from South Africa (Bushveld complex), and the rest from Canada and the United States. This geographical concentration, combined with geopolitical tensions, creates significant price volatility. Recycling of used automotive catalysts provides about 30% of the annual supply.

Palladium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. The six stable isotopes of palladium reflect the contributions of these different processes.

The cosmic abundance of palladium is about 1.4×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This moderate abundance for a platinum group metal is explained by its favorable position in the nuclear stability curve.

Palladium-107, an extinct radioactive isotope (half-life 6.5 million years), was present during the formation of the solar system. Its decay product, silver-107, shows measurable excesses in some primitive meteorites. The initial ¹⁰⁷Pd/¹⁰⁸Pd ratio provides constraints on the time between the last nucleosynthesis events and the formation of the first solids in the solar system, estimated at a few million years.

Isotopic variations of palladium in meteorites also provide information on the heterogeneity of the primitive solar nebula and the relative contributions of the s and r processes. Spectral lines of palladium are observable in some stars enriched in heavy elements, allowing the tracing of galactic chemical enrichment.

N.B.:

Palladium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.015 ppm, about 100 times rarer than silver but 5 times more abundant than gold. It does not form its own ores but is always associated with other platinum group metals, mainly in nickel-copper deposits and layered ultramafic rock complexes.

Global palladium production is about 210 tons per year. Russia is the largest producer (about 40%), followed by South Africa (38%), Canada, and the United States. About 90% of palladium is extracted as a byproduct of nickel and platinum extraction. Recycling of automotive catalysts provides about 30% of the total supply, a proportion that is constantly increasing.

Palladium is extracted from platinum group metal concentrates through hydrometallurgical processes involving dissolution in aqua regia, selective precipitation of ammonium palladium chloride ((NH₄)₂PdCl₆), followed by reduction with hydrazine or formic acid. Pure palladium (99.95%) is obtained after electrolytic refining or repeated dissolution-reprecipitation.