Francium is an element produced exclusively by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during extreme astrophysical events such as supernovae or neutron star mergers. However, because all its isotopes are radioactive with very short half-lives (the most stable, \(^{223}\mathrm{Fr}\), has a half-life of only 22.00 minutes), no primordial francium remains in the universe since the formation of the solar system. All francium produced at that time decayed billions of years ago. The francium present on Earth today (in infinitesimal quantities) is constantly recreated in two ways:

\(^{223}\mathrm{Fr}\) (historically called AcK, for "actinium K") is the natural francium isotope with the longest half-life. It decays with a half-life of 22.00 minutes mainly by beta-minus decay (99.994%) to radium-223, and very weakly (0.006%) by alpha emission to astatine-219. Its presence is linked to secular equilibrium with its parent, actinium-227 (half-life 21.772 years). It is estimated that at any given time, less than one gram of francium-223 is present in the entire Earth's crust, dispersed in uranium ores.

Despite (or because of) its extreme instability, francium is a fascinating object of study for physicists. As the last alkali, it has a single valence electron in an s orbital (7s¹), which makes it a "simple" atom from a quantum mechanical point of view, but with very pronounced relativistic effects due to the strong nuclear charge. Precise measurement of its atomic properties (energy levels, moments, hyperfine structure) allows testing with great precision the predictions of quantum electrodynamics (QED) in intense electromagnetic fields. These tests contribute to the search for new physics beyond the Standard Model.

The existence of element 87, an alkali heavier than cesium, was predicted by Dmitri Mendeleev who named it "eka-cesium". Its search was arduous and marked by several false discoveries in the early 20th century (such as "virginium" or "moldavium"), because its expected chemical properties (extreme reactivity, great instability) made it elusive.

The discovery goes to French physicist and chemist Marguerite Perey (1909-1975), then assistant to Marie Curie at the Radium Institute (Paris). In 1939, while purifying a sample of actinium-227, she noticed an abnormal radioactive activity (beta emission) that could not be attributed to any known isotope. After months of meticulous chemical analyses, she demonstrated that this activity was due to a new element, produced by alpha decay of actinium-227 (1.38% branch):

\(^{227}\mathrm{Ac} \xrightarrow[\alpha]{} ^{223}\mathrm{Fr}\)

She confirmed that it was indeed the missing last alkali, and gave it the name "francium" in honor of her country, France, thus following the tradition of the Curies (polonium) and Debierne (actinium). Her thesis, defended in 1946, consolidated this discovery. Marguerite Perey was the first woman elected to the Academy of Sciences (1962), but not to the French Academy.

The study of francium was limited by the infinitesimal quantities available naturally. In the 1970s-80s, the development of particle accelerators made it possible to produce heavier isotopes in larger quantities (although still infinitesimal on a macroscopic scale) through reactions such as \(^{197}\mathrm{Au} + ^{18}\mathrm{O} \rightarrow \,^{210}\mathrm{Fr} + 5n\). This paved the way for more advanced physical studies.

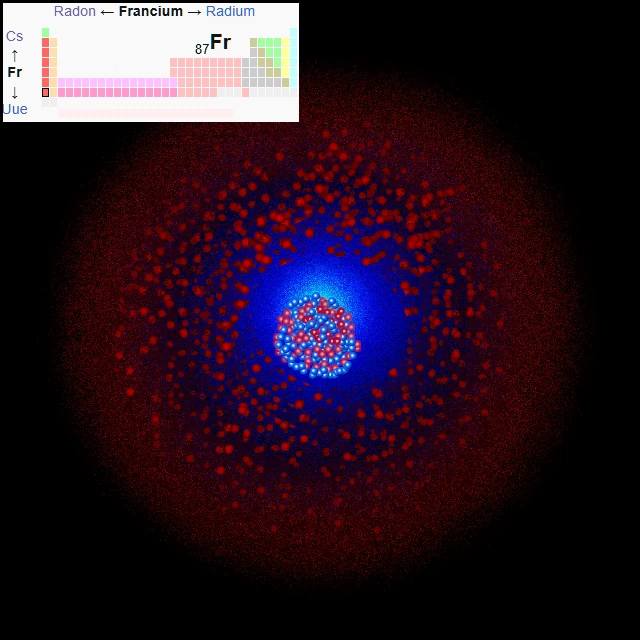

Today, francium is produced exclusively artificially in a few specialized laboratories around the world (Stony Brook in the United States, TRIUMF in Canada, RIKEN in Japan, etc.). The most common method uses an accelerated oxygen-18 beam at about 100 MeV to bombard a gold-197 target. The fusion-evaporation reaction produces heavy francium isotopes (such as \(^{210}\mathrm{Fr}\) to \(^{213}\mathrm{Fr}\)), which are then extracted, separated and trapped in experimental devices as individual atoms or small clouds.

The quantities produced are so small that they are measured in number of atoms per second (typically \(10^4\) to \(10^6\) atoms/s), and never in grams. It is therefore impossible to have a visible or manipulable sample of metallic francium.

Francium (symbol Fr, atomic number 87) is an element of group 1, that of alkali metals. It is the heaviest and most radioactive member of this family, which includes lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, cesium and the very recent nihonium (probably not alkali). Its atom has 87 protons and, depending on the isotope, 123 to 150 neutrons. The natural isotope \(^{223}\mathrm{Fr}\) has 136 neutrons. Its electron configuration is [Rn] 7s¹, with a single valence electron in the 7s shell.

Due to the impossibility of obtaining a macroscopic quantity, most of the physical properties of francium have never been directly measured. They are deduced by extrapolation of alkali group trends, theoretical calculations and spectroscopic studies on individual atoms.

Estimated melting point: ~300 K (~27 °C).

Estimated boiling point: ~950 K (~677 °C).

These values are very uncertain.

Atomic number: 87.

Group: 1 (Alkali metals).

Electron configuration: [Rn] 7s¹.

Oxidation state: +1 (exclusive).

Most stable isotope: \(^{223}\mathrm{Fr}\) (T½ = 22.00 min).

Appearance (predicted): Silvery metal, extremely reactive.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Production / Occurrence | Half-life / Decay mode | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Francium-212 — \(^{212}\mathrm{Fr}\) | 87 | 125 | 212.012s u | Synthetic | 20.0 min (β⁻, 99.45%; α, 0.55%) | Synthetic isotope with medium lifetime. |

| Francium-221 — \(^{221}\mathrm{Fr}\) | 87 | 134 | 221.014s u | Natural trace (Np-237 chain) | 4.9 min (α, 99.65%; β⁻, 0.35%) | Present in trace amounts in ores containing neptunium-237. |

| Francium-222 — \(^{222}\mathrm{Fr}\) | 87 | 135 | 222.017s u | Synthetic | 14.2 min (β⁻) | Synthetic isotope. |

| Francium-223 — \(^{223}\mathrm{Fr}\) | 87 | 136 | 223.019736 u | Natural (U-235 chain) and synthetic | 22.00 min (β⁻, 99.994%; α, 0.006%) | Most stable natural isotope. Discovered by Marguerite Perey. Longest half-life. Used for certain studies. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Francium has 87 electrons distributed over seven electron shells. Its electron configuration [Rn] 7s¹ is remarkably simple: it consists of the configuration of radon (a noble gas) plus one additional electron in the 7s shell. This can also be written: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(8) Q(1), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁶ 7s¹.

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 8 electrons (6s² 6p⁶).

Q shell (n=7): 1 electron (7s¹).

Francium has a single valence electron (7s¹). This electron is very far from the nucleus and is weakly bound due to the significant shielding created by the 86 electrons of the inner shells (noble gas configuration). Consequently:

These properties make francium the archetype of the extreme alkali metal: the most electropositive, the most reactive, and the one whose chemistry is dominated by the Fr⁺ ion.

Like other alkalis, francium would exist chemically only in the +1 oxidation state. The Fr⁺ ion would be the largest alkali cation, with an estimated ionic radius of 180 pm. Its chemistry in aqueous solution would be simple and similar to that of cesium (Cs⁺), but with some differences:

Francium metal, if it could be isolated, would be explosively reactive:

In practice, these reactions can never be observed on a visible sample.

The chemistry of francium is studied by trace radiochemistry and spectroscopy on trapped cold atoms techniques. The behavior of a few atoms is monitored (by their radioactivity) in ion exchange columns or during coprecipitations. These studies confirmed that its behavior is very close to that of cesium, with perhaps a slight difference in partition coefficients due to its larger size.

Francium has strictly no practical application outside of fundamental research, due to its extreme rarity and instability. Its "applications" are therefore limited to the field of pure science:

Like any beta/alpha emitter, francium incorporated into the body would be toxic. However, this risk is purely theoretical:

Handling is done in controlled nuclear laboratories, with shields for the ion beam and procedures to manage activated targets. Separation chemistry is performed in glove boxes or closed enclosures.

Francium will forever remain a laboratory element, a scientific curiosity at the borders of stability. Its interest lies in what it teaches us about the fundamental laws of physics. Current and future research aims to: