Tellurium was discovered in 1782 by the Austrian mineralogist Franz-Joseph Müller von Reichenstein (1740-1825) in gold ores from Transylvania. Müller worked as a mine inspector for the Austrian government when he analyzed a particular ore extracted from the mines of Zlatna (present-day Romania). He identified an unusual metallic substance that he could not fully classify, although he was convinced he had discovered a new element.

His work was confirmed and expanded by the German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1743-1817) in 1798, who definitively isolated the element and named it tellurium, from the Latin tellus meaning "earth." This name was chosen in reference to the planet Earth, creating a parallel with uranium (named after Uranus) discovered a few years earlier by Klaproth himself. The chemical symbol Te was adopted from the outset.

The classification of tellurium as a metalloid was established in the 19th century when chemists recognized its intermediate properties between metals and non-metals. Tellurium shares many chemical similarities with selenium and sulfur, its neighbors in group 16 of the periodic table, but exhibits a more pronounced metallic character.

N.B.:

Tellurium is extremely rare in the Earth's crust, with an average concentration of about 0.001 ppm (one part per billion), making it one of the rarest elements, comparable in rarity to platinum and about eight times rarer than gold. This extraordinary rarity contrasts with its growing importance in modern technologies.

Tellurium is almost never found in its native state. It is mainly obtained as a byproduct of electrolytic copper refining, where it accumulates in the anode slime with gold, silver, and selenium. The main tellurium ores include calaverite (AuTe₂), sylvanite ((Au,Ag)₂Te₄), tetradymite (Bi₂Te₂S), and tellurite (TeO₂).

Global tellurium production is about 450 to 550 tons per year, almost entirely as a byproduct of copper and lead metallurgy. China, Japan, Canada, Russia, and the United States are the main producers. This very limited production and dependence on copper production make tellurium one of the most critical materials for emerging technologies, particularly thin-film solar panels.

Tellurium (symbol Te, atomic number 52) is a metalloid in group 16 of the periodic table, along with oxygen, sulfur, selenium, and polonium. Its atom has 52 protons, usually 78 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{130}\mathrm{Te}\)), and 52 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁴.

Tellurium is a silvery-gray crystalline solid with a pronounced metallic luster, more metallic than selenium but retaining metalloid properties. It has a density of 6.24 g/cm³, making it moderately heavy. Tellurium crystallizes in a trigonal hexagonal structure forming helical chains of atoms, similar to the structure of selenium. It is brittle and easily pulverized under pressure.

Tellurium melts at 449.51 °C (722.66 K) and boils at 988 °C (1261 K). Its electrical conductivity increases with temperature and under light exposure, a characteristic photoconductivity property of semiconductors. Tellurium is one of the best thermal conductors among metalloids.

Tellurium exhibits low electrical conductivity at room temperature, about a million times lower than that of copper, but this conductivity increases significantly with temperature, typical behavior of semiconductors. Pure tellurium has a bright metallic luster that slowly tarnishes in air.

Melting point of tellurium: 722.66 K (449.51 °C).

Boiling point of tellurium: 1261 K (988 °C).

Tellurium exhibits photoconductive properties, its resistivity decreasing under illumination.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tellurium-120 — \(\,^{120}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 68 | 119.904020 u | ≈ 0.09% | Stable | Lightest stable isotope of tellurium, extremely rare. |

| Tellurium-122 — \(\,^{122}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 70 | 121.903044 u | ≈ 2.55% | Stable | Minor stable isotope of natural tellurium. |

| Tellurium-123 — \(\,^{123}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 71 | 122.904270 u | ≈ 0.89% | Stable | Only stable isotope with an odd number of neutrons. |

| Tellurium-124 — \(\,^{124}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 72 | 123.902818 u | ≈ 4.74% | Stable | Common stable isotope of natural tellurium. |

| Tellurium-125 — \(\,^{125}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 73 | 124.904431 u | ≈ 7.07% | Stable | Stable isotope representing about 7% of natural tellurium. |

| Tellurium-126 — \(\,^{126}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 74 | 125.903312 u | ≈ 18.84% | Stable | Second most abundant isotope of natural tellurium. |

| Tellurium-128 — \(\,^{128}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 76 | 127.904463 u | ≈ 31.74% | ≈ 2.2×10²⁴ years | Radioactive (β⁻β⁻), longest measured half-life. Considered stable in practice. |

| Tellurium-130 — \(\,^{130}\mathrm{Te}\,\) | 52 | 78 | 129.906224 u | ≈ 34.08% | ≈ 8×10²⁰ years | Radioactive (β⁻β⁻), most abundant isotope despite theoretical radioactivity. |

N.B.:

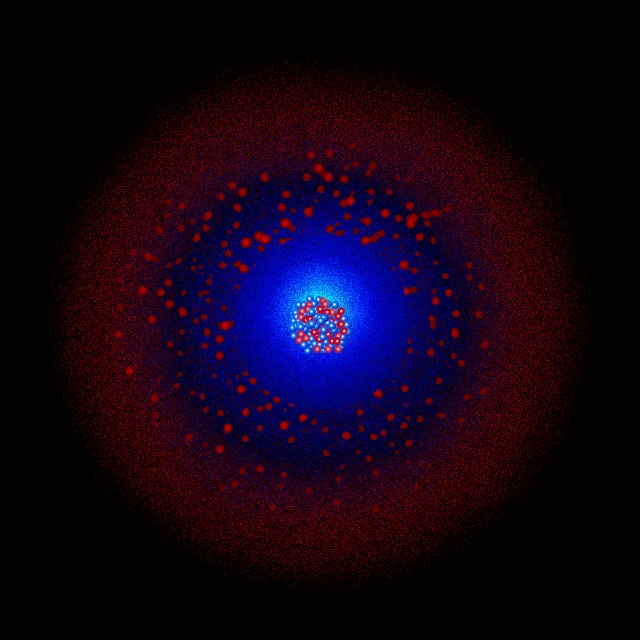

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Tellurium has 52 electrons distributed across five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁴, or simplified as: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁴. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(6).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N Shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O Shell (n=5): contains 6 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁴. These six electrons are the valence electrons of tellurium.

Tellurium has 6 valence electrons: two 5s² electrons and four 5p⁴ electrons. The main oxidation states are -2, +4, and +6. The -2 state appears in metallic tellurides (such as CdTe, ZnTe, Bi₂Te₃) where tellurium acts as an electron acceptor, forming the Te²⁻ ion.

The +4 state is the most common in oxygenated compounds, appearing in tellurium dioxide (TeO₂) and tellurous acid (H₂TeO₃). The +6 state exists in more oxidized compounds such as tellurium trioxide (TeO₃) and telluric acid (H₆TeO₆), where tellurium uses all its valence electrons. Metallic tellurium corresponds to the 0 oxidation state.

Tellurium is moderately stable in air at room temperature, slowly oxidizing to form a thin surface layer of dioxide. At high temperatures (above 450 °C), tellurium burns in air with a bluish-green flame, forming tellurium dioxide (TeO₂) which is released as white smoke: Te + O₂ → TeO₂. This combustion produces a characteristic unpleasant odor.

Tellurium reacts with halogens to form tetrahalides: Te + 2Cl₂ → TeCl₄ (tetrachloride) or dihalides under controlled conditions. Tellurium resists dilute non-oxidizing acids but dissolves in concentrated nitric acid and hot sulfuric acid to form tellurous acid.

With hydrogen, tellurium forms hydrogen telluride (H₂Te), an extremely foul-smelling toxic gas, much less stable than hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). Tellurium reacts directly with many metals at high temperatures to form metallic tellurides, important compounds in semiconductor technology.

The most important and fastest-growing application of tellurium is the production of thin-film cadmium telluride (CdTe) photovoltaic cells. This technology currently accounts for 40-50% of global tellurium demand, and this proportion is rapidly increasing with the expansion of solar energy.

CdTe solar panels offer several significant advantages: lower production cost than crystalline silicon panels, better performance at high temperatures and low light conditions, less energy-intensive manufacturing process, and favorable temperature coefficient. Major manufacturers like First Solar have demonstrated the commercial viability of this technology on a large scale.

The conversion efficiency of commercial CdTe cells reaches 16-19%, with laboratory records exceeding 22%. A typical 100-watt CdTe solar panel contains about 6-10 grams of tellurium. With the global goal of energy transition, the demand for tellurium for photovoltaics could increase by several orders of magnitude, raising concerns about long-term availability.

The second major technological application of tellurium is in thermoelectric materials, particularly bismuth telluride (Bi₂Te₃) and its alloys. These materials directly convert heat into electricity (Seebeck effect) or electricity into a temperature difference (Peltier effect), without moving parts.

Bismuth telluride-based Peltier devices are widely used for cooling sensitive electronic components, portable refrigerators, automotive seat air conditioners, and temperature control in scientific instrumentation. Thermoelectric generators using Bi₂Te₃ convert waste heat into electricity in automotive, aerospace, and space applications.

Bismuth telluride has one of the highest thermoelectric figures of merit (ZT) at room temperature, making it ideal for these applications. Ongoing research on advanced thermoelectric materials could significantly increase the demand for tellurium in the coming decades, particularly for thermal energy recovery in vehicles and industry.

Tellurium and its compounds exhibit moderate toxicity. Although less toxic than selenium or arsenic, tellurium can accumulate in the body and cause characteristic effects. The most notable effect of tellurium exposure is the development of intense and persistent garlic-like breath, caused by the production of dimethyl telluride exhaled by the lungs, even at very low doses.

Occupational exposure to tellurium mainly occurs in copper refining, electronics manufacturing, and solar panel production industries. Symptoms of poisoning include fatigue, drowsiness, dry mouth, loss of appetite, and a metallic taste, in addition to the characteristic breath. Chronic effects may include neurological and hematological disorders.

Cadmium telluride (CdTe) used in solar panels raises environmental concerns due to the presence of cadmium, a highly toxic heavy metal. However, cadmium telluride is extremely stable and insoluble, minimizing the risk of cadmium leaching. Manufacturers have developed recycling programs to recover tellurium and cadmium at the end of the panels' life.

Tellurium is one of the rarest elements in the Earth's crust, with an average abundance of about 0.001 ppm (one part per billion). This extraordinary rarity, comparable to that of platinum and eight times greater than that of gold, poses major challenges for supply in the face of growing demand for clean technologies.

Global tellurium production is limited to about 450-550 tons per year, almost entirely obtained as a byproduct of electrolytic copper refining. This dependence means that the supply of tellurium is linked to copper production rather than the demand for tellurium itself, creating structural supply constraints.

Projections show that massive adoption of CdTe solar panels could quickly deplete accessible tellurium reserves. Terawatt-scale solar deployment scenarios would require tens of thousands of tons of tellurium, far exceeding current production. This limitation could hinder the expansion of CdTe technology or require innovations in recycling and material use efficiency.

Tellurium is classified as a critical material by the European Union, the United States, and Japan due to its technological importance combined with its extreme rarity and the geographical concentration of its production. The development of alternative technologies and improved recycling are considered essential for long-term supply security.

Tellurium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with significant contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. The eight stable isotopes of tellurium have diverse nucleosynthetic origins.

The cosmic abundance of tellurium is extremely low, about 5×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, placing it among the rarest elements in the universe. This rarity is explained by tellurium's position in a less favorable region of the nuclear stability curve and by production barriers in stellar nucleosynthesis processes.

Spectral lines of neutral tellurium (Te I) and ionized tellurium (Te II) are rarely observed in stellar spectra due to the very low cosmic abundance of this element. Nevertheless, traces of tellurium have been detected in certain chemically peculiar stars enriched in heavy elements, allowing the study of nucleosynthesis processes and galactic chemical evolution.

The isotope ¹²⁸Te has the longest measured half-life of all radioactive isotopes, about 2.2×10²⁴ years, more than a trillion times the age of the universe. This extremely slow double beta decay makes ¹²⁸Te an ideal system for studying fundamental nuclear processes and testing nuclear physics predictions.