Lead plays a unique cosmological and geological role: it is the stable endpoint of three of the four main natural radioactive decay chains. The stable isotopes of lead are the final products of the decay of uranium and thorium:

The fourth stable isotope, \(^{204}\mathrm{Pb}\), is not radiogenic; it is called "primordial" and has been present since the formation of the solar system. Thus, almost all the lead on Earth today was formed by the radioactive decay of heavier elements over billions of years.

These decays make the uranium/thorium-lead isotopic system one of the most powerful and widely used geological clocks. By measuring the ratios \(^{206}\mathrm{Pb}/^{238}\mathrm{U}\), \(^{207}\mathrm{Pb}/^{235}\mathrm{U}\), and \(^{207}\mathrm{Pb}/^{206}\mathrm{Pb}\) in a rock or mineral (such as zircon), geochronologists can accurately date events ranging from the formation of the solar system (4.567 Ga) to recent geological processes a few million years old. This method established the age of the Earth at about 4.54 billion years.

Lead isotopic ratios also serve as a geochemical tracer. Since different geological reservoirs (mantle, continental crust, ore deposits) have distinct lead isotopic signatures, the origin of magmas, sediments, or even historical atmospheric pollution (the lead isotopic signatures of 1970s car exhaust differ from those of Roman mines) can be traced.

The cosmic abundance of lead is about 1.0×10⁻¹¹ that of hydrogen. It is synthesized in stars mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in AGB stars, with a significant contribution from the r-process during supernovae. It is the heaviest stable element efficiently produced by the s-process, making it an abundance peak in the element spectrum. Its doubly magic nucleus (Z=82, complete proton shell) gives it exceptional stability.

The chemical symbol Pb comes from the Latin "plumbum", which also gave us the words "plumber" and "plumbing". In alchemy, lead was associated with the planet Saturn and symbolized heaviness, melancholy, and the raw material to be transmuted into gold (the goal of the "Great Work").

Lead is one of the first metals worked by humans, along with copper and gold. Its ease of extraction (simple reduction of the galena ore, PbS) and its properties (malleable, fusible, corrosion-resistant) made it a material of choice for the Romans. They used it massively for:

Some historians suggest that chronic lead poisoning (saturnism) may have contributed to the decline of the Roman elite, affecting fertility and intellectual abilities.

The use of lead continued: cathedral roofs and stained glass, printing type, ammunition (bullets, shot), paint pigments (white lead for white, lead chromate for yellow), and weights. The Industrial Revolution greatly increased its production and uses, especially with the advent of lead paint and leaded gasoline in the 20th century.

The main lead ore is galena (PbS), a cubic metallic gray mineral often associated with sphalerite (ZnS) and silver. The main producing countries are China (about half of world production), Australia, the United States, Peru, and Mexico. Annual mining production is about 4.5 million tons. A significant portion (over 50%) now comes from recycling, especially from batteries.

The price of lead is moderate and generally follows economic cycles and demand from the automotive industry (for batteries).

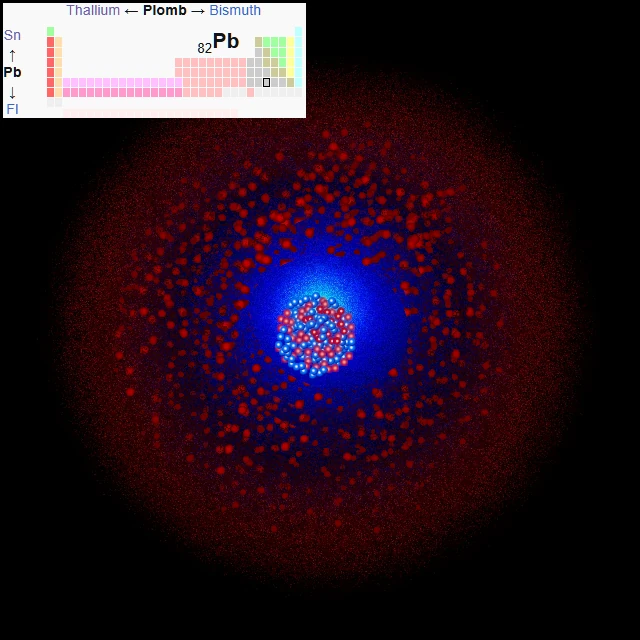

Lead (symbol Pb, atomic number 82) is a post-transition element, located in group 14 (carbon group) of the periodic table, along with carbon, silicon, germanium, and tin. It is the heaviest and most metallic member of this group. Its atom has 82 protons, usually 125 to 126 neutrons (for isotopes \(^{207}\mathrm{Pb}\) and \(^{208}\mathrm{Pb}\)), and 82 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p². It has four valence electrons (6s² 6p²).

Lead is a bluish-gray, dense, soft, malleable metal with a low melting point.

Lead crystallizes in a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure.

Lead melts at 327.46 °C (600.61 K) and boils at 1749 °C (2022 K). Its wide temperature range in the solid state and ease of molding have historically facilitated its use.

Lead is a rather unreactive metal due to the formation of a protective layer of oxide, carbonate, or sulfate on its surface. It resists atmospheric corrosion and attack by many chemical agents, especially concentrated sulfuric acid (used in batteries). However, it is attacked by nitric and acetic acids.

Density: 11.34 g/cm³.

Melting point: 600.61 K (327.46 °C).

Boiling point: 2022 K (1749 °C).

Crystal structure: Face-centered cubic (FCC).

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p².

Main oxidation states: +2 and +4.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead-204 — \(^{204}\mathrm{Pb}\) | 82 | 122 | 203.973044 u | ≈ 1.4 % | Stable | Only stable non-radiogenic isotope. "Primordial" isotope, used as a reference in geochronology calculations. |

| Lead-206 — \(^{206}\mathrm{Pb}\) | 82 | 124 | 205.974465 u | ≈ 24.1 % | Stable | Stable final product of \(^{238}\mathrm{U}\) decay. Major radiogenic isotope. |

| Lead-207 — \(^{207}\mathrm{Pb}\) | 82 | 125 | 206.975897 u | ≈ 22.1 % | Stable | Stable final product of \(^{235}\mathrm{U}\) decay. Crucial for \(^{207}\mathrm{Pb}/^{206}\mathrm{Pb}\) dating. |

| Lead-208 — \(^{208}\mathrm{Pb}\) | 82 | 126 | 207.976652 u | ≈ 52.4 % | Stable | Stable final product of \(^{232}\mathrm{Th}\) decay. Most abundant and heaviest stable isotope known (doubly magic nucleus). |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Lead has 82 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p² has four valence electrons in the 6th shell (s² p²), like carbon or silicon, but with marked relativistic effects that make the 6s² pair very inert ("inert pair effect"). This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(4), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p².

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 4 electrons (6s² 6p²).

Lead has 4 valence electrons (6s² 6p²). However, due to the inert pair effect, the +2 oxidation state (where only the 6p² pair is lost) is more stable and common than the +4 state (which would require losing the 6s² pair as well, which is stabilized).

This chemistry contrasts with that of carbon, where the +4 state is the rule, illustrating the evolution of properties within a periodic table group.

Freshly cut lead has a metallic luster that quickly tarnishes in air, forming a thin gray layer of lead(II) oxide (PbO) and basic lead carbonate (2PbCO₃·Pb(OH)₂), which protects it from further oxidation. When heated in air, it first forms litharge (PbO, yellow), then at higher temperatures, red lead (Pb₃O₄), a historical pigment.

Invented in 1859 by Gaston Planté, it is the first rechargeable battery. Its success lies in its reliability, low cost, and high capacity to deliver intense currents.

Principle:

Negative electrode: Spongy lead (Pb).

Positive electrode: Lead dioxide (PbO₂).

Electrolyte: Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) at ~30%.

Discharge reaction: Pb + PbO₂ + 2H₂SO₄ → 2PbSO₄ + 2H₂O

Applications are ubiquitous: vehicle starting (SLI), backup power (UPS), electric vehicles (traction), off-grid photovoltaic systems. The recycling of these batteries is very efficient (>99% in developed countries).

The high density and atomic number of lead make it an ideal shield against ionizing radiation. It effectively absorbs X-rays and gamma rays. It is used in the form of:

Lead is a cumulative toxin with no known biological function. It interferes with many enzymatic processes by substituting for other essential metal ions, particularly calcium (Ca²⁺) and zinc (Zn²⁺). Its main targets are:

There is no demonstrated safe threshold, especially for children. The WHO considers a blood lead level (BLL) above 5 µg/dL in children to be concerning. Health authorities recommend the "precautionary principle": reduce exposure as much as possible.

Lead emitted into the atmosphere deposits on soils and waters. It is not very mobile in most soils and accumulates in the surface layers. In acidic environments, it can become more mobile and contaminate groundwater. It does not degrade; its persistence is millennial.

Notable cases include the city of Kabwe in Zambia (pollution from the old lead mine), the West Dallas neighborhood in the United States (former smelter), and the widespread contamination from leaded gasoline, whose fallout is measurable in polar ice and lake sediments worldwide.

This is a model of the circular economy. Used batteries are collected, crushed, and the components are separated. The lead is remelted and refined to produce secondary lead of identical quality to primary lead. This process uses up to 80% less energy than mining.

Given its proven toxicity, strict international regulations have been implemented:

Remediation is complex and costly. Methods include excavation and burial of contaminated soils, stabilization/solidification (locking lead in a matrix), or phytoremediation (use of accumulator plants, such as certain ferns).

Lead illustrates the paradox of a useful but dangerous material. The goal is to:

The history of lead is a powerful warning about the need to assess the long-term impacts of technologies before their mass diffusion.