Gallium has a remarkable history because its discovery validated one of the most famous predictions of Dmitri Mendeleev (1834-1907). In 1871, Mendeleev predicted the existence of an element he named eka-aluminum, located below aluminum in his periodic table. He described its expected properties with astonishing accuracy: a density of about 5.9 g/cm³, a low melting point, and the ability to form oxides and salts.

In 1875, the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1838-1912) discovered gallium by analyzing a zinc blende from the Pyrenees using spectroscopy. He observed two new violet lines in the spectrum and succeeded in isolating a few milligrams of the new metal. The measured properties almost perfectly matched Mendeleev's predictions, providing a brilliant validation of the periodic table.

The name gallium was chosen by Lecoq de Boisbaudran in reference to the Latin name for France (Gallia), although some suggested a bilingual pun with his own name (le coq meaning gallus in Latin). Mendeleev himself congratulated Lecoq de Boisbaudran while noting slight differences with his predictions, particularly regarding density.

Gallium (symbol Ga, atomic number 31) is a poor metal in group 13 of the periodic table. Its atom has 31 protons, usually 38 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{69}\mathrm{Ga}\)) and 31 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p¹.

Gallium has exceptional physical properties that distinguish it from almost all other metals. At room temperature, it is a solid, silvery-white, shiny metal, relatively dense (density ≈ 5.91 g/cm³ in solid form). Its most remarkable feature is its extraordinarily low melting point: 29.76 °C (302.91 K), meaning it literally melts in the human hand.

Gallium exhibits a unique and spectacular property: an exceptionally wide liquid range. It remains liquid from 29.76 °C to its boiling point at 2,400 °C (2,673 K), a range of over 2,370 °C. This is one of the largest liquid ranges of all elements, comparable only to that of mercury.

Solid gallium is relatively soft and can be cut with a knife. It has an unusual orthorhombic crystal structure with only one nearest neighbor atom (at 2.43 Å), which partly explains its low melting point. Like water, gallium expands when solidifying (volume increase of about 3.1%), a rare property among metals.

Liquid gallium has the particularity of "wetting" most other metals (except iron, tungsten, and tantalum), penetrating their grain boundaries and potentially weakening them. Glass and porcelain are the preferred materials for containing liquid gallium.

The melting point (liquid state) of gallium: 302.91 K (29.76 °C).

The boiling point (gaseous state) of gallium : 2,673 K (≈ 2,400 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallium-69 — \(\,^{69}\mathrm{Ga}\,\) | 31 | 38 | 68.925574 u | ≈ 60.11 % | Stable | Dominant isotope of natural gallium. Has a nuclear magnetic moment used in NMR. |

| Gallium-71 — \(\,^{71}\mathrm{Ga}\,\) | 31 | 40 | 70.924701 u | ≈ 39.89 % | Stable | Second stable isotope. Also used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Gallium-67 — \(\,^{67}\mathrm{Ga}\,\) | 31 | 36 | 66.928202 u | Synthetic | ≈ 3.26 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Gamma emitter used in nuclear medicine for imaging infections and tumors. |

| Gallium-68 — \(\,^{68}\mathrm{Ga}\,\) | 31 | 37 | 67.927980 u | Synthetic | ≈ 67.7 minutes | Radioactive (β⁺, electron capture). Positron emitter used in PET (positron emission tomography) for medical imaging. |

| Gallium-72 — \(\,^{72}\mathrm{Ga}\,\) | 31 | 41 | 71.926367 u | Synthetic | ≈ 14.1 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Produced in nuclear reactors, used in research. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

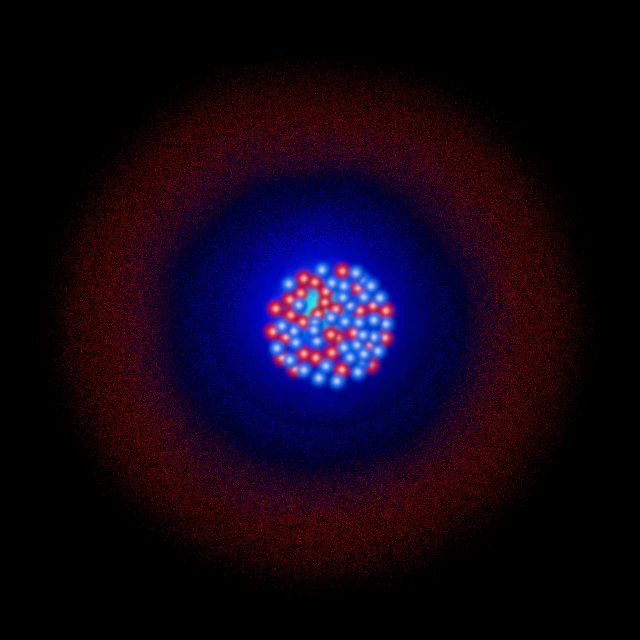

Gallium has 31 electrons distributed across four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is : 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p¹, or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p¹. This configuration can also be written : K(2) L(8) M(18) N(3).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. The presence of the complete 3d subshell is characteristic of post-transition elements and significantly influences the properties of gallium.

N Shell (n=4): contains 3 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p¹. These three electrons are the valence electrons of gallium.

The 3 electrons in the outer shell (4s² 4p¹) are the valence electrons of gallium. This configuration explains its chemical properties:

The main oxidation state of gallium is +3, where it loses its three valence electrons to form the Ga³⁺ ion with the stable configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰. This complete d-subshell configuration is particularly stable.

An oxidation state of +1 also exists, particularly in gallium(I) halides such as GaCl or GaBr, although it is less stable and easily disproportionates: 3Ga⁺ → 2Ga⁰ + Ga³⁺. The +1 state involves the loss of the single 4p¹ electron, leaving the 4s² pair intact (inert pair effect).

Oxidation states of +2 have been observed in some transient compounds, but they are rare and unstable. Metallic gallium (existing in the 0 state) occurs naturally in its elemental form.

The presence of the complete 3d¹⁰ subshell just before the valence electrons has a significant effect: it poorly shields the nuclear charge, making the 4s and 4p electrons more strongly bound to the nucleus. This is one of the reasons why the atomic radius of gallium (135 pm) is surprisingly similar to that of aluminum (143 pm) despite an additional electron shell, a phenomenon known as the lanthanide contraction (although in this case, it is due to the 3d series).

Gallium is relatively unreactive at room temperature. It quickly forms a thin layer of gallium oxide (Ga₂O₃) that protects it from further oxidation. This protective layer gives gallium reasonable resistance to atmospheric corrosion.

Gallium reacts slowly with oxygen at room temperature but oxidizes rapidly at high temperatures, forming gallium(III) oxide: 4Ga + 3O₂ → 2Ga₂O₃. This oxide is amphoteric, reacting with both acids and bases.

Gallium reacts with most non-oxidizing acids to form gallium(III) salts and release hydrogen: 2Ga + 6HCl → 2GaCl₃ + 3H₂. However, it resists concentrated nitric acid, which forms a protective oxide layer (passivation).

With strong bases, gallium reacts to form gallates: 2Ga + 2OH⁻ + 6H₂O → 2[Ga(OH)₄]⁻ + 3H₂. This reaction is similar to that of aluminum, reflecting their position in the same group of the periodic table.

Gallium reacts vigorously with halogens to form trihalides: 2Ga + 3X₂ → 2GaX₃ (where X = F, Cl, Br, I). It also reacts with sulfur, selenium, and tellurium to form gallium chalcogenides.

A remarkable property of liquid gallium is its ability to dissolve many metals, forming amalgams or liquid alloys. It can embrittle certain metals through intergranular penetration, a phenomenon called liquid metal embrittlement.

Gallium is synthesized in stars through several nucleosynthesis processes. It is mainly formed during the explosive burning of silicon during type II supernova explosions, as well as by slow neutron capture processes (s-process) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars.

The two stable isotopes of gallium (\(\,^{69}\mathrm{Ga}\) and \(\,^{71}\mathrm{Ga}\)) are produced by these mechanisms and dispersed into the interstellar medium during cataclysmic events. The isotopic ratio ⁶⁹Ga/⁷¹Ga measured in primitive meteorites provides information on the nucleosynthesis conditions in the primordial solar system.

The abundance of gallium in the universe is relatively low, about 10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This cosmic rarity reflects the difficulties in forming nuclei in this atomic mass region (A ≈ 70) during stellar nucleosynthesis.

Gallium plays a particular role in neutrino physics. The GALLEX (GALLium EXperiment), conducted in the Gran Sasso underground laboratory in Italy between 1991 and 1997, used 30 tons of metallic gallium to detect low-energy solar neutrinos via the reaction: νₑ + ⁷¹Ga → ⁷¹Ge + e⁻. This experiment contributed to the discovery of neutrino oscillation, confirming that neutrinos have mass.

The spectral lines of ionized gallium (Ga II, Ga III) are sometimes observed in the spectra of hot stars and specific stellar objects. The study of these lines helps understand the chemical enrichment of stars and the chemical evolution of galaxies.

N.B. :

Gallium is present in the Earth's crust at a concentration of about 0.0019% by mass (19 ppm), making it a relatively rare element, comparable in abundance to lead. It does not form its own ores but is always associated with other elements, mainly in aluminum (bauxite), zinc (blende), and germanium ores.

Gallium is primarily extracted as a byproduct of bauxite processing to produce aluminum, where it concentrates in Bayer liquors. Another important source is the treatment of zinc furnace dust. Global primary gallium production is about 450 tons per year, mainly in China (≈ 80%), Germany, Kazakhstan, and South Korea.

The recycling of gallium is becoming increasingly important with the growth of electronic waste. Gallium can be recovered from old integrated circuits, LEDs, and photovoltaic cells, although the recycling processes are still costly and not widespread. The current recycling rate is estimated at less than 1% of total production.

The demand for gallium is growing rapidly (about 10% per year) due to the expansion of the LED market, 5G devices, and electric vehicles. This growth raises questions about long-term supply security, especially since gallium is considered a critical material by the European Union and the United States due to its strategic importance and the geographical concentration of its production.