Gadolinium is synthesized in stars through two main processes: the s-process (slow neutron capture) in low-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch) and the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during cataclysmic events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. Unlike europium, gadolinium shows a significant contribution from the s-process, estimated at about 40-60% of its solar abundance, with the rest coming from the r-process.

The cosmic abundance of gadolinium is about 1.2×10⁻¹² times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about three times more abundant than europium. Its mixed production (s and r) makes it a useful tracer for studying the balance between the two nucleosynthesis processes in the galactic chemical evolution. The gadolinium/europium (Gd/Eu) ratio in stars is often used as an indicator of the relative contribution of the s-process compared to the r-process.

The abundances of gadolinium in stars of different metallicities help trace the history of chemical enrichment in the Galaxy. Very old, metal-poor stars show a relatively low Gd/Eu ratio, indicating an initial dominance of the r-process. As the Galaxy ages and AGB stars contribute more, the Gd/Eu ratio increases, reflecting the growing contribution of the s-process. This evolution is a key indicator of the history of star formation and nucleosynthesis in the Milky Way.

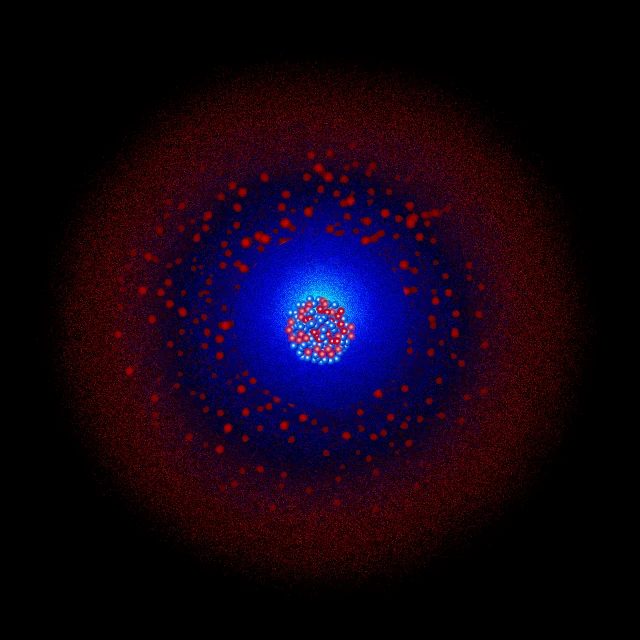

Gadolinium has been detected in the atmospheres of certain peculiar stars, particularly Ap-type stars (magnetic pole stars) where it can be overabundant relative to iron by up to a factor of 1000. In these stars, the strong magnetic field and weak convection allow the diffusive separation of elements, leading to atmospheric stratification where gadolinium accumulates. The analysis of spectral lines of neutral (Gd I) and ionized (Gd II) gadolinium in these stars provides important constraints on models of diffusion and stellar magnetic fields.

Gadolinium is named after the Finnish chemist Johan Gadolin (1760-1852), a pioneer in rare earth chemistry who discovered yttrium in 1794. The name honors his fundamental contributions to the study of minerals containing rare earths. The element itself was isolated long after his death, but his name perpetuates his scientific legacy.

Gadolinium was discovered in 1880 by the Swiss chemist Jean-Charles Galissard de Marignac (1817-1894) in Geneva. By analyzing samples of didymium (then believed to be a single element, but later found to be a mixture of neodymium and praseodymium) and cerite, Marignac observed unknown spectral lines. He isolated a new oxide which he initially named "Yα", demonstrating that it was the oxide of a new element. Marignac was an expert in crystallography and spectroscopy, techniques crucial for this discovery.

In 1886, the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran (known for discovering gallium) confirmed the existence of the new element and proposed the name "gadolinium" in honor of Johan Gadolin. Lecoq de Boisbaudran succeeded in separating gadolinium from other rare earths with greater purity and determined some of its fundamental properties. The isolation of pure metallic gadolinium was achieved much later, in 1935, by reducing anhydrous gadolinium chloride with metallic calcium.

Gadolinium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 6.2 ppm (parts per million), making it the 41st most abundant element, slightly more abundant than boron or nitrogen. Among the rare earths, it is of average abundance. The main ores containing gadolinium are bastnasite ((Ce,La,Nd,Gd)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Gd,Th)PO₄), where it typically represents 0.5 to 1.5% of the total rare earth content.

Global production of gadolinium oxides is about 400 to 500 tons per year. China dominates production with about 85% of the world total, followed by the United States, Australia, and Malaysia. The price of gadolinium varies considerably depending on purity and demand, with 99.9% gadolinium oxide (Gd₂O₃) typically trading between $50 and $150 per kilogram.

Metallic gadolinium is mainly produced by reducing Gd₂O₃ or GdF₃ with metallic calcium in an inert atmosphere. Global annual production of metallic gadolinium is about 50 to 100 tons. Recycling of gadolinium from magnets and electronic waste is still limited but is gaining importance for economic and strategic reasons, with recovery rates that could increase significantly in the coming decades.

Gadolinium (symbol Gd, atomic number 64) is the eighth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the rare earths of the f-block of the periodic table. Its atom has 64 protons, usually 94 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{158}\mathrm{Gd}\)) and 64 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁷ 5d¹ 6s². This half-filled 4f⁷ configuration gives gadolinium exceptional magnetic properties.

Gadolinium is a silvery, malleable, and ductile metal. Its most remarkable property is its ferromagnetism at room temperature among the lanthanides. Gadolinium becomes ferromagnetic below its Curie temperature of 20 °C (293 K). Above this temperature, it is paramagnetic. It is one of the few elements (along with iron, nickel, and cobalt) to exhibit ferromagnetic behavior at room temperature. Gadolinium also has the highest thermal neutron absorption cross-section of all stable elements (49,000 barns).

Gadolinium melts at 1313 °C (1586 K) and boils at 3273 °C (3546 K), with high melting and boiling points typical of lanthanides. Gadolinium crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure at room temperature. It exhibits a thermal expansion anomaly: it contracts when heated to about 200 °C before expanding normally. Gadolinium is a poor electrical conductor, with conductivity about 20 times lower than that of copper.

Gadolinium is moderately reactive. It oxidizes slowly in dry air to form black Gd₂O₃. In humid air or when heated, oxidation accelerates. Gadolinium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form gadolinium(III) hydroxide Gd(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves in dilute mineral acids with hydrogen release. Metallic gadolinium must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere to prevent gradual oxidation.

Melting point of gadolinium: 1586 K (1313 °C).

Boiling point of gadolinium: 3546 K (3273 °C).

Curie temperature of gadolinium: 293 K (20 °C) - ferromagnetic below.

Thermal neutron absorption cross-section: 49,000 barns (highest among stable elements).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gadolinium-154 — \(\,^{154}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 90 | 153.920865 u | ≈ 2.18 % | Stable | Stable isotope but slightly radioactive with an extremely long half-life (> 1.1×10²¹ years). |

| Gadolinium-155 — \(\,^{155}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 91 | 154.922622 u | ≈ 14.80 % | Stable | Stable isotope with the highest neutron absorption cross-section among natural isotopes. |

| Gadolinium-156 — \(\,^{156}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 92 | 155.922122 u | ≈ 20.47 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope of natural gadolinium. |

| Gadolinium-157 — \(\,^{157}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 93 | 156.923960 u | ≈ 15.65 % | Stable | Stable isotope with an extremely high neutron absorption cross-section (254,000 barns). |

| Gadolinium-158 — \(\,^{158}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 94 | 157.924103 u | ≈ 24.84 % | Stable | Major stable isotope, representing about a quarter of natural gadolinium. |

| Gadolinium-160 — \(\,^{160}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 96 | 159.927054 u | ≈ 21.86 % | Stable | Stable isotope, the heaviest of the natural gadolinium isotopes. |

| Gadolinium-152 — \(\,^{152}\mathrm{Gd}\,\) | 64 | 88 | 151.919791 u | ≈ 0.20 % | 1.08×10¹⁴ years | Alpha radioactive with extremely long half-life. Present in trace amounts in nature. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Gadolinium has 64 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁷ 5d¹ 6s² is unique because it has a half-filled 4f subshell (7 electrons) and one electron in the 5d subshell, which gives it particular stability according to Hund's rule. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(25) P(3), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f⁷ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration.

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 25 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f⁷ 5d¹. The half-filled 4f subshell and the presence of a 5d electron characterize the chemistry and magnetism of gadolinium.

P shell (n=6): contains 3 electrons in the 6s² and 5d¹ subshells (although 5d belongs to the n=5 shell, it is energetically close to 6s).

Gadolinium effectively has 10 valence electrons: seven 4f⁷ electrons, two 6s² electrons, and one 5d¹ electron. However, in chemical practice, gadolinium almost exclusively exhibits the +3 oxidation state. In this state, gadolinium loses its two 6s electrons, its 5d electron, and one 4f electron to form the Gd³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁷. This ion has exactly seven electrons in the 4f subshell (half-filled), giving it exceptional stability and remarkable magnetic properties.

Unlike europium and ytterbium, gadolinium does not have a stable +2 oxidation state under ordinary aqueous conditions. A few gadolinium(II) compounds exist, such as GdI₂, but they are highly reducing and quickly oxidize in the presence of moisture or oxygen. The +3 state is so stable that gadolinium is considered the most "earth-like" lanthanide in its chemical behavior.

The Gd³⁺ ion has several important physical properties: it is paramagnetic with seven unpaired electrons (magnetic moment of 7.94 μB), has an ionic radius of 107.8 pm (for coordination number 8), and has weak luminescence compared to other lanthanides such as europium or terbium, but it is used in some phosphorescent materials.

Gadolinium metal oxidizes slowly in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin layer of white gadolinium(III) oxide Gd₂O₃ that adheres to the metal and partially protects it from further oxidation. When heated above 200 °C, oxidation accelerates and the metal can ignite in air, burning to form the oxide: 4Gd + 3O₂ → 2Gd₂O₃. In fine powder form, gadolinium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Gadolinium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form gadolinium(III) hydroxide Gd(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Gd + 6H₂O → 2Gd(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous white solid with low solubility. The reaction is not as vigorous as with alkali metals or even some other lanthanides such as europium, but it is notable and requires precautions when storing the metal.

Gadolinium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides: 2Gd + 3F₂ → 2GdF₃ (white fluoride); 2Gd + 3Cl₂ → 2GdCl₃ (white chloride). It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) with hydrogen release and formation of the corresponding Gd³⁺ salts: 2Gd + 6HCl → 2GdCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Gadolinium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperatures (300-400 °C) to form GdH₂, then GdH₃ at higher temperatures. With sulfur, it forms Gd₂S₃. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperature (>1000 °C) to form GdN, and with carbon to form GdC₂. Gadolinium also forms many coordination complexes with organic ligands, exploited in particular in MRI contrast agents.

The most remarkable property of gadolinium is its ferromagnetism near room temperature. With a Curie temperature of 20 °C (293 K), gadolinium is ferromagnetic below this temperature and paramagnetic above. This effect is due to the seven unpaired electrons in the 4f subshell of the Gd³⁺ ion, which generate a strong magnetic moment. Gadolinium also exhibits a giant magnetocaloric effect, meaning its temperature changes significantly when subjected to a magnetic field. This property is exploited in magnetic refrigeration, an energy-efficient cooling technology.

The most important application of gadolinium is its use in contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Gd³⁺ ions have seven unpaired electrons, giving them a strong magnetic moment and an exceptional ability to reduce the T1 relaxation time of water protons in biological tissues. When injected into the body, gadolinium complexes accelerate the alignment of water proton spins after the radiofrequency pulse, producing a stronger MRI signal (brighter image) in regions where they accumulate.

Free gadolinium (Gd³⁺) is toxic and must therefore be chelated (bound to an organic molecule) for safe use in humans. The most common chelates are DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid), DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) and their derivatives. These molecules tightly enclose the Gd³⁺ ion, preventing its release into the body and allowing rapid renal elimination. Millions of injections are performed each year worldwide with a generally excellent safety profile.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents are essential for detecting and characterizing many pathologies: brain tumors and other cancers, inflammations, spinal cord lesions, vascular diseases (MRI angiography), cardiac pathologies, and demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis. They allow visualization of tumor vascularization, detection of blood-brain barrier disruptions, and improved detection of small lesions. Different agents are designed for specific tissue distributions (hepatic, renal, etc.).

Gadolinium exhibits a "giant magnetocaloric effect" near its Curie temperature (20 °C). When a magnetic field is applied to a magnetocaloric material such as gadolinium, the magnetic moments align, reducing the magnetic entropy of the system. To maintain total entropy (and comply with the laws of thermodynamics), the entropy of the crystal lattice increases, resulting in a temperature increase. When the field is removed, the reverse process occurs and the material cools.

Magnetic refrigeration using gadolinium or its alloys offers considerable potential advantages: no ozone-depleting or high global warming potential refrigerants, potentially 20 to 30% higher energy efficiency than traditional compressors, quieter operation, and simplified mechanical design. Prototypes often use beds of gadolinium or Gd-Si-Ge alloy pellets. Current research aims to develop less expensive and more effective gadolinium-based magnetocaloric materials over a wider temperature range.

Targeted applications include domestic and automotive air conditioning, commercial refrigeration, cryogenics (very low temperature cooling in cascade with other materials), and high-performance electronic cooling. Although commercially limited at present due to the cost of gadolinium and technical challenges, this technology represents a promising path for sustainable cooling.

Gadolinium has the highest thermal neutron absorption cross-section of all stable elements (49,000 barns on average for the natural isotopic mixture, with peaks at 254,000 barns for the Gd-157 isotope). This property makes it a material of choice for neutron control and protection in the nuclear industry.

In nuclear reactors, gadolinium is used in oxide form (Gd₂O₃) mixed with fuel (uranium or plutonium) as a "burnable poison" to compensate for excess reactivity at the beginning of the cycle. By absorbing neutrons, it controls the chain reaction. As the reactor operates, the gadolinium is "burned" (transmuted into other elements), allowing increased reactivity that compensates for fuel depletion. It is also used in certain control rods and shielding.

Gadolinium compounds (oxides, fluorides) are used in neutron detectors and converters for neutron imaging. When a neutron is absorbed by a gadolinium nucleus, it triggers the emission of detectable gamma rays or charged particles. Gadolinium screens allow the conversion of a neutron flux into a visible image, a technique used in research, non-destructive testing, and security (detection of nuclear materials).

Free (unchelated) gadolinium salts are moderately toxic. Injection of free Gd³⁺ can cause severe hypocalcemia (related to competition with calcium), nausea, vomiting, and at high doses, cardiac disorders and death. The toxicity mechanism mainly involves the blocking of calcium channels. The LD50 (median lethal dose) of gadolinium chloride in rats is about 100-200 mg/kg intravenously. Fortunately, MRI contrast agents use very stable chelated complexes that minimize the release of free Gd³⁺.

A major concern associated with gadolinium-based contrast agents is nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a rare but serious and sometimes fatal disease that affects patients with severe renal failure. NSF is characterized by thickening and hardening of the skin and internal organs. It is linked to the release of free gadolinium from certain less stable chelates (linear vs. macrocyclic) in patients whose renal excretion mechanisms are compromised. This discovery has led to usage restrictions and a preference for more stable macrocyclic agents in at-risk patients.

Recent studies have shown that small amounts of gadolinium can be retained long-term in the brain and other tissues (bone, skin) even in patients with normal renal function, particularly with linear agents. The long-term clinical implications of this retention are still uncertain and are the subject of active research. No clear negative consequences have been demonstrated to date, but as a precaution, regulatory authorities recommend using the lowest effective dose and preferring more stable agents.

Environmental concerns mainly relate to the mining of rare earths, common to all these elements. Gadolinium released into the environment via medical effluents (patient urine after MRI) is under study, although the amounts are small and the forms generally chelated. Recycling of gadolinium from electronic waste and used magnets is an increasing economic and strategic issue to secure supply and reduce the environmental impact of primary extraction. Hydrometallurgical processes allow gadolinium to be recovered with high yields.

To minimize risks, medical practices have evolved: assessment of renal function before injection (creatinine clearance), preferential use of stable macrocyclic agents, strict adherence to contraindications in patients at risk of NSF, and careful justification of each examination requiring contrast. Research continues to develop new, even more stable, biodegradable agents, or agents specifically targeting certain pathologies, in order to maximize diagnostic benefit while minimizing potential risks.