Manganese gets its name from black magnesia, a manganese oxide ore known since antiquity for its ability to decolorize glass or give it a purple tint. In 1774, the Swedish chemist Johan Gottlieb Gahn (1745-1818) isolated metallic manganese for the first time by reducing manganese dioxide with carbon. This discovery followed the work of Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742-1786), who had demonstrated a few years earlier that pyrolusite contained a new element. Scheele had identified this element in 1774, but it was Gahn who succeeded in isolating it in metallic form the same year. The name "manganese" comes from the Latin magnes, referring to the magnetic properties of some of its compounds, although the pure metal is not magnetic.

Manganese (symbol Mn, atomic number 25) is a transition metal in group 7 of the periodic table. Its atom has 25 protons, usually 30 neutrons (for the stable isotope \(\,^{55}\mathrm{Mn}\)), and 25 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s².

At room temperature, manganese is a solid, silvery-gray metal, relatively hard and brittle (density ≈ 7.21 g/cm³). It exists in several allotropic forms, with the alpha form being the most stable at ordinary temperatures. Manganese oxidizes slowly in air and dissolves easily in dilute acids. The melting point of manganese (liquid state): 1,519 K (1,246 °C). The boiling point of manganese (gaseous state): 2,334 K (2,061 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manganese-55 — \(\,^{55}\mathrm{Mn}\,\) | 25 | 30 | 54.938044 u | 100 % | Stable | Only stable isotope of manganese, present throughout nature. |

| Manganese-53 — \(\,^{53}\mathrm{Mn}\,\) | 25 | 28 | 52.941290 u | Cosmogenic trace | ≈ 3.7 million years | Radioactive, electron capture to \(\,^{53}\mathrm{Cr}\). Used to date oceanic manganese nodules. |

| Manganese-54 — \(\,^{54}\mathrm{Mn}\,\) | 25 | 29 | 53.940359 u | Artificial | ≈ 312.2 days | Radioactive, electron capture to \(\,^{54}\mathrm{Cr}\). Produced in nuclear reactors, used as a tracer. |

| Manganese-52 — \(\,^{52}\mathrm{Mn}\,\) | 25 | 27 | 51.945565 u | Artificial | ≈ 5.6 days | Radioactive, positron emitter. Used in PET medical imaging. |

| Manganese-56 — \(\,^{56}\mathrm{Mn}\,\) | 25 | 31 | 55.938905 u | Artificial | ≈ 2.6 hours | Radioactive, beta-minus decay to \(\,^{56}\mathrm{Fe}\). Produced by neutron activation. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

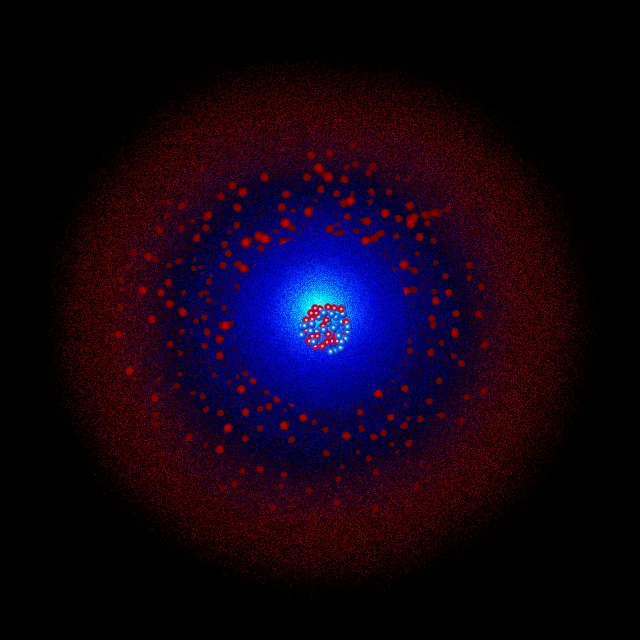

Manganese has 25 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁵ 4s², or simplified: [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(13) N(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 13 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁵. The 3s and 3p orbitals are complete, while the 3d orbitals are half-filled with 5 electrons, a particularly stable configuration.

N shell (n=4): contains 2 electrons in the 4s subshell. These electrons are the first to be involved in chemical bonding.

The 7 electrons in the outer shells (3d⁵ 4s²) constitute the valence electrons of manganese. This configuration explains its varied chemical properties:

Manganese can adopt many oxidation states, from +2 to +7, making it one of the most versatile elements.

The +2 oxidation state (Mn²⁺) is the most common and stable in aqueous solution.

The +4 state is present in manganese dioxide (MnO₂), a very important industrial compound.

The +7 state exists in permanganate (MnO₄⁻), a powerful oxidizing agent with an intense purple color.

The half-filled 3d⁵ configuration gives particular stability to the Mn²⁺ ion. This electronic structure also explains why manganese forms compounds with varied colors depending on its oxidation state: pale pink for Mn²⁺, dark brown for MnO₂, green for Mn⁶⁺, purple for MnO₄⁻.

Manganese is a moderately reactive metal. It oxidizes slowly in humid air and more rapidly at high temperatures, forming various oxides. It reacts with hot water to release hydrogen and dissolves easily in dilute acids, producing dihydrogen. Manganese can react with halogens, sulfur, nitrogen, and carbon at high temperatures. Its compounds exhibit a wide variety of oxidation states, from +2 to +7, making it a chemically very versatile element. Manganese dioxide (MnO₂) acts as a catalyst in many reactions, including the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. Potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) is a powerful oxidant widely used in analytical chemistry and water treatment.

Manganese is an essential trace element for all living organisms. It plays a crucial role as an enzymatic cofactor in many biochemical reactions. In plants, manganese is essential for photosynthesis, directly participating in the photolysis of water in photosystem II. In animals and humans, it is necessary for the metabolism of carbohydrates, amino acids, and cholesterol. Manganese activates several important enzymes, including mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2), which protects cells from oxidative damage. It also participates in bone formation, blood clotting, and the functioning of the nervous system. A manganese deficiency can lead to growth disorders, bone abnormalities, and reproductive problems, although such deficiencies are rare in humans.

Manganese is produced mainly during explosive nucleosynthesis that occurs during type Ia supernovae and core-collapse supernovae. It forms through neutron capture and nuclear reactions involving iron and chromium in the outer layers of the exploding star. The radioactive isotope \(\,^{53}\mathrm{Mn}\) (half-life of 3.7 million years) is particularly interesting because it allows the study of chemical enrichment processes in the early solar system. Its presence in ancient meteorites provides information on the timing of the formation of the first solid bodies in the solar system.

The spectral lines of manganese (Mn I, Mn II) are used in stellar spectroscopy to determine the chemical composition of stars and trace the chemical evolution of galaxies. The manganese/iron ratio in ancient stars helps astronomers understand the relative contributions of different types of supernovae to the chemical enrichment of the Universe. Manganese nodules discovered on the terrestrial ocean floor also contain cosmogenic \(\,^{53}\mathrm{Mn}\), allowing them to be dated and geological processes to be studied over long timescales.

N.B.:

Manganese is the twelfth most abundant element in the Earth's crust (about 0.1% by mass). It is mainly found in ores such as pyrolusite (MnO₂), rhodochrosite (MnCO₃), and braunite (Mn₂O₃). The largest deposits are located in South Africa, Australia, China, and Gabon. Polymetallic nodules on the ocean floor also contain significant amounts of manganese and represent a potential resource for the future. The extraction and processing of manganese are relatively simple compared to other metals, explaining its massive use in the global steel industry.