The history of strontium begins in 1787 in the village of Strontian, located in the Scottish Highlands. Miners discovered an unusual mineral in the local lead mines. This mineral, which looked different from other known carbonates, caught the attention of British chemists. The Irish physician and chemist Adair Crawford (1748-1795) and the Scottish chemist William Cruickshank analyzed this mineral in 1790 and recognized that it contained a new earth (metallic oxide) distinct from baryte and lime.

The mineral was named strontianite after the village of Strontian, and the new earth was called strontian. However, the isolation of metallic strontium was only achieved much later. In 1808, the British chemist Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829), a pioneer in electrochemistry, succeeded in isolating strontium by electrolysis of a moist mixture of strontium oxide and mercury oxide, using a technique similar to the one he had developed to isolate sodium, potassium, calcium, and barium.

The discovery of strontium occurred during a period of intense activity in chemistry, where spectral analysis and electrochemical methods allowed the identification and isolation of new elements. Davy isolated metallic strontium in the form of an amalgam with mercury, then obtained the pure metal by distilling the mercury. The name strontium was definitively adopted in reference to the Scottish village where the ore was discovered.

In 1852, the Scottish chemist Thomas Anderson discovered another important mineral form of strontium, celestine (or celestite), a sky-blue strontium sulfate (SrSO₄), which later became the main industrial source of strontium. This discovery enabled the commercial exploitation of strontium for various industrial applications.

Strontium (symbol Sr, atomic number 38) is an alkaline earth metal in group 2 of the periodic table. Its atom has 38 protons, usually 50 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{88}\mathrm{Sr}\)) and 38 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 5s².

Strontium is a soft, silvery-white, and shiny metal when freshly cut. It has a density of 2.64 g/cm³, intermediate between that of calcium (1.55 g/cm³) and barium (3.51 g/cm³), reflecting its position in group 2. Strontium is soft enough to be cut with a knife, although it is slightly harder than calcium.

Strontium crystallizes in a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure at room temperature. At about 215 °C, it undergoes a phase transformation to a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure. This phase transition affects some of its physical properties such as electrical and thermal conductivity.

Strontium melts at 777 °C (1050 K) and boils at 1382 °C (1655 K). In the open air, metallic strontium quickly tarnishes, forming a yellowish layer of oxide and nitride. This protective layer slows down further oxidation but does not prevent the gradual corrosion of the metal. For this reason, metallic strontium must be stored in mineral oil or under an inert argon atmosphere.

Melting point of strontium: 1050 K (777 °C).

Boiling point of strontium: 1655 K (1382 °C).

Strontium has an electrical conductivity of about 7.9% that of copper.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strontium-84 — \(\,^{84}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 46 | 83.913425 u | ≈ 0.56% | Stable | Lightest and rarest stable isotope of natural strontium. |

| Strontium-86 — \(\,^{86}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 48 | 85.909260 u | ≈ 9.86% | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope, used as a tracer in geochemistry. |

| Strontium-87 — \(\,^{87}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 49 | 86.908877 u | ≈ 7.00% | Stable | Radiogenic isotope produced by the decay of rubidium-87. Used in Rb-Sr dating and geological tracing. |

| Strontium-88 — \(\,^{88}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 50 | 87.905612 u | ≈ 82.58% | Stable | By far the most abundant isotope of natural strontium, representing more than 4/5 of the total. |

| Strontium-89 — \(\,^{89}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 51 | 88.907451 u | Synthetic | ≈ 50.6 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Nuclear fission product. Used in nuclear medicine to treat painful bone metastases. |

| Strontium-90 — \(\,^{90}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 52 | 89.907474 u | Synthetic | ≈ 28.8 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Major fission product, very dangerous as it accumulates in bones. Important radiological contaminant. |

| Strontium-85 — \(\,^{85}\mathrm{Sr}\,\) | 38 | 47 | 84.912933 u | Synthetic | ≈ 64.8 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Gamma emitter used as a tracer in medicine and hydrology. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Strontium has 38 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 5s², or simplified: [Kr] 5s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(8) O(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic shielding protecting the valence electrons.

N shell (n=4): contains 8 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶, forming the krypton noble gas configuration.

O shell (n=5): contains 2 electrons in the 5s subshell. These two electrons are the valence electrons of strontium.

The 2 electrons in the outer shell (5s²) are the valence electrons of strontium. These electrons are relatively weakly bound to the nucleus due to the significant distance separating them from the nucleus and the shielding effect of the complete inner electron shells. This low ionization energy gives strontium a high chemical reactivity, characteristic of alkaline earth metals.

The oxidation state of strontium is exclusively +2 in all its stable chemical compounds. Strontium easily loses its two valence electrons to form the Sr²⁺ ion with the stable electronic configuration of krypton [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶. This complete octet configuration with 36 electrons makes the strontium ion particularly stable.

The ionic radius of Sr²⁺ (118 pm) is significantly larger than that of calcium Ca²⁺ (100 pm) and smaller than that of barium Ba²⁺ (135 pm), reflecting its intermediate position in group 2. This intermediate size has important consequences in biochemistry and geochemistry, as the strontium ion can substitute for the calcium ion in many crystalline structures and biological processes.

The moderate electronegativity of strontium (0.95 on the Pauling scale) indicates that its chemical bonds are primarily ionic. Strontium forms ionic compounds with almost all nonmetals, including halogens, oxygen, sulfur, and anionic groups such as carbonates, sulfates, and nitrates. The pronounced metallic character of strontium classifies it among the most electropositive elements.

Strontium is a highly reactive metal, although slightly less so than calcium. It reacts vigorously with water at room temperature, producing strontium hydroxide and hydrogen gas: Sr + 2H₂O → Sr(OH)₂ + H₂. The reaction is exothermic and produces enough heat to ignite the released hydrogen, creating a characteristic crimson flame due to vaporized strontium.

In air, strontium oxidizes rapidly, first forming a layer of strontium oxide (SrO), then strontium nitride (Sr₃N₂) in the presence of atmospheric nitrogen: 2Sr + O₂ → 2SrO and 3Sr + N₂ → Sr₃N₂. The surface of the metal changes from shiny silvery-white to dull yellow in a few minutes. At high temperatures (above 300 °C), strontium burns in air with a characteristic bright red flame.

With halogens, strontium reacts energetically to form strontium halides: Sr + Cl₂ → SrCl₂. Strontium halides (SrF₂, SrCl₂, SrBr₂, SrI₂) are white ionic solids, very stable and hygroscopic. Strontium chloride (SrCl₂) is particularly used in pyrotechnics to produce intense red flames.

Strontium reacts with acids, even diluted, to form strontium salts and release hydrogen: Sr + 2HCl → SrCl₂ + H₂. With dilute sulfuric acid, the reaction slows down rapidly because the formed strontium sulfate (SrSO₄) is poorly soluble and covers the metal with a protective layer.

Strontium reacts directly with hydrogen at high temperature (about 200-500 °C) to form strontium hydride (SrH₂), a gray ionic compound used as a hydrogen source and reducing agent. With carbon at high temperature, it forms strontium carbide (SrC₂), which reacts with water to produce acetylene.

Strontium forms important compounds with oxygen: the oxide SrO, the peroxide SrO₂, and the superoxide Sr(O₂)₂. Strontium hydroxide Sr(OH)₂ is a strong soluble base, forming caustic alkaline solutions. Strontium carbonate (SrCO₃), naturally present in strontianite, is poorly soluble in water and decomposes at high temperature to give the oxide.

Strontium-90 is one of the most dangerous fission products from nuclear reactions and atomic bomb explosions. With a half-life of 28.8 years, it remains radioactive for several centuries (about 10 half-lives, or nearly 300 years). Strontium-90 is formed during the fission of uranium-235 and plutonium-239 with a fission yield of about 5 to 6%.

The particular danger of strontium-90 comes from its chemical similarity to calcium. When ingested or inhaled, strontium-90 concentrates in bones and teeth, where it substitutes for calcium in hydroxyapatite. Once incorporated into the skeleton, it remains there for many years, continuously irradiating bone tissues and bone marrow with beta rays. This chronic irradiation significantly increases the risk of bone cancer, leukemia, and other hematological disorders.

The main sources of strontium-90 contamination in the environment were atmospheric nuclear tests conducted between 1945 and 1980, which dispersed significant amounts of strontium-90 into the global atmosphere. Radioactive fallout settled on agricultural soils, contaminating crops and entering the food chain, particularly through dairy products.

Major nuclear accidents such as those at Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011) also released significant amounts of strontium-90 into the environment. At Chernobyl, it is estimated that about 10% of the reactor's strontium-90 inventory was released, creating persistent contamination zones within a radius of several tens of kilometers around the site.

Environmental monitoring of strontium-90 remains an important public health issue. Levels in the environment have significantly decreased since the end of atmospheric testing, but strontium-90 continues to be detectable in soils, sediments, and certain food products, particularly in regions affected by historical fallout or nuclear accidents.

Strontium is synthesized in stars through several stellar nucleosynthesis processes. The stable isotopes of strontium (\(\,^{84}\mathrm{Sr}\), \(\,^{86}\mathrm{Sr}\), \(\,^{87}\mathrm{Sr}\), \(\,^{88}\mathrm{Sr}\)) are mainly produced by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers.

The isotope strontium-87 holds a special position as it is both primordial (formed by stellar nucleosynthesis) and radiogenic (produced by the decay of rubidium-87). The isotopic ratio ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr in rocks and meteorites increases over time due to the accumulation of radiogenic strontium-87. This ratio is a fundamental geochronological and geochemical tool.

The cosmic abundance of strontium is about 2.3×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This relatively modest abundance reflects its position beyond the iron peak in the nuclear stability curve, where nucleosynthesis processes become less efficient.

The isotopic ratio ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr is used to trace the origin and evolution of materials in the solar system. Primitive meteorites such as chondrites exhibit homogeneous initial ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr ratios of about 0.699, representing the composition of the early solar system. The variations observed in different terrestrial rocks and meteorites allow the reconstruction of the thermal and geochemical history of planetary bodies.

The spectral lines of neutral strontium (Sr I) and ionized strontium (Sr II) are particularly important in spectroscopic astrophysics. The Sr II line at 407.8 nm is a strong resonance line, easily observable in stellar spectra. The analysis of this line and other strontium lines allows the determination of strontium abundance in stars of different types and ages, thus tracing the chemical enrichment of galaxies.

Significant excesses of strontium have been observed in certain chemically peculiar stars, particularly barium stars and carbon stars, which have been enriched in s-process elements by mass transfer from an AGB companion star. These observations confirm our understanding of nucleosynthesis and stellar evolution in binary systems.

N.B. :

Strontium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.036% by mass (360 ppm), making it the 15th most abundant element in the crust. It is more abundant than carbon, sulfur, or chlorine. Strontium is never found in its native state but always combined in minerals.

The two main strontium ores are celestine or celestite (strontium sulfate, SrSO₄) and strontianite (strontium carbonate, SrCO₃). Celestine, by far the most abundant and the main commercial source, occurs as sky-blue to colorless crystals. The main celestine deposits are found in Spain, Mexico, Turkey, Iran, and Argentina.

Global production of strontium compounds (mainly as carbonate and nitrate) is about 350,000 tons per year. Spain, China, Mexico, and Argentina are the main producers. Pure metallic strontium is produced in much smaller quantities, mainly by reduction of strontium oxide with aluminum at high temperature in a vacuum.

The strontium market has evolved significantly over the past decades. Demand for television cathode ray tubes, once the main application, has virtually disappeared with the advent of flat screens. Today, demand is dominated by ferrite magnets, fireworks, and specialized applications in ceramics and metallurgy. The price of strontium carbonate ranges between 300 and 800 euros per ton depending on purity and market conditions.

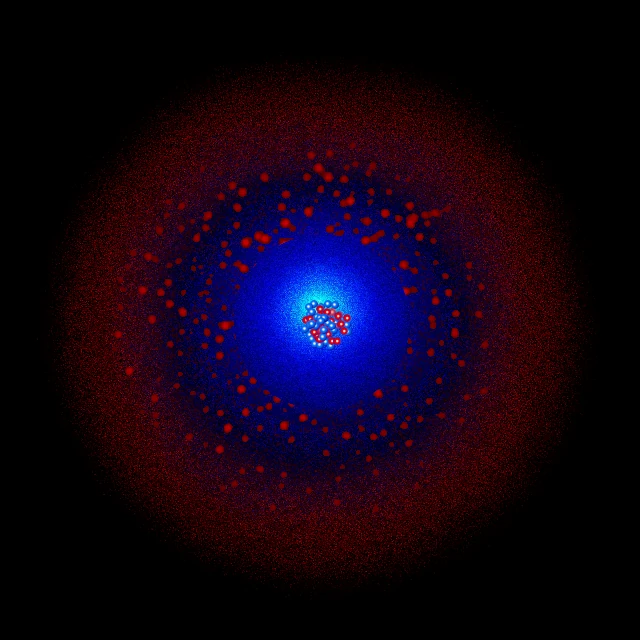

Strontium plays an increasing role in precision quantum technologies. Strontium optical atomic clocks, developed since the 2000s, are among the most precise time-measuring devices ever created. These clocks, which exploit ultra-narrow electronic transitions in laser-cooled strontium atoms, achieve a precision on the order of 10⁻¹⁸, losing or gaining only one second every 15 billion years (longer than the age of the universe). These devices could revolutionize time metrology and enable new applications in geodesy, navigation, and fundamental physics tests.