Metallic zinc was used long before its official recognition as a distinct element. Brass alloys (copper and zinc) were made as early as Antiquity, although artisans did not realize they were working with a specific metal. In India, the production of pure metallic zinc is attested from the 12th century, particularly in the Rajasthan region, where a sophisticated distillation process was used. In Europe, the German metallurgist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (1709-1782) is generally credited with the scientific discovery of zinc in 1746, when he succeeded in isolating the metal by heating calamine (zinc carbonate) with charcoal. The name zinc may come from the German Zinke (point, tooth), referring to the pointed appearance of zinc crystals, or from the Persian sing (stone).

Zinc (symbol Zn, atomic number 30) is a transition metal in group 12 of the periodic table. Its atom has 30 protons, usually 34 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{64}\mathrm{Zn}\)) and 30 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s².

At room temperature, zinc is a solid, bluish-white, shiny metal, moderately dense (density ≈ 7.14 g/cm³). It is relatively brittle at room temperature but becomes malleable and ductile between 100 and 150 °C, allowing it to be rolled and shaped. Zinc has excellent resistance to atmospheric corrosion due to the formation of a protective layer of zinc oxide and carbonate on its surface. Melting point of zinc (liquid state): 692.68 K (419.53 °C). Boiling point of zinc (gaseous state): 1,180 K (907 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc-64 — \(\,^{64}\mathrm{Zn}\,\) | 30 | 34 | 63.929142 u | ≈ 49.17 % | Stable | Dominant isotope of natural zinc. |

| Zinc-66 — \(\,^{66}\mathrm{Zn}\,\) | 30 | 36 | 65.926034 u | ≈ 27.73 % | Stable | Second most abundant stable isotope. |

| Zinc-68 — \(\,^{68}\mathrm{Zn}\,\) | 30 | 38 | 67.924844 u | ≈ 18.45 % | Stable | Third stable isotope of zinc. |

| Zinc-67 — \(\,^{67}\mathrm{Zn}\,\) | 30 | 37 | 66.927127 u | ≈ 4.04 % | Stable | Has a nuclear magnetic moment; used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Zinc-70 — \(\,^{70}\mathrm{Zn}\,\) | 30 | 40 | 69.925319 u | ≈ 0.61 % | Stable | Rarest and heaviest stable isotope of natural zinc. |

| Zinc-65 — \(\,^{65}\mathrm{Zn}\,\) | 30 | 35 | 64.929241 u | Synthetic | ≈ 244 days | Radioactive, used as a tracer in biology and medicine to study zinc metabolism. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

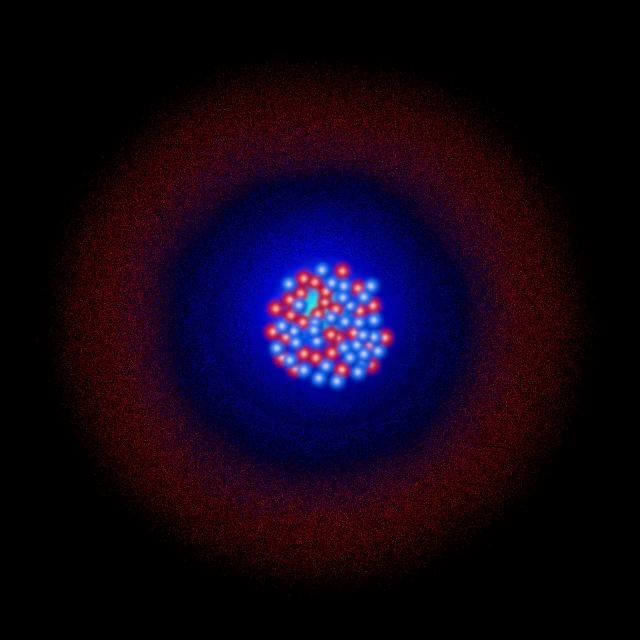

Zinc has 30 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s², or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. All orbitals in this shell are complete, giving zinc great electronic stability.

N shell (n=4): contains 2 electrons in the 4s subshell. These two electrons are the valence electrons of zinc.

The 2 electrons in the outer 4s² shell are the valence electrons of zinc. This configuration explains its chemical properties:

Zinc easily loses its two 4s electrons to form the Zn²⁺ ion (oxidation state +2), the almost exclusive oxidation state of zinc in chemistry.

The resulting configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ is particularly stable with a completely filled 3d subshell, which explains why zinc almost always forms compounds with a +2 oxidation state.

+1 oxidation states exist in rare organometallic compounds, but the +2 state dominates zinc chemistry.

Zinc's electronic configuration, with its complete 3d subshell and two 4s electrons, places it on the border between transition metals and post-transition metals. Some chemists do not consider it a true transition metal because its d subshell is complete in all its common oxidation states. This stable configuration explains why zinc compounds are generally colorless (unlike typical transition metals) and diamagnetic.

Zinc is a moderately reactive metal. At room temperature, it quickly forms a thin layer of zinc oxide (ZnO) that protects it from further oxidation. This protective layer makes zinc resistant to atmospheric corrosion, a property exploited in the galvanization of steel. Zinc reacts with dilute acids, releasing hydrogen gas and forming zinc salts: Zn + 2H⁺ → Zn²⁺ + H₂. It is amphoteric, also reacting with strong bases to form zincates: Zn + 2OH⁻ + 2H₂O → [Zn(OH)₄]²⁻ + H₂. At high temperatures, zinc burns in air with a bright bluish-white flame, forming zinc oxide. Zinc reacts with halogens, sulfur, and many other non-metals, especially when heated.

Zinc is synthesized in massive stars through various nucleosynthesis processes. It is mainly formed during the explosive burning of silicon in supernova explosions, as well as by slow neutron capture processes (s-process) in asymptotic giant branch stars (AGB). The five stable isotopes of zinc (\(\,^{64}\mathrm{Zn}\), \(\,^{66}\mathrm{Zn}\), \(\,^{67}\mathrm{Zn}\), \(\,^{68}\mathrm{Zn}\), \(\,^{70}\mathrm{Zn}\)) are produced by these mechanisms and dispersed into the interstellar medium during cataclysmic events.

The abundance of zinc in ancient metal-poor stars is particularly interesting to astronomers. The zinc/iron ratio ([Zn/Fe]) is used as an indicator of nucleosynthesis conditions in the early universe, as zinc and iron are produced by different processes. Very old stars often show a relative enrichment in zinc compared to iron, suggesting that the first supernovae had distinct characteristics from current stellar explosions. Absorption lines of ionized zinc (Zn II) in the spectra of distant quasars allow the study of the chemical composition of intergalactic gas clouds and the metal enrichment of the young universe.

N.B.:

Zinc is present in the Earth's crust at a concentration of about 0.0078% by mass, making it the 24th most abundant element. It is mainly found in ores such as sphalerite or zinc blende (ZnS), smithsonite (ZnCO₃), hemimorphite (Zn₄Si₂O₇(OH)₂·H₂O), and zincite (ZnO). Native zinc (pure metallic form) is extremely rare in nature. Zinc extraction is mainly done by roasting sulfide ore followed by reduction (pyrometallurgical process) or by leaching and electrolysis (hydrometallurgical process). Zinc is fully recyclable without loss of properties, and about 30% of world production comes from recycling, mainly from galvanized steel and brass alloys.