If all the empty space inside the atoms making up a human being could be removed, their volume would shrink to that of a grain of dust. Yet, our daily experience confronts us with the opposite reality: matter is solid, impenetrable. We do not pass through the ground, and our hand stops abruptly on the surface of a table. This apparent solidity is one of the most fundamental and counterintuitive phenomena in physics, resulting from the laws of quantum mechanics and electromagnetism.

The answer lies in three key principles: electron exclusion, the wave-like nature of particles, and electromagnetic repulsion forces. An atom is not a compact little ball, but a diffuse structure where particles are never exactly in one place. They rather form areas of probable presence, governed by energy levels and the physical fields that make them interact.

N.B. :

At the atomic scale, matter is more than 99.999% empty space. Atomic nuclei have a radius on the order of \(10^{-15}\) m, while atoms measure about \(10^{-10}\) m.

The first and deepest reason for the solidity of matter was formulated by physicist Wolfgang Pauli (1900-1958) in 1925. The Pauli exclusion principle states that two identical fermions (such as electrons) cannot be in the same quantum state.

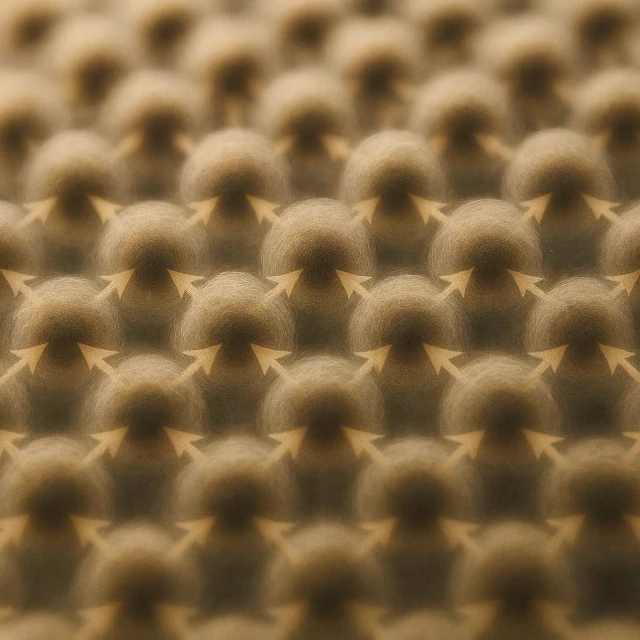

In an atom, electrons are organized in layers (orbitals) of defined energies. Each orbital can only accommodate a limited number of electrons with opposite spins. When two atoms approach each other, their electron clouds begin to overlap and the regions of electron presence probability form a quantum barrier without contact.

When two atoms approach, their valence electrons begin to occupy regions of space already associated with the quantum states of the other atom. The Pauli exclusion principle then forbids these identical electrons from sharing the same quantum state. To avoid this forbidden overlap, the system must increase its energy, which manifests as a very intense repulsive force at very short distances.

This repulsion is not, however, dominant at all times. At slightly greater distances, the electrostatic attraction between nuclei and electrons balances this repulsion, creating a stable equilibrium distance. It is this subtle balance between quantum attraction and repulsion that allows matter to remain coherent and solid, while preventing its gravitational collapse.

N.B. :

The "very short distance" corresponds to interatomic separations for which electron clouds begin to strongly overlap, typically less than 0.1 to 0.2 nanometers. The quantum kinetic energy imposed by the Pauli exclusion principle increases abruptly, generating an extremely steep repulsion. At "slightly greater distances", on the order of 0.2 to 0.3 nanometers, the electromagnetic attraction between nuclei and electrons dominates, creating a stable equilibrium distance that ensures the cohesion and solidity of matter.

Even in the absence of the exclusion principle, a major barrier remains. Electrons all carry a negative electric charge. Coulomb's law, established in the 18th century, states that charges of the same sign repel each other with a force inversely proportional to the square of the distance separating them \( F = k \frac{q_1 q_2}{r^2} \).

When two atoms approach, the negatively charged electron clouds interact first. The Coulomb repulsion between these clouds quickly becomes enormous as the distance decreases, preventing the penetration of the positive nuclei. Thus, even if atoms were mostly made of empty space, this "emptiness" is guarded by an extremely effective repulsive electric field. The hardness of a material, such as diamond, is directly related to the strength of chemical bonds and the intensity of this electronic repulsion.

N.B. :

A common analogy is to compare matter to two rapidly rotating fans. Although the space between the blades is empty, it is impossible to pass an object through rotating blades without collision. On a macroscopic scale, the probability of finding a free passage is practically zero. Similarly, even if atoms are essentially empty, electrons are never still. Their quantum clouds extend, fluctuate, and constantly renew. At our scale, this ceaseless activity results in a stable repulsive barrier, preventing material objects from passing through each other.

Quantum mechanics teaches us that particles like electrons also have a wave-like nature. The wavelength associated with an electron (De Broglie wavelength) depends on its momentum. When electrons are confined in a small volume (such as when trying to compress matter), their effective wavelength decreases, which increases their kinetic energy. This increase in energy due to confinement manifests as a pressure, called electron degeneracy pressure.

It is this same pressure that prevents white dwarfs, remnants of stars like the Sun, from collapsing under their own gravity. On our scale, it is an additional component that opposes the compression of matter, contributing to its rigidity. For two objects to pass through each other, one would have to either violate the exclusion principle or compress their electrons to the point of overcoming the degeneracy pressure, which would require densities and energies totally beyond reach under ordinary terrestrial conditions.

Under extreme conditions, exceptions appear and matter becomes "transparent":

| Principle / Force | Scale | Role in Impenetrability | Example / Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli exclusion principle | Quantum (fermions) | Prevents two electrons from occupying the same quantum state, generating a short-range repulsion. | Impossible to stack more than two electrons per atomic orbital. |

| Electrostatic repulsion (Coulomb) | Atomic / Molecular | Negatively charged electron clouds repel each other with intense force. | Repulsion between two magnets oriented with like poles facing each other. |

| Electron degeneracy pressure | Quantum / Stellar | Quantum pressure due to electron confinement, which resists compression. | Supports the equilibrium of a white dwarf against gravitational collapse. |

| Chemical bonds | Molecular / Macroscopic | Organize atoms into rigid structures (crystalline lattices, polymers) that transmit repulsive forces. | Rigid covalent lattice of diamond vs. weak stacking of graphite atoms. |

Reference sources: Nobel Prize - Wolfgang Pauli; Encyclopædia Britannica - Coulomb's Law; The Physics Hypertextbook - Standard Model.