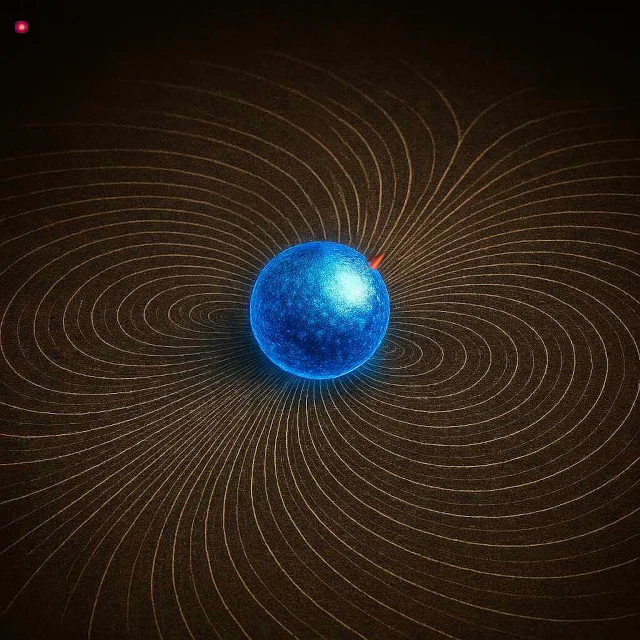

When we bring two magnets together, we feel an invisible force that attracts or repels them. This macroscopic manifestation of magnetism originates from the infinitely small, at the level of electrons. Each electron behaves like a tiny magnet, possessing what physicists call an magnetic moment. But how can an elementary particle, without internal structure, generate a magnetic field?

This apparent paradox challenged classical physics for decades. The answer lies in a purely quantum property: spin. Contrary to what its name might suggest, spin is not a physical rotation of the electron on itself. It is an intrinsic property, as fundamental as its electric charge or mass, with no classical equivalent (no image can be representative).

Electron charge (e): Electromagnetic property, constant and responsible for Coulomb interactions (electric forces and magnetic fields when the electron is in motion).

Spin (S): Quantum intrinsic angular momentum of the electron, independent of any orbital motion. It is not linked to a physical rotation of the particle.

In 1922, physicists Otto Stern (1888-1969) and Walther Gerlach (1889-1979) conducted a revolutionary experiment. They sent a beam of silver atoms through an intense magnetic field gradient, created by a device where one of the pole pieces has a sharp edge and the other a flat surface. According to classical physics, the magnetic moment of these atoms could have any orientation in space, like a vector that can adopt all possible orientations. When passing through this field with strongly varying intensity, the atoms should therefore be deflected differently depending on the orientation of their magnetic moment, creating a continuous trail on the detector screen from top to bottom.

However, the observation was stunning: instead of a continuous distribution, they saw only two distinct and separate spots, one at the top and one at the bottom of the screen, with nothing in between. This spatial quantization reveals that the magnetic moment of electrons can only take two discrete values, corresponding to two opposite orientations of the spin. We speak of spin "up" (↑) and spin "down" (↓), or more rigorously spin +½ and -½ (in units of the reduced Planck constant \(\hbar\)). This experiment constitutes the first direct evidence that magnetic properties are quantized at the atomic scale.

The magnetic moment of the electron, denoted \(\mu_e\), is directly proportional to its spin. Its experimental value is about \(9.284 \times 10^{-24}\) joules per tesla, a quantity called the Bohr magneton. This tiny value shows how weak the magnetic effect of a single electron is. Yet, when billions of billions of electrons align their spins in the same direction, as in an iron magnet, the cumulative effect becomes macroscopic. The magnetic moment of an electron results from two distinct contributions:

If we try to interpret spin as an actual rotation of the electron on itself, we encounter a major problem. To generate the observed magnetic moment, the surface of the electron would have to rotate at a speed much greater than that of light, which would violate the theory of relativity. Moreover, in the quantum framework, the electron is described by a wave function that cannot be considered a rotating classical sphere.

This paradox was resolved in 1928 by Paul Dirac (1902-1984). When Dirac wrote the equations of the electron while simultaneously respecting quantum mechanics and relativity, spin emerged naturally in the solutions, without needing to be artificially added, like a musical note that emerges when combining two harmonics.

| Particle | Spin | Magnetic moment (in magnetons) | Role in magnetism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron | ½ | 1.001 Bohr magneton | Mainly responsible for the magnetism of materials (permanent magnets, ferromagnetism). Its alignment in atoms creates macroscopic magnetic properties. |

| Proton | ½ | 2.793 nuclear magneton | Used in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to analyze molecules and in medical imaging (MRI) to visualize biological tissues. |

| Neutron | ½ | -1.913 nuclear magneton | Used in neutron scattering to study magnetic structures in materials. Its negative magnetic moment reveals its composite structure (quarks). |

| Photon | 1 | 0 | Mediates the electromagnetic force. Transports energy between charges and magnets, but has no intrinsic magnetic moment. |

In most materials, electrons pair up with antiparallel spins (oriented in opposite directions), resulting in almost total cancellation of their overall magnetic moment. These substances are called diamagnetic, such as water, copper, or gold, because their electrons are fully paired: each electron is associated with another of opposite spin, so the overall magnetic moment is zero in the absence of a field. When an external field is applied, there are no unpaired electrons to produce positive magnetization; the only possible response is then a very weak and opposite induced orbital polarization, which characterizes diamagnetism.

Conversely, when an atom has one or more unpaired electrons, and thus uncompensated spins, it develops a net magnetization under the action of an external magnetic field. This response characterizes paramagnetism, observable for example in aluminum or platinum.

In certain materials, the magnetic moments carried by these unpaired electrons can mutually influence each other and align collectively. The material then acquires stable magnetization even in the absence of an external field, a manifestation of ferromagnetism, as in iron, cobalt, or nickel.