The electrons of an atom are distributed in successive electron shells, each of which can contain a maximum number of electrons (2, 8, 18, 32, 50, 72 electrons depending on the shell). The valence shell is the outermost shell, farthest from the nucleus. The electrons in this shell are less strongly bound to the nucleus by electrostatic attraction than those in the inner shells. Consequently, only a small amount of energy is required to detach them from the atom or move them from one atom to another.

Copper has 29 protons and therefore 29 electrons, distributed as follows: 2 electrons in the first shell, 8 in the second, 18 in the third, totaling 28 electrons strongly bound to the nucleus. The 29th electron is alone in the fourth shell, much farther from the nucleus and therefore weakly bound. It is the electrons located in the outer shell (valence shell) that become free electrons, thus easily mobile.

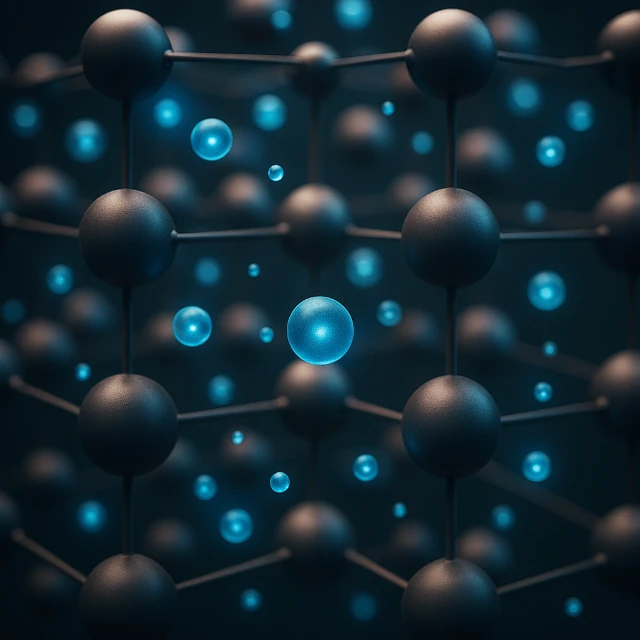

In a metal, the valence electrons are already free at room temperature. They move randomly and disorderly throughout the metallic structure (Brownian motion). Their thermal velocity is very high (~10⁶ m/s), but without a preferred direction, so the average net displacement velocity is zero. There is therefore no electric current because the movements cancel each other out statistically.

N.B.: The potential difference (voltage) does not free the electrons (they are already free), but imposes a preferential direction on them.

| Year | Scientist | Proposed model | Contributions and limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | Paul Drude | Classical free electron model Valence electrons move freely like a gas of classical particles in the metal | Contributions: Explains Ohm's law and electrical conductivity Limits: Incorrectly predicts the specific heat of metals and does not explain the variation of conductivity with temperature |

| 1927 | Arnold Sommerfeld | Quantum free electron model Applies the Fermi-Dirac quantum statistics to the free electron gas | Contributions: Corrects the specific heat problem, explains why only a few electrons participate in thermal properties Limits: Still ignores the periodic structure of the crystal lattice |

| 1928 | Felix Bloch | Band theory Electrons move in the periodic potential created by the atoms of the crystal lattice, representing the average effect of the electrostatic force exerted by the ions on the electrons | Contributions: Explains the difference between conductors, semiconductors, and insulators through allowed and forbidden energy bands Note: Current model used in solid-state physics |

Paul Karl Ludwig Drude (1863-1906) imagined free electrons as tiny solid balls moving through the metal like gas molecules. These "electron balls" bounce off the atoms of the metal lattice, somewhat like billiard balls on a table scattered with fixed obstacles.

Mental image: A cloud of small balls flying in all directions inside the metal, colliding with atoms and each other, exactly like the molecules of a gas enclosed in a bottle.

What this model explains: Ohm's law and basic electrical conductivity. When an electric field is applied, the balls drift gently in a preferred direction while continuing their disordered motion.

Problem: If electrons behaved like classical balls, metals should absorb much more heat than they actually do. The model also poorly predicts how electrical resistance varies with temperature.

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (1868-1951) abandoned the image of classical balls and applied quantum mechanics to the electron gas. Electrons are no longer simple balls: they obey the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that two electrons cannot occupy exactly the same quantum state.

Mental image: Imagine a giant human pyramid where each person represents an electron and occupies a unique position (Pauli principle). The lower levels are completely filled and fixed: it is impossible for these people to move without destabilizing the entire structure. Only the people at the upper levels, near the top (the Fermi energy), have the freedom of movement necessary to change position. At room temperature, about 99% of the electrons are "locked" in the lower levels, and only the top 1% can actually participate in thermal and electrical phenomena.

What this model explains: Why the specific heat of metals is so low even though they contain billions of free electrons. Only a tiny fraction of the electrons (about 1% at room temperature) can absorb thermal energy. The model also better explains thermal and electrical conductivity.

Problem: This model still treats the metal as an empty space where electrons move freely, completely ignoring the ordered and periodic presence of the atoms in the crystal lattice.

Felix Bloch (1905-1983) revolutionized the classical view by considering that electrons do not move in empty space, but in the periodic potential created by the atoms of the crystal lattice. Each electron therefore "swims" in an organized electrostatic field, which profoundly changes its displacement and energy properties.

Mental image: Imagine a wavy sea in which fish (electrons) swim. The regular waves represent the periodic potential of the atoms. The fish cannot move any which way: they must follow the wave structures of the sea, some areas being forbidden, others favorable to circulation. This image illustrates the formation of allowed and forbidden energy bands in the metal.

What this model explains: Electrical conduction and the electronic structure of solids, including the existence of conduction bands and forbidden bands. It accounts for many phenomena intertwined with quantum mechanics, such as the properties of semiconductors and the insulation of materials.

Problem: The model is complex to treat analytically and often requires approximations or numerical calculations. It remains theoretical and abstract for directly visualizing the individual behavior of electrons.

The free electron turns out to be a delocalized quantum entity, like a musical note that fills the entire concert hall, present everywhere simultaneously. Its behavior is entirely governed by the periodic order of the crystal lattice, where atoms stack identically in the three dimensions of space.