Every body persists in its state of rest or uniform rectilinear motion unless acted upon by an external force. This first law, also called the principle of inertia, establishes that velocity does not change without cause. In the universe, a planet continues its orbit not because a force pushes it, but because no force slows it down.

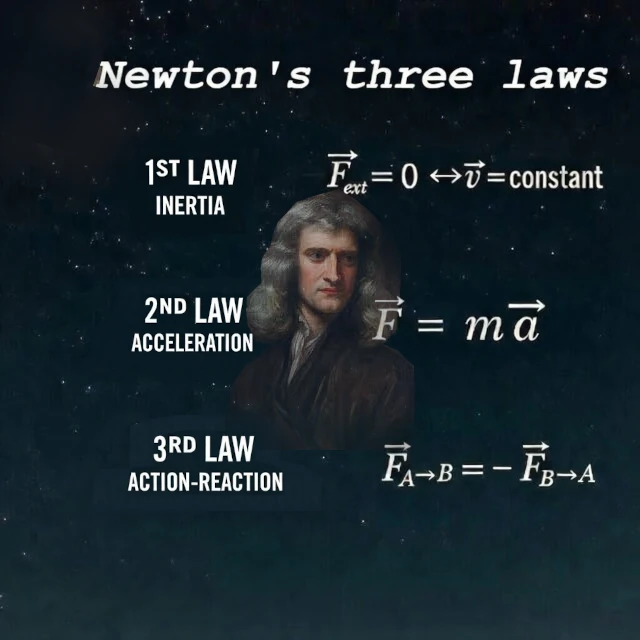

If the sum of external forces is zero, so is the acceleration: \( \boldsymbol{\sum \vec{F}_{\text{ext}} = 0 \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad \vec{v} = \text{constant}} \)

Concrete example: A cup placed on a table remains still as long as the forces acting on it are balanced. In interstellar space, a probe launched at 50,000 km/h continues indefinitely at the same speed, never slowing down, because no force opposes its motion.

The second law directly links the cause (force) to the effect (acceleration). In a Galilean reference frame, the sum of the forces applied to a material object is equal to the product of its mass and the acceleration it undergoes. The greater its mass, the harder it is to change its motion. This resistance to change is called inertia. The causal relationship is now explicit: a force always produces an acceleration in the direction in which it acts: \( \boldsymbol{\sum \vec{F} = m \cdot \vec{a}} \)

Concrete example: An empty shopping cart is easily set in motion with a gentle push, but when loaded with groceries, much more force is needed to move it. Tripling the mass requires tripling the force for the same effect.

Action is always equal to reaction. When body A exerts a force on body B, the latter simultaneously exerts on A a force of the same intensity, same direction, but opposite sense. These two forces act on different bodies, so they do not cancel each other out: \( \boldsymbol{\vec{F}_{A \to B} = - \vec{F}_{B \to A}} \)

Concrete example: A rocket ejects burning gases downward at high speed (action). In reaction, these gases exert an upward thrust of equal intensity on the rocket, propelling it into space. Even in the vacuum of space, where there is no air to push against, this principle remains fully effective because the forces act directly between the rocket and the ejected gases. This principle does not require any external support, contrary to popular belief. When the fuel is exhausted, the rocket maintains its speed in the vacuum of space (first law), continuing its trajectory without slowing down.

The three laws form a coherent system. The first defines the framework (inertial reference frame). The second quantifies the dynamic relationship. The third ensures the conservation of momentum in an isolated system. Together, they describe all movements, from the fall of an apple to planetary trajectories.

N.B.:

These laws, published in 1687 in the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, marked the birth of classical mechanics. Their formulation has remained unchanged since the 17th century, proof of their robustness.

| Law | Statement | Formula | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| First law (inertia) | A body remains at rest or in uniform rectilinear motion if no force acts on it. | \(\sum \vec{F} = 0 \Rightarrow \vec{v} = \text{cte}\) | A space probe in interstellar vacuum |

| Second law (dynamics) | The sum of the forces is equal to the product of mass and acceleration. | \(\sum \vec{F} = m \cdot \vec{a}\) | Pushing a broken-down car |

| Third law (action-reaction) | Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. | \(\vec{F}_{A \to B} = - \vec{F}_{B \to A}\) | Recoil of a gun when fired |

Source: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica and Encyclopædia Britannica - Newton's laws of motion.