Imagine for a moment that in the atom, the electron is no longer a small planet orbiting a sun-like nucleus, but a musical note, a vibration, a wave. This is the conceptual revolution triggered by Erwin Schrödinger (1887-1961) in 1926.

The Schrödinger equation does not tell us where the electron is with certainty, but where it is likely to be. It transforms the possible atomic space into a dance floor where the dancer's figures draw the probable orbitals.

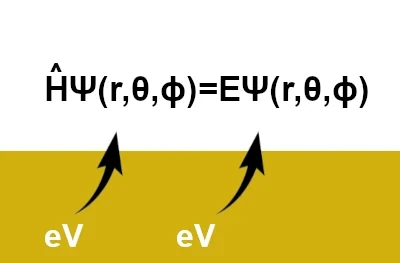

Schrödinger's equation is written as: \(\hat{H}\,\Psi(r,\theta,\phi)=E\,\Psi(r,\theta,\phi)\) where \((r, \theta, \phi)\) are spherical coordinates (r: radial coordinate, θ: polar coordinate, ϕ: azimuthal coordinate). However, in its simplest form, it is written as: \( \hat{H} \Psi = E \Psi \)

To unlock the mysteries of the atom, a special key is needed. This key is what physicists call the "wave function". It has a chic little name: Ψ (pronounced "Psi", like the beginning of "psyche" or Neptune's trident).

Imagine that Ψ is a kind of "navigation map" for the electron. This map does not say where the electron will go, but where it can go. More precisely, it describes the places where you are likely to find it, and the places where you will not find it.

On the left, \(\hat{H}\) represents "everything that happens in the atom" (the attraction of the nucleus, energy, constraints). On the right, \(E\) is the result: the energy that the electron must have to be stable in this configuration.

Solving this equation is like finding the right note on a piano so that it resonates perfectly in a room. You cannot play just anything: only certain notes (energies \(E\)) and certain ways of vibrating (functions Ψ) work harmoniously.

This was the great dilemma for physicists until Max Born (1882-1970) had a brilliant intuition. He said: "Do not look at Ψ itself, look at its reflection, its square, \(|\Psi|^2\)". It is like the smoke that reveals a probability cloud where the object was before the magician made it disappear. Thus, \(|\Psi|^2\) indicates, point by point in the space around the nucleus, the probability of the electron's presence.

In short, where \(|\Psi|^2\) is large is the "garden" of the atom, where the electron spends its time. Where \(|\Psi|^2\) is zero, it is a "desert", the electron never comes. The electron becomes less like a ball and more like a cloud, a trail of light, an elegant and fuzzy dance around the nucleus called an "orbital".

Applied to the hydrogen atom (one proton and one electron), Schrödinger's equation reveals a series of solutions, quantum states, each characterized by three numbers, often called quantum numbers. Each solution corresponds to an atomic orbital, a specific three-dimensional geometric shape that is the electron's privileged "dance zone".

Where Niels Bohr (1885-1962) saw electrons orbiting in neat circular orbits, like planets around the Sun, Schrödinger's equation reveals a much richer and more poetic universe. The solutions draw in space geometric shapes of elegant complexity.

These shapes are not mere mathematical fantasies. They are the keystone of chemistry. The geometry of the orbitals determines how atoms can bond with each other to form molecules. The direction of the p orbitals, for example, explains the angular shape of the water molecule (H2O). The richness of the d orbitals is responsible for the brilliant colors of the ions of transition metals. Thus, Schrödinger's equation, through its solutions, is the hidden grammar that dictates the structure of all the matter around us.

N.B.:

The mental image of the "electron cloud" is more accurate than that of the "particle in motion". An orbital is an instantaneous probability map. If you took an ultra-fast photograph of the atom, you would see the electron at one point; by superimposing millions of these photographs, you would see the shape of the orbital appear, like a trail of light left by a dancer on a dark stage.