Electron energy is the total energy an electron possesses in an atom, determined by its distance from the nucleus and its motion. This energy can only take specific quantized values called energy levels.

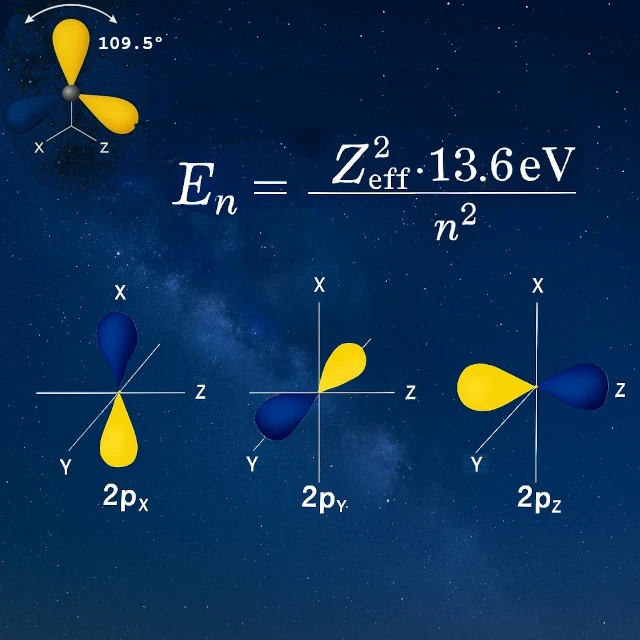

Take hydrogen, the reference atom in atomic physics. The electron gains energy by moving from the ground state (-13.6 eV for n=1) to excited states (-3.4 eV, -1.51 eV, -0.85 eV…) until complete ionization at 0 eV. These levels are all calculated using the formula En = -13.6/n², which also serves as a reference for comparing the binding energies of other elements.

This quantized nature of electron energy explains the diversity of chemical elements and their behaviors. Understanding it is essential in quantum chemistry, materials science, and many fields such as photosynthesis, cellular respiration, or photovoltaic cells.

In a multi-electron atom, the energy of an electron is not simply determined by its distance from the nucleus, but by a complex interaction between the attraction of the nucleus and the repulsion of other electrons. This effective energy, subtly modulated, dictates whether an atom will tend to lose, gain, or share electrons, thus giving rise to its characteristic chemical properties. In other words, electron energy defines the chemical identity of an element and how it interacts with other atoms. This explains why sodium reacts violently with water while neon remains completely inert.

To concretely illustrate how electron energy determines chemical behavior, let's examine carbon (Z = 6), a fundamental element of life.

Its electronic configuration 1s² 2s² 2p² shows that its 6 electrons occupy three distinct energy levels: the 2 electrons in the 1s shell are very strongly bound (low energy, -489.6 eV), those in the 2s shell have intermediate energy, and the 2 valence electrons in 2p are weakly bound (high energy, -30.6 eV), thus available to form chemical bonds.

• Far from the nucleus (outer shell) → High energy (close to 0 eV) → Easy to remove → Reactive

• Close to the nucleus (inner shell) → Low energy (very negative) → Hard to remove → Inert

A "high energy" electron (like the one in the 2p shell at -30.6 eV) is weakly bound to the nucleus: only 30.6 eV is needed to remove it completely. Conversely, a "low energy" electron (like the one in the 1s shell at -489.6 eV) is strongly bound: 489.6 eV is required to free it.

Imagine an object at height: the higher it is, the greater its potential energy and the easier it falls. An electron in a "high" orbital is like this object: it is "high" on the energy scale (less stable) and "falls" easily (reacts) to reach a more stable state.

In its isolated state, carbon has two unpaired electrons in its 2p orbitals (pₓ and pᵧ), which would suggest only two possible bonds. Yet, carbon forms four equivalent bonds. How? Through a process called sp³ hybridization: the 2s orbital merges with the three 2p orbitals to create four identical hybrid orbitals.

Before hybridization (isolated carbon):

After sp³ hybridization:

This precise tetrahedral geometry allows carbon to form four strong bonds in well-defined directions. Unlike a uniform distribution, valence electrons are localized in privileged directions at 109.5° from each other. This directional tetravalence makes carbon the molecular architect of life, capable of building chains, cycles, and three-dimensional structures of immense diversity, the foundation of all organic chemistry.

Electron energy transforms the abstract mathematics of orbitals into tangible chemical reality. The shapes and orientations of orbitals determine molecular geometry, their energies dictate reactivity, and hybridization explains the structural diversity of living matter.

From hydrogen to carbon, from methane to DNA, every molecule finds its architecture in the energetic distribution of its electrons. This fundamental understanding is not limited to theory: it guides the design of drugs, catalysts, semiconductors, and innovative materials. Electron energy is the bridge between quantum physics and the chemistry of the real world.