To effectively combat climate change, we must first understand its root causes. Greenhouse gas emissions, mainly carbon dioxide (CO2), are not random but the direct result of our economic and energy activities.

The Kaya Identity, named after Japanese economist Yoichi Kaya (1934-2020), provides a clear mathematical framework for breaking down this complex phenomenon into key factors. This identity is not a predictive model, but an accounting tool for analyzing possible levers of action against climate change.

Developed in the late 20th century, this identity has become a fundamental tool for the IPCC and policymakers. It allows for the modeling of future emission scenarios and the identification of possible levers for action.

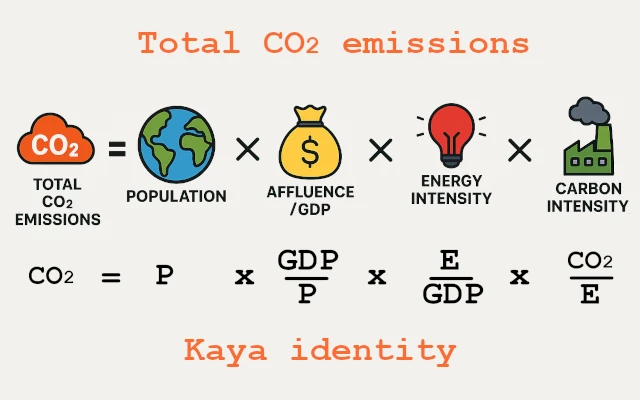

The Kaya Identity establishes a multiplicative relationship between global CO2 emissions and four socio-economic and technological factors: \( \text{CO2} = \text{Population} \times \frac{\text{GDP}}{\text{Population}} \times \frac{\text{Energy}}{\text{GDP}} \times \frac{\text{CO2}}{\text{Energy}} \)

For clarity, it is often rewritten by defining intermediate ratios: \( \text{CO2 Emissions} = \text{P} \times \text{g} \times \text{e} \times \text{f} \)

N.B.:

The Kaya Identity is an identity, not an equation in the strict sense. This means it is always true by mathematical construction; it serves to organize thought and quantify the relative contributions of each factor, not to predict the future in a deterministic way.

The strength of the Kaya Identity is to highlight the four main levers that can be used to reduce CO2 emissions:

1. Population (P): A delicate and long-term lever, linked to demographic, education, and health policies. Population growth mechanically amplifies the other factors.

2. Prosperity per capita (g): Reducing this factor means giving up economic growth, a politically and socially complex option. The challenge is rather to decouple growth from emissions.

3. Energy intensity (e): This is the lever of energy efficiency. Reducing 'e' means producing the same wealth with less energy, through technological innovation (buildings, transport, industry) and behavioral changes.

4. Carbon intensity of energy (f): This is the most powerful and direct lever. Reducing 'f' involves decarbonizing the energy mix by replacing fossil fuels (coal, oil, gas) with low-carbon energies (renewables, nuclear).

| Factor (Symbol) | Meaning | Objective to Reduce CO2 | Main Means of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Total number of inhabitants | Long-term stabilization | Education, health, family planning |

| GDP/capita (g) | Standard of living / Economic wealth | Decouple growth and emissions | Circular economy, sobriety |

| Energy intensity (e) | Energy consumed per unit of GDP | Decrease (efficiency) | Building insulation, efficient engines, digital |

| Carbon intensity (f) | CO2 emitted per unit of energy | Strong decrease (decarbonization) | Renewable energies, nuclear, CO2 capture |

While the Kaya Identity is a valuable pedagogical and analytical tool, it has certain limitations.

It focuses only on energy-related CO2, excluding other greenhouse gases (water vapor, methane, nitrous oxide) or emissions related to land use (deforestation). The simplicity of this identity does not account for the complex interactions and feedback loops (positive or negative) between the factors. For example, energy efficiency gains (decrease in 'e') can sometimes lead to an increase in consumption (rebound effect), partially offsetting the benefit. Similarly, a temperature increase due to CO2 emissions can increase the concentration of water vapor in the atmosphere (a potent greenhouse gas), creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies the initial warming, a phenomenon not captured by the equation. It says nothing about the technical, economic, or political feasibility of reducing each factor.

The factorization implicitly assumes that population, wealth, energy intensity, and carbon intensity are independent. In reality, these variables are strongly coupled.

Despite its limitations, the Kaya Identity structures the construction of emission scenarios used by the IPCC to project climate evolution. The different scenarios (SSP1-1.9, SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5…) correspond to contrasting trajectories for each of the four factors. For example, the very ambitious SSP1-1.9 scenario assumes a population (P) that peaks and then slightly declines, moderate economic growth (g) focused on sustainability, very rapid improvement in energy efficiency (e), and extremely rapid decarbonization of the energy system (f). Conversely, a high-emission scenario like SSP5-8.5 projects strong growth in P and g, combined with limited progress on e and f, leading to a very high P×g×e×f product.

A strong mitigation scenario (limiting warming to 1.5°C) necessarily implies a very rapid and deep reduction in carbon intensity (f) and energy intensity (e), partly offsetting the expected growth in population (P) and per capita wealth (g). For example, to halve global emissions by 2050 compared to 2020, while assuming moderate growth in P (about +20%) and g (about +80%), calculations show that energy intensity (e) would need to be reduced by about 40% and, above all, carbon intensity (f) would need to be divided by more than 4. This concretely illustrates the equation: CO2 = P×g×e×f must be halved, despite the increase in P and g, thanks to drastic reductions in e and f.

Although these figures may seem daunting, they define a precise framework for action. The reduction in energy intensity is already underway in many countries thanks to technological progress, and the potential for decarbonizing the energy mix (reduction in 'f') is immense with renewable energies and nuclear power. The challenge is less technological than political and economic: it is about carrying out this transition at an unprecedented speed and scale.

| Kaya Factor | Current Trend (approx.) | 2050 Target (1.5°C) | Additional Effort Required | Examples of Concrete Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | +0.8% / year | +0.5% / year (stabilization) | Accelerate demographic transition through education and access to rights | Girls' education, reproductive health, family planning |

| GDP/capita (g) | +1.5% to +2% / year | Decouple growth and emissions | Halve the carbon intensity of growth | Circular economy, services, material sobriety |

| Energy intensity (e) | -1.5% / year | -3% to -4% / year | Double the pace of efficiency gains | Massive building renovation, electric vehicles, industry 4.0 |

| Carbon intensity (f) | -1% / year | -7% to -10% / year | Multiply the decarbonization rate by 7 to 10 | Triple renewables by 2030, phase out coal, green hydrogen, nuclear |

Sources: IPCC AR6 (2022), IEA Net Zero by 2050 (2021), UN - Population Prospects.

Thus, the realistic climate strategy focuses mainly on an accelerated transformation of the 'e' and 'f' factors, while supporting a natural evolution of 'P' and steering 'g' growth towards more sober models. The Kaya Identity shows that success depends on an exponential improvement in our energy efficiency and the cleanliness of our energy.