The human mind is fascinated by extremes and limits. We conceptualize absolute cold (thermodynamic zero at 0 Kelvin) and perfect nothingness (the total absence of matter, energy, space, and time) as if they existed.

These concepts seem logical, even necessary, to delimit our reality. Yet, when fundamental physics takes hold, it reveals a troubling truth: these two states do not seem to exist in our universe. They are not reachable destinations, but rather horizons that recede as we approach them. This impossibility is not an accident; it arises from the most intimate laws of nature.

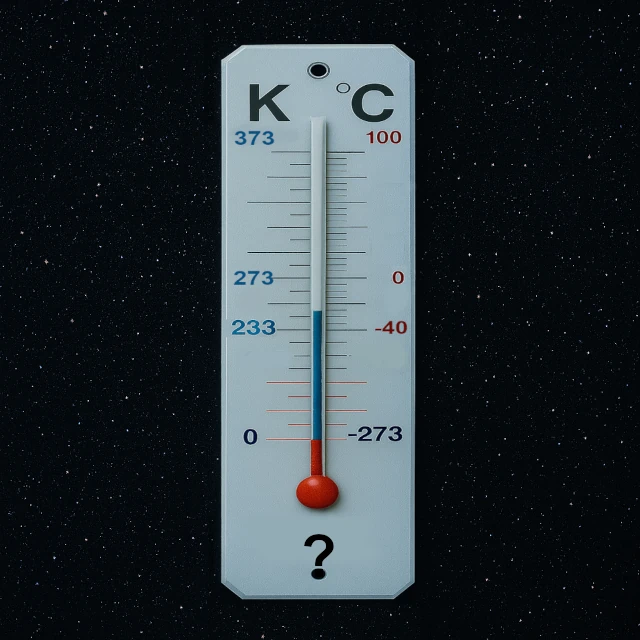

The quest for ultimate cold has a long history. In the 18th century, scientists like Guillaume Amontons (1663-1705) already spoke of "extreme cold." The concept of absolute zero was firmly established in the 19th century. It represents the state where the thermal energy of a system is minimal, where atoms would cease all movement.

However, quantum mechanics, born in the early 20th century, imposed a fundamental prohibition. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle (1927) forbids a particle from having a perfectly defined position and momentum (both zero). Even at its lowest energy level, a system possesses zero-point energy.

Thus, reaching 0 K would mean completely freezing the quantum nature of matter, which is impossible. Physicists can get extraordinarily close (to a few billionths of a Kelvin), but the "wall" of the uncertainty principle remains insurmountable. Absolute zero is an asymptotic limit.

N.B.: What is temperature?

From a microscopic point of view, temperature is not a substance, but a measure of the average thermal agitation of the particles that make up matter (atoms, molecules). The greater this agitation, the higher the temperature. Absolute zero would theoretically correspond to the complete cessation of this agitation. Quantum mechanics forbids this state of perfect stillness, ensuring a minimum residual energy even at the lowest level.

Similarly, the notion of nothingness seems just as elusive. Our intuition of "void" is a totally empty space. Yet, quantum field theory teaches us that what we call void is actually a dynamic and complex entity: the quantum vacuum.

In this vacuum, virtual particle-antiparticle pairs appear and disappear constantly, borrowing their energy from the uncertainty principle in the form \(\Delta E \Delta t \ge \frac{\hbar}{2}\). This is not a theoretical artifact; effects like the Casimir force (predicted in 1948, measured precisely later) prove it experimentally.

Let's go further. Spacetime itself, the framework of all existence, is a "something" with properties (curvature, expansion). If, as some cosmological models suggest, the "Big Bang" marks the emergence of spacetime, then the question "what was there before?" might be nonsensical, because there may not have been a "before" without time to measure it. In this context, "nothingness" would not even be a void in spacetime, but the total absence of spacetime itself, a notion so radical that it defies our ability to conceptualize it.

Conceptualizing nothingness is to give it an existence it does not have. As physicist Lawrence Krauss (b. 1954) pointed out in his book "A Universe from Nothing," the "nothing" of physics is not the philosophical "nothing."

The analogy between the unattainability of absolute zero and the nonexistence of nothingness is not just poetic coincidence. It points to an underlying principle: nature seems to reject states of total absence, of perfect nullity.

This impossibility is a guarantor of the existence and stability of the universe. Without zero-point energy, atoms could collapse. Without vacuum fluctuations, there might not have been seeds for the inhomogeneities that led to galaxies. The fact that the universe is filled with a fundamental energy (vacuum energy, or cosmological constant) is another clue in this direction.

The two limits of absolute zero and nothingness are therefore not boundaries of the universe, but limits of our classical concepts. They refer us to the founding oddities of quantum and relativistic reality.

| Concept | Intuitive Definition | Physical Reality | Cause of Impossibility | Consequence for the Universe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Zero (0 K) | Temperature at which all thermal agitation ceases. | Unattainable limit. Zero-point energy persists. | Heisenberg uncertainty principle (\(\Delta x \Delta p \ge \frac{\hbar}{2}\)). | Stability of atoms, existence of matter. |

| Nothingness / Perfect Void | Total absence of matter, energy, space, time. | Does not exist. The "void" is a dynamic quantum vacuum. | Quantum fluctuations of the vacuum (\(\Delta E \Delta t \ge \frac{\hbar}{2}\)). | Possibility of particle creation, seed of cosmic structures, vacuum energy. |

Sources: Principles of quantum mechanics (Heisenberg, Dirac). Modern cosmology (vacuum energy, inflation). Casimir effect.

Science tells us how something came from almost nothing. But the mystery of why there is "something" rather than absolute nothingness remains at the frontiers of physics and philosophy.

This double impossibility leads us to a dizzying question: are these two unattainable limits—absolute zero and nothingness—precisely what makes our existence possible? If absolute zero were attainable, matter would collapse, deprived of the zero-point energy that maintains atomic structure. If perfect nothingness existed, there would be no quantum fluctuations to initiate the genesis of particles, nor a spatiotemporal framework for any story to unfold. The fundamental laws of physics seem to favor, or at the very least allow, the emergence of complexity.

Our presence in the universe would then not be a contingent accident, but a consequence inscribed in the very impossibility of nothingness and absolute cold.