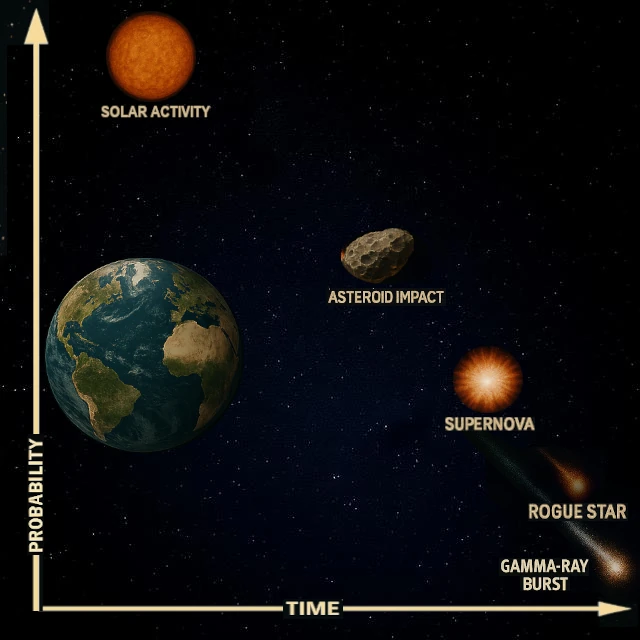

Since the dawn of humanity, the sky has been a source of wonder and apocalyptic fears. Prophecies of the end of the world often originate from misunderstood astronomical phenomena. Today, science allows us to separate fact from fiction, quantify the real risks posed by the universe, and reassure us that our planet is a far more resilient and fortunate ark than it seems.

Solar flares and coronal mass ejections represent the closest and most probable threat. These events eject billions of tons of solar plasma into space at staggering speeds. Their power is such that a single major CME releases energy equivalent to millions of simultaneous nuclear bombs.

The main risk for our modern, technology-dependent civilization is "extreme space weather." When this wave of charged particles and electromagnetic radiation hits Earth, it violently interacts with our magnetosphere. It can induce powerful electric currents (geomagnetically induced currents) in power grids, pipelines, and communication cables.

Several factors protect us and mitigate the risks. First, our planet has an exceptional natural shield: its magnetic field, which deflects most solar particles toward the poles, creating the northern and southern lights. Second, we are not ignorant. Agencies like NASA and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) continuously monitor the Sun with fleets of satellites (SOHO, SDO, ACE, Parker Solar Probe). These observations allow for solar activity forecasts with 24 to 48 hours' notice, giving power grid operators enough time to take preventive measures (isolating parts of the grid, activating compensation systems).

Additionally, the design of critical infrastructure has evolved since the last major event, the Carrington Event of 1859. Construction standards and power grid protections now incorporate this threat. Finally, outages caused by a superstorm would likely be regional and temporary (lasting from a few days to a few weeks), requiring costly repairs but not equating to a global, lasting civilizational collapse.

The scenario is cinematic: a space rock several kilometers in diameter strikes Earth, causing an impact winter and mass extinction. This is likely what sealed the fate of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

Collisions with bodies over 10 km in diameter, capable of causing mass extinctions, are rare events. Solar System dynamics models show that most potentially hazardous objects are either already identified or gravitationally stabilized by Jupiter.

The international astronomical community, through programs like Pan-STARRS and the future Vera C. Rubin Observatory, diligently catalogs and tracks NEOs (Near-Earth Objects). To date, over 95% of asteroids larger than one kilometer—planet killers—have been identified, and none show a collision trajectory with Earth for the coming centuries.

The explosion of a dying star within a hundred light-years could flood Earth with X-rays and cosmic rays, with consequences similar to a GRB scenario.

There are currently no candidate stars for a supernova within this "danger zone" around the Sun. Massive stars capable of exploding as supernovae are rare, bright, and well-known. Betelgeuse, often mentioned, is about 640 light-years away—a safe distance. The closest star posing a distant risk, IK Pegasi B, is a white dwarf that could become a Type Ia supernova… but in several million years and at 150 light-years away. Space is vast, and dangerous stars are very far away.

Our solar system is not an isolated sanctuary. It traverses the galaxy and could, theoretically, cross paths with another star. A too-close passage would gravitationally disrupt the Oort Cloud, sending a shower of comets toward the inner planets, and could even destabilize planetary orbits.

The stellar density in our corner of the galaxy is very low. Stars are separated by light-years of empty space. Simulations, such as those conducted by Coryn Bailer-Jones (active in the 21st century), show that the probability of a star passing within 0.5 light-years of the Sun (close enough to disrupt the Oort Cloud) is about once every 50 million years. Even then, the major risk would be a moderate increase in the comet rate over thousands of years, not an instantaneous cataclysmic bombardment.

A GRB is the most energetic explosion in the universe, releasing in seconds the equivalent of the energy the Sun will emit over its entire lifetime. A jet directed at Earth could sterilize half the planet by destroying the ozone layer, exposing life to deadly ultraviolet radiation.

These events are extremely rare in a galaxy like ours. They are associated with the collapse of very massive, fast-rotating stars, or the merger of neutron stars—phenomena that do not occur in our immediate stellar neighborhood. To be a direct threat, a GRB would have to occur within a few thousand light-years and its narrow jet would have to be perfectly aligned with Earth. The combined probability of these conditions is infinitesimal. Moreover, our galaxy, the Milky Way, is not the type of galaxy (low in star formation and metallicity) that favors the production of these cosmic monsters.

| Cosmic Threat | Critical Distance / Danger Zone | Estimated Frequency (in the Galaxy or Near Earth) | Main Protection / Mitigation Factor(s) | Maximum Plausible Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme Solar Activity (Super-flare / Giant CME) | Earth (direct impact) | Major event: every ~100 to 500 years (e.g., Carrington 1859, 1989, 2003). | Earth's magnetosphere, forecasting capability (satellites), hardening of power grids. | Prolonged regional power outages, disruption of satellites and communications, costly repairs. |

| Asteroid or Comet Impact (> 1 km) | Intersection trajectory with Earth's orbit (< 1 AU). | Global impact: ~once every 50 to 100 million years (e.g., Cretaceous-Paleogene). | Protective role of Jupiter, surveillance programs (NEO), deflection tests (DART). Over 95% of the largest objects cataloged. | Impact winter, global ecological collapse, mass extinction. |

| Nearby Supernova (Type II or Ia) | < 25-50 light-years for severe biological effects. | Near the Solar System: < once per billion years. No known candidates in this zone. | Vast distance to massive stars. Atmospheric shield (attenuates secondary cosmic rays). | Degradation of the ozone layer, increased UV and cosmic rays at ground level over centuries. |

| Passage of a Disruptive Rogue Star | Passage within < 0.5 light-years to disrupt the Oort Cloud. | ~1 star every 50 million years in this zone. Very close passage (< 10,000 AU): >1 billion years. | Low local stellar density. Long response time of the Oort Cloud (comets over millennia). | Significant and prolonged increase in the rate of comets entering the inner solar system. |

| Gamma-Ray Burst (GRB) Nearby and Aligned | < 1,000 - 10,000 light-years with perfectly aligned jet. | In the Milky Way: ~1 every 5 to 10 million years. With alignment toward Earth: extremely rare. | Rarity of progenitor stars (Wolf-Rayet, neutron star mergers). Directional randomness (narrow jet). | Sterilization of a hemisphere by ozone layer destruction, intense UV irradiation. |

This "threat" is more an inevitable chapter in the history of the solar system than an imminent risk to our civilization. It is an astrophysical certainty: in about 5 billion years, the Sun, running out of hydrogen, will begin to swell immensely to become a red giant, likely engulfing Mercury, Venus, and possibly even Earth.

The unknown is real, but the universe is not capricious. It is vast, slow, and remarkably tolerant of Earth's existence.