What if life was neither the result of contingency nor of finality, but the expression of a phase transition of matter subjected to an energy flux?

How, from inert molecules, could life have emerged on Earth about 3.8 billion years ago? This question can be approached from a modern angle by examining the principle of the minimal cell. The goal is to determine the most elementary organizational form capable of maintaining a regulated internal state in the face of environmental variations and reproducing autonomously.

Source: Classic theories by scientists such as Alexander Oparin (1894–1980) and J.B.S. Haldane (1892–1964) proposed that life could gradually emerge from a "primordial soup" of chemical elements. Today, the concept of the minimal cell allows us to consider the origin of life as the spontaneous formation of a system capable of maintaining internal balance and reproducing itself, based on fundamental physical and chemical laws.

Modern cells are the fundamental unit of all living organisms (bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes). However, even the simplest cells are already molecular cathedrals of dizzying complexity.

In humans, the body is estimated to contain about 37 trillion cells, distributed among more than 200 different cell types. Each cell type has specific morphological and biochemical characteristics adapted to its biological functions.

Source: According to Geoffrey H. Stoeckius and collaborators (2021), more than 200 distinct cell types have been identified in humans, each specialized for precise physiological functions. Endosymbiotic theory (Lynn Margulis, 1967): Explains the origin of mitochondria and chloroplasts through the incorporation of bacteria into eukaryotic cells.

The primitive Earth offered a gigantic natural experiment: trillions of chemical reactions were carried out simultaneously over hundreds of millions of years. Every warm pond, every hydrothermal vent, every porous mineral or clay grain formed a miniature laboratory where organic molecules could assemble. Constantly stirred by natural cycles over long periods, these molecules gradually followed the chemical pathways leading to the building blocks of life: amino acids, sugars, lipids, and RNA bases.

N.B.:

While debates about the origin of life remain lively, one point is consensus: amino acids, which form proteins, are essential molecular building blocks for any living organism. Moreover, their natural formation is possible in space, as they have been found in meteorites. This suggests that amino acids were probably available on the primitive Earth.

Source: The conditions of the early Earth, with its hydrothermal vents, warm ponds, and catalytic minerals, were proposed as "natural laboratories" for prebiotic synthesis by Stanley Miller (1930–2007) and Harold Urey (1953).

Atoms are in constant motion due to thermal agitation, which causes slight displacements and vibrations within molecules. Weak chemical bonds, such as hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions (attractive or repulsive forces), hold atoms together in primitive carbon-based molecules. Carbon, with its 4 stable covalent bonds, is the perfect element for building molecular assemblies.

The random vibrations of molecules, behaving like tiny electric magnets, allow chemical structures to simultaneously explore different spatial conformations. New molecular forms are continuously created, increasing the chances of stable arrangements. This diversity constitutes a virtually unlimited reservoir of molecular forms, of which only electromagnetically stable structures will persist long enough to be subjected to natural selection.

Source: As shown by the work of Max Delbrück (1949) on stochastic fluctuations in biological systems, these random movements allow chemical structures to simultaneously test many conformations. Molecular self-assembly: Work by Jean-Marie Lehn (born 1939) on supramolecular chemistry, focusing on weak interactions (hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces).

Certain molecular configurations will allow natural self-replication, which relies on a simple principle: structural complementarity.

A macromolecule (a single strand folded into a 3D shape) acts as a mold whose shape and electrical charges precisely attract certain free chemical elements present around it. These free elements align along the strand according to their chemical compatibility to form a second distinct complementary chain (like a photographic negative). The result is a two-chain paired structure, assembled piece by piece from the surrounding components.

The two chains held together by hydrogen bonds eventually break naturally, due to the thermal agitation of the environment. This energy balance is crucial because enough agitation is needed to allow encounters and separations, but not too much to preserve the integrity of the assembled structures (warm ponds, hydrothermal vents, etc.). This complementary macromolecule can itself serve as a mold to recreate the initial sequence.

Through this purely physico-chemical mechanism (attraction → alignment → pairing → separation → restoration of the initial sequence), it becomes possible to understand how RNA macromolecules capable of self-replication could have emerged spontaneously on the primitive Earth.

Source: The spontaneous replication of RNA molecules fits within the framework of the RNA world theory, proposed by Walter Gilbert (1986), which suggests that RNA could both store information and catalyze chemical reactions.

The system becomes auto-catalytic: certain RNA molecules replicate faster than others, by recruiting free nucleotides (A, G, C, U) more efficiently. Small errors and variations create new forms, with different copying speeds and stabilities. The fastest and most stable molecules proliferate, while the least efficient disappear. This selection is natural and results directly from the laws of chemical kinetics in a non-equilibrium system, i.e., agitated and fed by a constant flow of matter.

Source: The dynamics of autocatalytic selection echo the models proposed by Eigen and Schuster (1977) on hypercycles, describing how competition and replication favor certain molecules in non-equilibrium chemical systems.

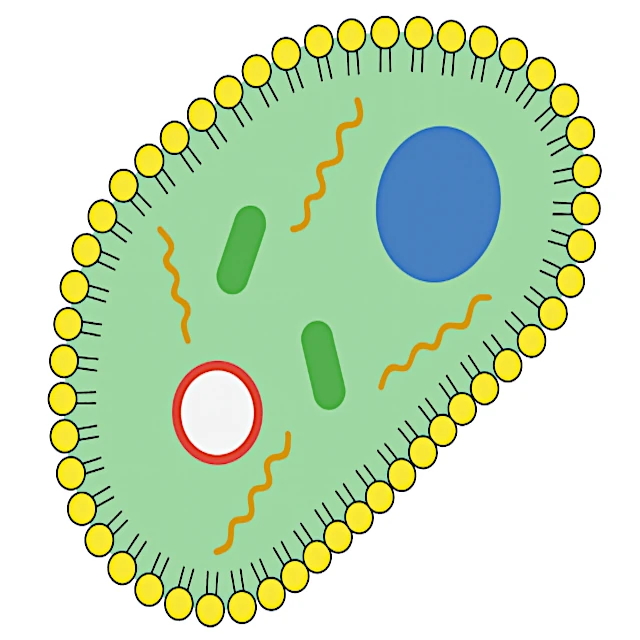

The transition from replicative molecules to a true cell requires the appearance of a membrane compartment. Biological membranes are made of phospholipids, amphiphilic molecules that spontaneously organize into bilayers when in an aqueous environment. This self-assembly is natural: it is thermodynamically favorable and occurs without the need for external intervention, much like a soap bubble that forms spontaneously on the surface of water.

A protocell protected by a lipid membrane and containing RNA molecules capable of self-replication has the essential characteristics of a minimal living organism. It has a metabolism (production of its own internal components), a reproductive capacity (cell division), and a transmissible information carrier (RNA). From this stage, Darwinian evolution can fully operate, favoring the most efficient protocells to grow and divide in their environment.

Source: The self-assembly of phospholipids into bilayers has been experimentally observed and is explained by the thermodynamics of amphiphilic systems (Bangham et al., 1965). This shows that membrane formation does not require biological intervention.