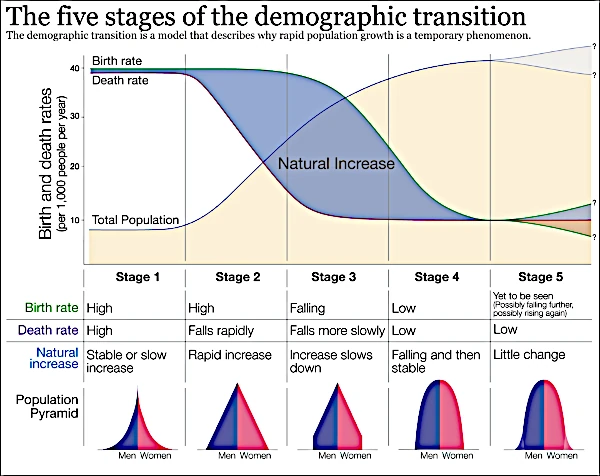

The demographic transition refers to the gradual shift of a population from a traditional demographic regime—characterized by high birth and death rates—to a modern regime, where both rates are low. This phenomenon is closely linked to industrialization, and to sanitary, medical, and technological progress. It generally breaks down into four phases:

All human societies seem to go through this transition sooner or later, but the timing varies greatly from continent to continent. Western Europe began this transformation as early as the 18th century, while some sub-Saharan African countries are still in phase 2 or 3 today. This time lag generates significant geopolitical dynamics: migratory pressure, unbalanced urban growth, and resource tensions.

The demographic transition acts as an irreversible phase change in a complex system: once the mechanisms are triggered (control of mortality, control of births, changes in social behavior), a return to the previous regime becomes highly improbable, like a thermodynamic state change. This structural shift profoundly transforms the balance between births and deaths, thus modifying the pace of evolution of human societies.

One of the major consequences is the aging of the population. In physics, we would say that the "population" system increases its temporal entropy: the proportion of older states grows with time. In a high birth rate society, the age pyramid is wide at the base. But as soon as fertility falls, this base narrows, and the proportion of older individuals grows mechanically. In France, for example, the proportion of over-65s has risen from 10% in 1970 to over 21% in 2025. This shift directly affects the dependency ratio: the number of inactive people per active person.

Another effect: the decline in the fertility rate. This parameter is a macroscopic marker of the reproductive dynamics of a living system. The generational renewal threshold - often set at \( 2.1 \) children per woman - is no longer reached in most developed countries. This phenomenon results from the generalization of access to education, particularly for women, the spread of contraceptive methods, the delay in the age at first childbirth, and contemporary economic trade-offs (cost of children, job instability, urbanization).

This demographic slowdown is also reflected in a decline in the natural growth rate. On a global scale, the annual demographic growth rate has fallen from over \( 2\% \) in the 1960s to around \( 0.8\% \) in 2025, according to United Nations projections. Some regions are already experiencing natural demographic decline, particularly Eastern Europe and Japan, a phenomenon still offset elsewhere by the growth of young populations in sub-Saharan Africa.

The implications of this dynamic are systemic:

This process is also accompanied by an urban planning transition. Megacities are absorbing the majority of the residual demographic growth, leading to local overcrowding, increased energy flows, and water stress. This puts a strain on infrastructure systems (housing, transport, sanitation), causing runaway effects analogous to the positive feedback observed in nonlinear systems physics.

Finally, the demographic transition marks a profound cultural change. The child is no longer an economic necessity or a social obligation, but a personal, considered choice, often deferred. This shift in the relationship to human reproduction is unique in the biological and sociological scale of the species Homo sapiens. By modifying the fundamental parameters of reproduction and survival, the demographic transition redefines the life cycle, social organization, and economic structures.

After the classic four-phase demographic transition, some demographers and social science researchers are now talking about the emergence of a fifth phase characterized by sustained demographic decline in several advanced societies. This phase is distinguished not only by very low fertility, but also by a new socio-economic and biological dynamic, associated with several interdependent factors.

The systemic consequences are significant and can be compared to a dissipative system out of equilibrium that tends towards a new stationary state, characterized by a stable or declining population:

This phenomenon also raises fundamental questions about the sustainability of the global demographic growth model, the ability of societies to adapt to declining populations, and the role of public policy in stimulating or regulating demographic dynamics. Thus, the fifth phase could represent a new stage in human socio-biological evolution, marked by a complex interaction between biological, environmental, economic, and cultural factors.

The interaction between global climate change and the demographic decline underway in several regions of the world can generate unexpected systemic risks, otherwise known as a terminal shock affecting global socio-economic and ecological stability. These risks result from complex nonlinear feedback, characterized by runaway phenomena coupled with structural limits in human adaptive capacities.

From a physical point of view, this shock can be conceptualized as the convergence of two dynamic processes with different but strongly interdependent time scales:

Among the specific risks identified, beyond the well-documented threats, are phenomena not anticipated by human intuition but likely to appear through complex probabilistic mechanisms and systemic feedback:

These so-called "unexpected" or "non-intuitive" risks often arise from the interaction of multiple coupled factors, generating high-dimensional dynamics where strange attractors or bifurcations may appear. Their probability of occurrence is low individually, but their potential impact is high enough to justify systemic integration into demographic and climate forecasting models.

The demographic transition marks a turning point in the history of humanity. It is not just a matter of numbers: it expresses the ability of the human species to emancipate itself from natural and environmental constraints, but also to collectively manage the effects of this emancipation. In this sense, it is fully part of the cultural evolution of humanity, alongside language, agriculture, and writing.