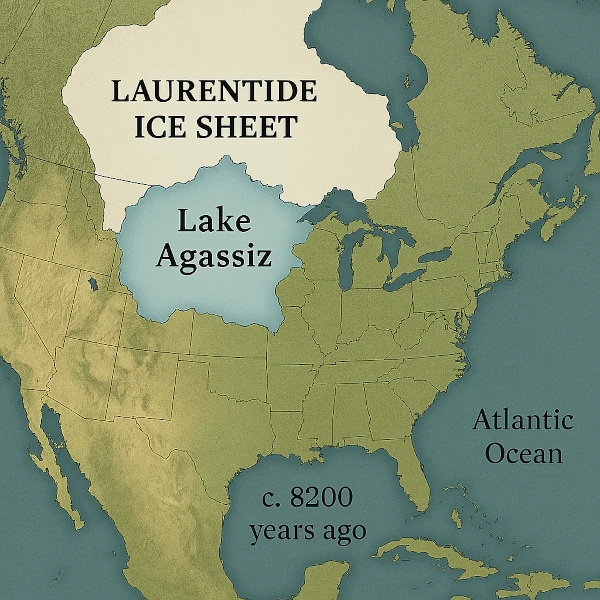

About 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age, a vast freshwater lake formed in the heart of the North American continent: Lake Agassiz. Its origin is directly linked to the gradual melting of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. At its peak, this lake covered up to 440,000 km², an area larger than the current Black Sea.

The draining of Lake Agassiz, 8,200 years ago, would have released up to 150,000 km³ of fresh water into the North Atlantic. To illustrate this volume, it is equivalent to about 60 million Olympic swimming pools or nearly half the volume of the Mediterranean Sea. This mass of water altered the salinity and density of the ocean, affecting thermohaline circulation.

The Jökulhlaup Phenomenon refers to a sudden release of water due to the rupture of a glacial dam. In the case of Lake Agassiz, it is one of the largest in recent geological history. The water would have flowed via the St. Lawrence Valley or Hudson Bay, disrupting the global ocean balance.

This massive and sudden outpouring of fresh water led to a slowdown in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This phenomenon caused the 8.2 ka event, which cooled the Earth.

Today, the regions where Lake Agassiz once existed are primarily composed of Canadian prairies and the American Midwest states. Geological traces of the drainage are visible in canyons, depressions, and fossil shorelines, which bear witness to this ancient expanse of water.

Greenland ice cores testify to this abrupt temperature drop through the analysis of oxygen isotopes (δ18O). Marine sediments confirm the massive influx of fresh water through isotopic changes and the presence of glacial detrital particles.

The symbol δ18O denotes the isotopic ratio of oxygen 18 to oxygen 16 in a sample (ice, water, sediment, etc.), compared to a standard reference. It is expressed in parts per thousand and allows the analysis of past climate variations. In ice cores, a lower δ18O indicates cooling: during glacial periods, oxygen 16-enriched water vapor precipitates as snow, leaving the oceans enriched in oxygen 18.

The sudden draining of Lake Agassiz illustrates a phenomenon of Physical Bifurcation, in the sense of nonlinear dynamic systems. In this context, a bifurcation corresponds to an abrupt regime change in the hydrological system, induced by reaching a critical threshold. By accumulating increasing volumes of glacial meltwater, the lake exerted increasing pressure on natural barriers, including moraine dikes or residual ice caps.

For thousands of years, nothing happened; the ice formed a natural dam retaining the meltwater accumulated in Lake Agassiz. But under the combined effect of the gradual warming of the Holocene and the rise in sea level, this ice structure slowly lost stability. Until the moment when a structural weakness or a sudden rise in water level caused a bifurcation.

When the hydrostatic pressure exceeded the resistance of these structures, an instability occurred, leading to a catastrophic rupture. The system then transitioned from a metastable state (confined lake) to an irreversible dynamic state (massive drainage), in a process analogous to a phase transition. This bifurcation mobilized several thousand cubic kilometers of fresh water in a few months or years, triggering an abrupt forcing on the ocean circulation of the North Atlantic.

The Lake Agassiz catastrophe is a climate warning. The rupture of the glacial dam retaining Lake Agassiz illustrates a physical bifurcation: an abrupt and irreversible change triggered by reaching a critical threshold in a slowly constrained system. This nonlinear dynamic, typical of complex systems, is particularly concerning today.

Like past climatic events, current global warming could cause an unpredictable bifurcation, given the multiple and interconnected factors at play. As before, crossing a threshold could reorganize the global climate system within a few decades. These past tipping points help us better imagine future instabilities in an increasingly human-constrained climate.