Carbon is much more than a simple chemical element (C, atomic number 6). It is the foundation of organic life and one of the main regulators of our planet's climate. Its perpetual journey between Earth's major reservoirs—the atmosphere, hydrosphere (oceans), biosphere (forests, soils), and geosphere (subsoils)—forms a system of remarkable complexity and harmony.

The carbon cycle has gradually been understood as a complex network of flows and stocks, linking biogeochemistry and climatology. The identification of CO2 as a gas involved in exchanges between the atmosphere, oceans, and biosphere began with the experiments of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) and Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794), who demonstrated the role of plants in producing oxygen and absorbing CO2.

In the mid-19th century, Eunice Newton Foote (1819–1888) showed that CO2 absorbs solar heat, highlighting its role in atmospheric warming and thermal regulation—a key element in understanding the carbon cycle.

In the 19th century, studies on animal respiration and organic decomposition also showed that carbon could circulate between living organisms and the atmosphere. In the 20th century, the quantification of oceanic and terrestrial flows allowed the formalization of the carbon cycle, distinguishing between fast reservoirs (biosphere, atmosphere, surface oceans) and slow reservoirs (sediments, fossil fuels, lithosphere).

Today, the use of climate models and isotopic measurements allows precise tracking of carbon transfer between reservoirs and understanding the impact of human activities on atmospheric CO2 and global warming.

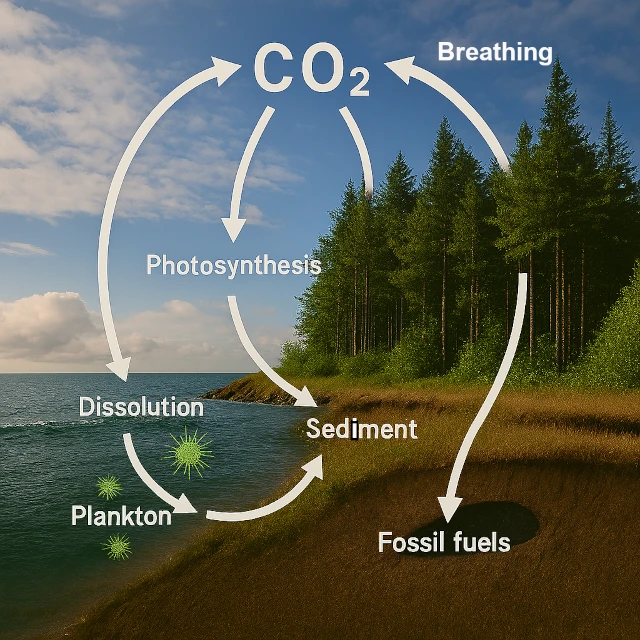

The carbon cycle is the set of physical, chemical, and biological processes that ensure the circulation of carbon between Earth's main reservoirs: atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere.

The carbon cycle operates on timescales that vary widely: from rapid exchanges between the atmosphere, biosphere, and surface oceans (years to decades) to slow transfers to sediments and the lithosphere (thousands to millions of years). This overlay of rapid and slow dynamics regulates Earth's climate and conditions the response to natural or anthropogenic disturbances.

| Source Reservoir | Stored Quantity (GtC) | Target Reservoir | Process | Annual Flow (GtC/year) | Dominant Transformation | Timescale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere (CO2) | ≈ 880 | Vegetation Biosphere | Photosynthesis | ≈ 120 | \( CO_2 + H_2O \xrightarrow{\text{solar energy}} CH_2O + O_2 \) (Reduction of mineral carbon to organic carbon) | Years |

| Vegetation Biosphere | ≈ 450 to 650 | Animal Biosphere | Transfer of Organic Carbon | ≈ 60 | \( CH_2O_{\text{plant}} \rightarrow CH_2O_{\text{animal}} + CO_2 \) | Years to Decades |

| Biosphere (Vegetation and Animals) | ≈ 2,000 (including soils) | Atmosphere (CO2) | Respiration, Decomposition | ≈ 120 | \( CH_2O + O_2 \rightarrow CO_2 + H_2O + \text{energy} \) (Biological oxidation of organic carbon) | Years |

| Atmosphere (CO2) | ≈ 880 | Surface Oceans | Oceanic Dissolution | ≈ 90 | \(CO_2 + H_2O \rightleftharpoons H_2CO_3 \rightleftharpoons H^+ + HCO_3^- \rightleftharpoons 2H^+ + CO_3^{2-}\) (CO2/HCO3-/CO32- equilibria) | Months to Centuries |

| Oceans (Dissolved Carbon) | ≈ 38,000 | Marine Sediments | Biomineralization | ≈ 0.5 to 1 | \(Ca^{2+} + HCO_3^- \rightleftharpoons CaCO_3(s) + H^+\) (Formation of CaCO3 carbonates) | Centuries to Millennia |

| Biosphere and Sediments | ≈ 15,000 | Fossil Fuels | Burial, Diagenesis | ≈ 0.1 | \(CH_2O_{\text{organic matter}} \rightarrow C_{\text{fossil}} + H_2O + CO_2\) (Concentration and fossilization of carbon) | Millions of Years |

| Fossil Fuels | ≈ 4,000 | Atmosphere (CO2) | Combustion | ≈ 10 | \(C_6H_{12}O_6 (\text{fossil}) + 6\,O_2 \rightarrow 6\,CO_2 + 6\,H_2O\) (Rapid oxidation of fossil carbon) | Instantaneous to Decades |

| Lithosphere (Carbonate Rocks) | > 60,000,000 | Atmosphere (CO2) | Subduction, Volcanism | ≈ 0.1 | \(CaCO_3(\text{sediment}) + \text{magma} \rightarrow CaO + CO_2(\text{volcanic})\) (Mantle degassing of carbon) | Millions of Years |

N.B.:

Vegetation absorbs atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis, but it also releases it during respiration and decomposition of organic matter. Thus, the biosphere acts as both a carbon sink and source, with a net balance that depends on seasonal flows and ecological disturbances.

N.B.:

Geological-scale climate equilibrium results from feedback between volcanic degassing (which releases CO2 from lithospheric reservoirs) and silicate weathering (which captures atmospheric CO2). Warming accelerates weathering, reducing CO2 and cooling the climate. This mechanism links carbon stocks and flows, acting as a slow but effective planetary thermostat.