Global dimming finds an increasingly evident explanation in the physics of global warming. A warmer atmosphere has an increased capacity to hold water vapor. According to the Clausius-Clapeyron relation: for each degree of warming, the air can retain approximately 7% more moisture. This water vapor, rising and condensing, fuels a denser and more persistent cloud cover.

This increase in cloudiness is not without consequences for the climate itself. Clouds play a dual role: they reflect some solar radiation back into space (umbrella effect), but they also trap infrared radiation emitted by the Earth (greenhouse effect). The net result of this cloud feedback is one of the greatest challenges of modern climatology. Recent satellite observations suggest that the cooling effect dominates in some regions, while the warming effect prevails elsewhere.

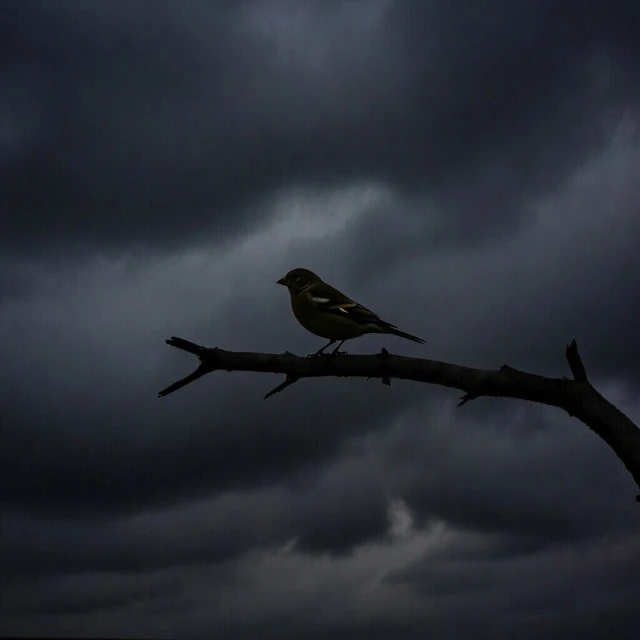

The consequences of this thermal dimming are already visible. The cloud invasion is the visible signature of climate change in action. It reminds us that every tenth of a degree of additional warming translates into more moisture in the air, more clouds, and a little less direct sunlight. There is a trend of increasing cloud cover in tropical and temperate regions, with grayer winters and summers where the sun struggles to break through.

| Climate Zone | Increase in Water Vapor (1990-2025) | Change in Cloud Cover | Impact on Sunshine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical Regions (Amazon, Congo Basin, Indonesia) | +6% to +8% | Marked increase in convective clouds | Decrease of 4% to 6% |

| Temperate Zones (Europe, North America) | +4% to +6% | Increase in stratus and stratocumulus | Decrease of 2% to 4% |

| Boreal Regions (Siberia, Canada, Scandinavia) | +5% to +7% | More frequent low clouds in summer | Marked seasonal decrease |

| Temperate South America (Argentina, Chile, Southern Brazil) | +4% to +6% | Increase in frontal cloudiness | Decrease of 3% to 5% |

| Southern Africa (Namibia, Botswana, South Africa) | +3% to +5% | More invasive maritime clouds | Decrease of 2% to 4% |

| Australia and New Zealand | +4% to +6% | Increase in coastal and cyclonic clouds | Decrease of 3% to 5% |

| Antarctic Region and Southern Ocean | +5% to +7% | More frequent low clouds, accelerated melting | Moderate decrease but complex albedo effect |

Source: NOAA Climate.gov and IPCC, AR6 WG1, Chapter 7 (2023), NOAA CPC.

This question pits two contradictory trends resulting from global warming against each other.

On one hand, the increase in water vapor (7% more per degree) fuels denser cloud cover, pushing us toward a darker and wetter world. Thus, the persistent dimming scenario predicts a significant increase in high clouds in the tropics and stratus in temperate zones, with a 5% to 10% decrease in sunshine by 2100.

On the other hand, the reduction in polluting aerosols makes clouds less reflective and allows more light to pass through, accelerating global warming. In Europe and North America, where anti-pollution standards have significantly reduced emissions since the 1990s, solar radiation has increased by 1% to 2% per decade since the early 21st century. Thus, the scenario of sudden brightening, following the rapid disappearance of aerosols, could reveal hitherto masked warming, triggering a "radiative collapse": a sky regaining its azure luminosity while the planet undergoes unprecedented thermal acceleration.

One certainty emerges: the world of tomorrow will be different from that of yesterday. Whether we are heading toward a darker or brighter world, these changes will have major consequences for ecosystems, agriculture, energy production, and human well-being.