At the beginning of electrification, in the second half of the 19th century, the electric current used in urban networks was mainly direct current. The first generators directly powered nearby lamps and motors. Voltages were low, distances short, and losses acceptable.

With the rapid increase in demand for lighting, motive power, and later household appliances, it became necessary to transport energy over tens, then hundreds of kilometers. Direct current then faced a simple physical limit: to transport a lot of power without excessive losses, the voltage must be increased and the current reduced.

Electric current exists in two complementary forms: alternating current and direct current. The former varies periodically, while the latter maintains a constant polarity. However, in modern systems, these two forms are not opposed: direct current is very often obtained by rectifying an alternating current.

Alternating current is generated directly by an alternator, whose rotation creates a sinusoidal voltage. This form of energy is ideal for high-voltage transport, as it can be easily transformed using a transformer.

Direct current, historically produced by dynamos, now mainly comes from the rectification of alternating current. Power electronics makes it possible to convert an alternating voltage into a stable direct voltage, used in batteries, electronics, storage systems, and HVDC links. Thus, modern direct current is not an independent form, but a transformation of alternating current.

The electrical power transported is given by \(P = U \times I\), where \(P\) is power, \(U\) is voltage, and \(I\) is current. For a given power, if the voltage is doubled, the current can be halved. However, Joule losses in the lines are proportional to \(I^{2} \times R\), with \(R\) being the resistance of the cables. Reducing the current is therefore the most effective way to limit losses over long distances.

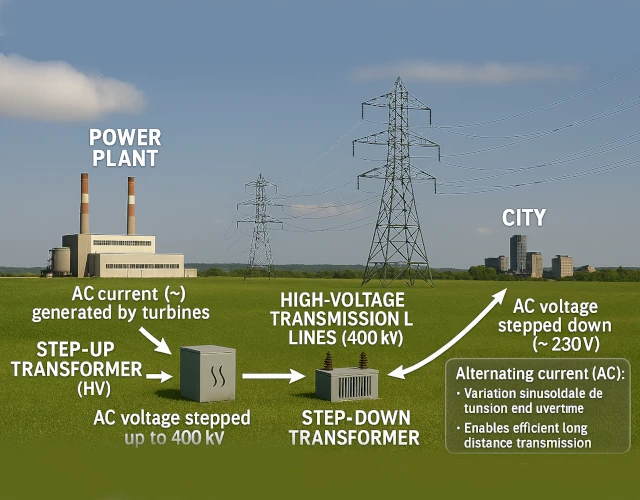

In practice, this leads to the use of very high voltages for transport, then to lowering these voltages as close as possible to the points of consumption. This is precisely what alternating current allows, thanks to a key device in electrical engineering: the transformer.

Consider an electrical power of \(P = 1\ \text{GW}\), which is the order of magnitude of the power provided by a nuclear reactor. Suppose this power must be transported over \(100\ \text{km}\) by a line whose equivalent resistance (round trip) is \(R = 3\ \Omega\), which corresponds to about \(0.03\ \Omega/\text{km}\). Let's compare transport at \(50\ \text{kV}\) and at \(400\ \text{kV}\), which is part of current standards.

1) Transport at 50 kV

The required current is:

\(I = \frac{P}{U} = \frac{1\ \text{GW}}{50\ \text{kV}} = 20,000\ \text{A}\).

The Joule losses are then:

\(P_{\text{losses}} = I^{2} \times R = (20,000)^{2} \times 3 = 1.2 \times 10^{9}\ \text{W}\).

The losses reach about 1.2 GW in the form of heat, meaning that much more than 1 GW would have to be supplied at the input of the line to deliver 1 GW at the other end. At such a low voltage, transport becomes totally inefficient.

2) Transport at 400 kV

The current becomes:

\(I = \frac{1\ \text{GW}}{400\ \text{kV}} = 2,500\ \text{A}\).

The associated losses are:

\(P_{\text{losses}} = (2,500)^{2} \times 3 = 18.75 \times 10^{6}\ \text{W}\).

Only about 18.75 MW is lost, which is less than 2% of the transported power.

By increasing the voltage from \(50\ \text{kV}\) to \(400\ \text{kV}\), the voltage is multiplied by 8, the current is divided by 8, and the losses are divided by \(8^{2} = 64\). With a realistic line resistance, it is clear that very high voltage is essential for transporting the power of a nuclear reactor with acceptable losses.

A transformer only works with alternating current. It is based on the temporal variation of the magnetic flux in an iron circuit, which induces a voltage in a secondary winding when a primary winding is powered. By adjusting the number of turns in each winding, the voltage can be increased or decreased very efficiently.

This property made it possible to structure modern networks in levels: production at medium voltage, elevation to very high voltage for transport, then gradual reduction to domestic voltages. Without transformers, each voltage level would have required specific machines and complex conversions. Alternating current thus became the simplest and most robust solution for an extensive network.

The famous "War of the Currents" opposed Thomas Edison (1847-1931), a proponent of direct current, to Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) and George Westinghouse (1846-1914), advocates of alternating current. Edison had already invested in direct current distribution networks and feared his business model would be challenged. Tesla, on the other hand, had designed polyphase systems particularly suited to alternating current.

Spectacular demonstrations of long-distance transport, such as powering the city of Buffalo from Niagara Falls at the end of the 19th century, showed the practical superiority of alternating current for large powers. Power plants could be located where primary energy was available, and electricity could be transported to urban centers with limited losses.

Alternating current has several major advantages for a large-scale network. First, the ability to easily transform the voltage allows each section of the network to be optimized according to the distance and the power to be transported. Second, rotating machines, such as asynchronous motors, are simple, robust, and inexpensive when powered by alternating current.

Furthermore, the synchronization of several generators on the same network is facilitated by the periodic nature of alternating current. Large continental interconnections rely on this property of synchronism. Finally, the measurement and protection of lines have historically been simpler with alternating quantities, which has contributed to the overall reliability of networks.

Direct current has not disappeared, however. With the rise of power electronics, it has become possible to efficiently convert alternating current to direct current and vice versa. High-voltage direct current links, called HVDC, are now used to connect distant networks or to transport large powers underwater.

In these applications, direct current offers advantages such as the reduction of certain losses and the absence of synchronization problems between networks. However, these systems still rely on an environment that is mostly alternating current, in which production, distribution, and most uses remain alternating. The historical choice of alternating current therefore continues to structure the overall architecture of our networks.

The success of alternating current is not just a matter of physics. It also results from a compromise between the technologies available at the end of the 19th century, infrastructure costs, and the industrial choices of the pioneers of electricity. Once the first large alternating current networks were built, standardization effects reinforced this initial choice.

Even today, the frequency of 50 Hz in Europe and 60 Hz in North America is a legacy of these historical decisions. Changing paradigms would involve modifying billions of devices and millions of kilometers of lines. Alternating current therefore remains the backbone of our electrical civilization, while direct current occupies specialized niches where its particular qualities are put to use.

| Characteristic | Alternating Current | Direct Current | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage transformation | Easy with a transformer | Long difficult, requires power electronics | Key point for long-distance transport |

| Line losses | Reduced thanks to high voltage | Reduced in HVDC over very long distances | Both solutions are now complementary |

| Rotating machines | Simple and robust asynchronous motors | More complex or specific motors | Historical advantage for industry |

| Network interconnection | Synchronization required | Allows connection of non-synchronous networks | HVDC used as a "bridge" between systems |

| Typical uses | Public distribution, industry, housing | Long links, electronics, storage | Hybrid AC + DC architecture |

Source: International Energy Agency – Electricity Information and CIGRE – Studies on HVDC links.