Every second, our bodies are traversed by billions of molecules carried by chance: some nourish, others transmit messages, some protect, and others are potentially dangerous.

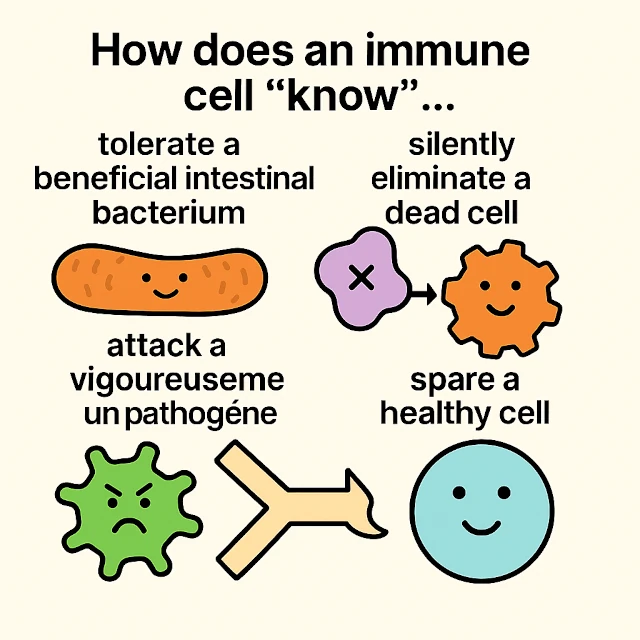

Among these molecules, some are part of us and are perfectly accepted. Others, like those in our gut microbiome, are foreign but tolerated. Finally, some are harmful: viruses, pathogenic bacteria, dead or cancerous cells. But how do our cells know what to tolerate and what to eliminate? This is where the distinction between "self" and "non-self" comes into play.

To understand this distinction, three major physical principles play a role: electromagnetism, thermodynamics, and quantum mechanics.

"Self" molecules naturally fit into their environment, like perfectly matched puzzle pieces. "Non-self" molecules create disturbances and do not integrate, triggering a physical response from the system.

A living organism is neither completely ordered nor totally chaotic. Molecules move unpredictably, but this local agitation allows the system to find stable configurations. This is what makes life both flexible and robust.

The function of a molecule is not innate: it appears when it fits into a network where its presence produces a useful and repeatable effect, like a gear in a well-oiled machine. It is a property that emerges from the overall organization.

DNA contains the instructions to make proteins. The cell first copies these instructions into a messenger RNA, which is then edited to keep only the useful parts. This RNA exits the nucleus and is read by a ribosome, which assembles the amino acids in the correct order to create a protein. Thus, the genetic code in DNA is transformed into living matter, and depending on the message carried by the RNA, the cell can produce a wide variety of proteins. This process illustrates how molecules interact and organize to create functional structures in a complex environment.

Image source: 3D Animation of DNA to RNA to Protein

Electrons and electrical charges determine how atoms assemble and what shapes molecules adopt. The shape (spatial conformation) is essential: it makes all the difference between a functional molecule and an inert clump. It allows a molecule to integrate correctly or, if it is malformed, to produce a disturbance in the system.

In an organism, molecules do not simply seek to be in the most stable state possible. They are maintained in configurations that allow the system to function, thanks to constant flows of matter and energy. This ensures that "self" molecules remain harmonious while "non-self" can be detected and eliminated.

At the level of electrons and atoms, quantum mechanics governs molecular compatibility. The "self" is characterized by the harmonization of its electron orbitals and charges. The "non-self" introduces quantum dissonances, tensions, and disturbances that betray its incompatibility.

The "self" establishes itself without an active selection mechanism: compatible molecular configurations spontaneously converge towards the state of least tension, like water flowing to the lowest point. The "non-self," by disrupting this balance, automatically triggers the physical processes that lead to its elimination.

Electromagnetism, thermodynamics, and quantum mechanics define "self" and "non-self," but it is a universal physical principle that explains their selection: any complex system spontaneously tends to maximize its internal coherence and minimize its energetic disturbances.

The "self" represents the set of molecular configurations compatible with this principle. The system does not have to choose it: the "self" establishes itself naturally, like water finding its lowest level. It emerges spontaneously from configurations that minimize internal energetic tensions.

Conversely, the "non-self" causes its own elimination. By disturbing the local balance, it triggers a cascade of physical events (electrostatic contrast, energy gradient, charge flow, thermal dissipation) that induce a spontaneous reorganization of the molecular environment: the system automatically adjusts its charges, realigns its structures, and equalizes its potentials to regain its minimal stability. The non-self thus becomes the architect of its own destruction.

The body does not "fight" disease: it restores order and coherence according to the laws of physics.

The immune system and the distinction between "self" and "non-self" can be understood as a natural consequence of electromagnetic, thermodynamic, and quantum interactions. Life spontaneously organizes its molecules to achieve a stable dynamic balance. Health, disease, and healing thus emerge from the fundamental laws of matter.