Bipedalism, or locomotion on two hind limbs, is a rare trait among mammals. Although most terrestrial mammals have been quadrupedal since the Triassic period (−251 to −199.6 million years ago), some groups have developed bipedal locomotion. Among hominids, it became dominant.

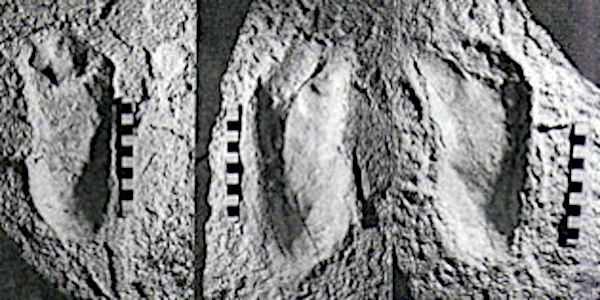

The first primates appeared about 70 million years ago. Orrorin tugenensis (≈6 Ma) has a femur suggesting an upright gait. Later, Australopithecus afarensis (≈3.6 Ma) exhibits bipedal characteristics confirmed by the fossil footprints of Laetoli (Tanzania). These footprints, attributed to A. afarensis, show a plantigrade gait similar to that of modern humans.

Bipedalism is not unique to humans. Birds (descendants of theropods), some mammals (meerkats, kangaroos, bears), and many primates (chimpanzees, bonobos, etc.) can adopt it temporarily. Among hominids, it became permanent.

Several hypotheses seek to explain the origin of bipedalism in hominids:

All these theories remain speculative. Fossils are rare and partial, making it difficult to reconstruct the evolutionary scenario. It is likely that several selective pressures—ecological, behavioral, dietary—jointly favored bipedalism.

The upright posture is common among arboreal monkeys, useful for climbing or hanging. It is plausible that the common ancestor of hominids retained this verticality when moving to the ground. Human bipedalism would then be a terrestrial extension of an arboreal adaptation.

Human bipedalism results from a slow evolutionary transition. It allowed the freeing of the hands, broadening of the diet, use of tools… but also imposes biomechanical constraints. This complex evolution illustrates the deep interaction between environment, behavior, and anatomy in human history.