Neanderthal man, or Homo neanderthalensis, was a human species that lived in Eurasia between approximately 400,000 and 40,000 years ago. Discovered in 1856 in the Neander Valley in Germany, this archaic representative of humanity was long considered primitive. However, recent research reveals a complex being, physically robust, adapted to glacial cold, but also endowed with elaborate social and cultural behaviors.

His elongated skull, prominent brow ridge, broad chest, and thick bones testify to his adaptation to the harsh environments of the Pleistocene. With a brain volume comparable to, or even larger than, that of Homo sapiens (about 1500 cm³), Neanderthal mastered fire, made sophisticated tools (Mousterian culture), hunted large mammals in groups, and buried their dead, a probable sign of some form of spirituality.

DNA analyses have revolutionized our understanding of Neanderthals. In 2010, the sequencing of their genome revealed that 1 to 4% of the DNA of current non-African populations comes from Homo neanderthalensis. This result demonstrates that interbreeding occurred between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, probably between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago during their coexistence in Europe and the Middle East.

The disappearance of Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago remains a subject of debate. Several hypotheses coexist: competition with Homo sapiens, rapid climatic changes, low genetic diversity, or a combination of these factors. Rather than a sudden extinction, some paleoanthropologists envision a gradual dilution into modern populations.

The study of Neanderthals sheds light on human evolution: they were neither a missing link nor a dead end, but a cousin branch, intelligent, ingenious, and deeply human. Their genetic, biological, and cultural heritage persists in our species, reminding us that evolution is more of a bush than a straight line.

The comparative study of the skulls of modern humans and Neanderthals highlights notable differences but also striking similarities, which testify to the evolution of our species.

The Neanderthal skull is generally longer, wider, and more robust than that of modern humans. Its face is more prominent, with strongly marked eyebrow arches, giving it a massive appearance. In contrast, the modern human skull is more rounded, with a less pronounced forehead and less developed eyebrow arches.

The lower part of the Neanderthal skull is wider, corresponding to a more robust jaw, adapted to more intense chewing, probably due to a diet based on tough meat and fibrous plants.

Although the Neanderthal skull is larger than that of modern humans in terms of overall volume, its brain was not proportionally larger. Indeed, the average volume of the Neanderthal skull is about 1500 cm³, while that of modern Homo sapiens ranges from 1300 to 1500 cm³. However, the Neanderthal brain had a different shape, more elongated, while that of modern humans is more globular.

One of the peculiarities of the Neanderthal skull is the orientation of its occiput. Indeed, its skull has a more pronounced slope at the back, with a more inclined cranial base, suggesting a less upright posture than that of modern humans. This may be related to differences in brain structure and motor control. This morphological detail reveals that Neanderthals had a slightly different posture, although they walked upright.

The Neanderthal skull has a thicker cranial box and particularly robust teeth, adapted to a difficult-to-digest diet. The teeth, especially the incisors and canines, are wider and more worn in Neanderthals, indicating intensive use of their teeth for activities such as cutting meat and handling objects. In contrast, modern human teeth are generally smaller and finer, adapted to a more varied diet.

Despite the obvious differences, the skulls of modern humans and Neanderthals share a number of characteristics. For example, both have a complex brain organization, although the anatomical configuration differs. Furthermore, certain aspects of the Neanderthal skull show traces of culture and innovation, such as toolmaking and the use of fire, which require some cognitive organization.

Neanderthal man, although distinct from Homo sapiens, is part of the human family whose history dates back millions of years. To understand its evolution, it is essential to examine the ancestors that marked its development within the Homo sapiens lineage.

The genus Homo, to which both Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis belong, emerged about 2.5 million years ago with the appearance of Homo habilis. The latter, the first representative of the genus Homo, had a larger brain than its australopithecine ancestors but was still partially adapted to an arboreal life. However, it marked a turning point with the manufacture of the first stone tools, thus giving birth to lithic culture.

Over millions of years, the evolution of hominids produced several important species, each marked by major innovations:

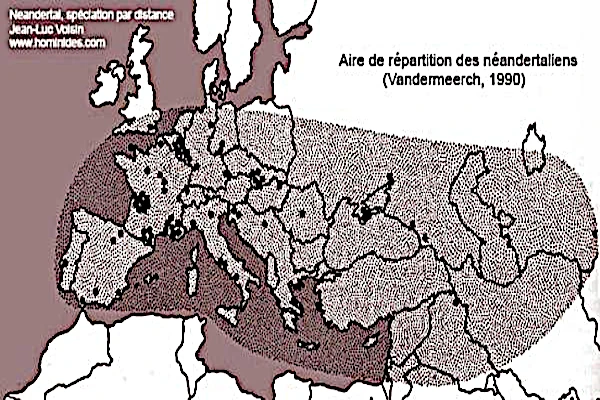

Fossils found in various regions of Europe and Asia indicate that populations of Homo heidelbergensis gradually adapted to cold environments and evolved into Neanderthals in Europe, while another branch of Homo heidelbergensis migrated to Africa, giving rise to Homo sapiens.

Thus, Neanderthal man is not an isolated species but part of a complex evolution where each ancestor contributed to the formation of unique characteristics that marked its adaptability and survival in a glacial environment before its extinction.