The Japanese satellite HINODE, launched in 2006 by JAXA in collaboration with NASA and ESA, specializes in observing the solar corona with extreme precision. During a solar eclipse, HINODE is not just a passive spectator: it becomes an advanced diagnostic tool for coronal plasma.

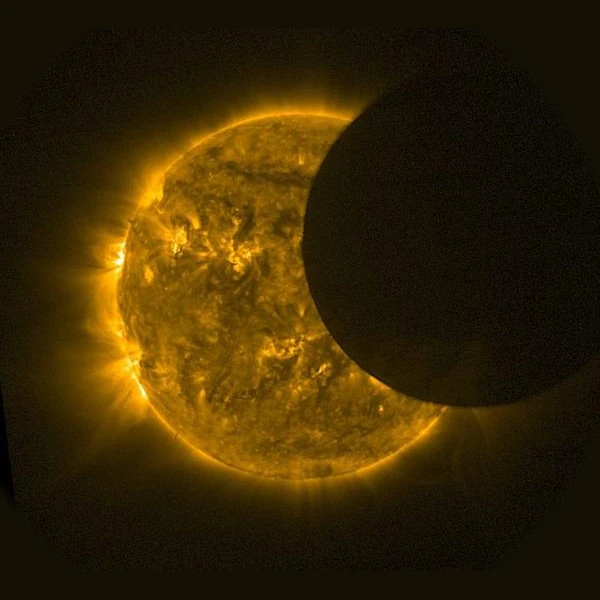

Thanks to its optical telescope (SOT) and X-ray spectrometer (XRT), HINODE records variations in intensity, temperature, and magnetic structuring in the solar corona, where the solar atmosphere extends hundreds of thousands of kilometers beyond the visible disk. During an eclipse observed on July 22, 2009, HINODE finely revealed dynamic coronal arches and ongoing coronal mass ejections (CMEs), thanks to the natural occultation provided by the Moon.

This spatial perspective eliminates terrestrial atmospheric disturbances, thus offering spectral and thermal profiles of rare precision.

The HINODE satellite, placed in a heliosynchronous orbit at about 600 km altitude, continuously observes the surface and corona of the Sun. During the partial eclipse of January 4, 2011, the satellite's trajectory allowed several passages of the lunar limb in front of the solar disk during its orbital revolution, known as multiple occultations.

The series of PROBA (PRoject for OnBoard Autonomy) satellites, developed by ESA, has also played a remarkable role in eclipse observation, particularly with PROBA-2, launched in 2009. This satellite is equipped with the SWAP (Sun Watcher using Active Pixel System detector and Image Processing) instrument, an EUV (Extreme Ultraviolet) camera that films the solar corona at wavelengths around 17.4 nm.

During eclipses, such as those of March 20, 2015, or August 21, 2017, PROBA-2 captured astonishing sequences where the Moon, partially or totally occulting the solar disk, allows detailed observation of coronal activity. Unlike terrestrial observations, limited by the atmosphere and the brief duration of totality, PROBA-2 records several passages of the lunar limb over the Sun during its polar heliosynchronous orbit.

The physical interest of these data lies in the dynamic mapping of solar magnetic field lines and the study of rapid fluctuations in EUV emission. These measurements, impossible to achieve from Earth, help feed space weather models, essential for predicting geomagnetic storms.