The Foucault Pendulum, named after the French physicist Léon Foucault (1819-1868), is an experimental device designed to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth. The first educational experiments titled "Come see the Earth rotate" were conducted at the Panthéon in 1851.

Today, the Foucault pendulum is a 28 kg lead and brass ball suspended from the dome of the Panthéon (Paris) by a 67 m long cable. A magnetic mechanism maintains its inertial motion, which due to air friction would only oscillate for 6 hours. Its swing allows us to see the Earth's reference points (ground, walls, dome of the Panthéon, etc.) rotate. In other words, we can see the Earth rotate without even looking at celestial objects (Sun, Moon, stars). The observer rotates with the Earth and remains stationary relative to the ground. For them, it is the pendulum's axis of oscillation that rotates.

This simple ordinary object forces us to accept several extraordinary notions as true.

All these notions are explained by a long mathematical development exposing the equations of the pendulum's motion. The oscillation period of the Foucault pendulum at the Panthéon is equal to 16.42 seconds because the length of the wire is 67 meters. The mass of the pendulum has no importance; the length of the wire is sufficient to calculate the oscillation period T.

T = 2π√l/g where l = length of the wire, g = acceleration due to gravity 9.81 m/s²

At a given latitude θ and an angular velocity of the Earth's rotation Ω, the rotation period is inversely proportional to the sine of this latitude, i.e., 2 π/Ωsin(θ). The sine of 30° being 1/2, a Foucault pendulum installed at a latitude of 30° will complete a full rotation in 48 hours. It is the Coriolis force, perpendicular to the displacement and proportional to the pendulum's speed, that deflects the pendulum from its initial plane of oscillation.

At the time of Foucault, there existed an absolute space relative to which all movements are defined. This immutable space was therefore a natural reference frame for the pendulum's oscillation. But today, space, or rather Einstein's space-time, is a dynamic entity, and the theory of relativity postulates that there is no privileged reference frame. In the universe, absolute motion does not exist; it is always relative to another frame that is also in motion. Yet we observe that the Foucault pendulum privileges a precise reference frame since its plane indicates a direction. But then, relative to what is the pendulum's plane fixed?

This unresolved enigma is still a subject of controversy.

At the North Pole, a Foucault pendulum suspended 67 m high and launched in any direction oscillates in 16.42 s. With each oscillation, its plane deviates by 7 mm. If the pendulum is launched in the direction of the Sun, it seems not to deviate relative to the Sun. But after a few hours, a deviation of the pendulum's plane is observed because the Earth/Sun direction is not fixed. Indeed, the Earth rotates around the Sun in 365 days, and thus the 7 mm deviation, 365 times smaller, eventually appears.

If not relative to the Sun, then relative to what is the pendulum's plane fixed?

If the pendulum is launched in the direction of any star in our Galaxy, it seems not to deviate relative to the star. Distant stars seem to be the reference frame relative to which the pendulum's plane of oscillation appears to be fixed. But after a few thousand years, a deviation of the pendulum's plane would be observed because the Sun/Star direction is not fixed. Indeed, the Sun rotates around the Galaxy in 250 million years, but the star also rotates around the Galaxy, and the two rotations are not synchronized. Thus, the deviation of the plane of oscillation relative to the star will eventually appear.

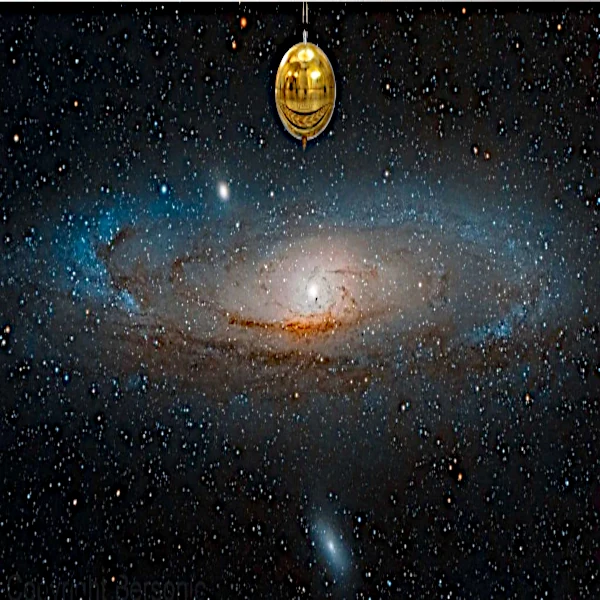

If not relative to the stars, then relative to what is the pendulum's plane fixed? The same would be true if the plane were oriented in the direction of a very distant galaxy. The drift time increases with the distance of the reference object. All reference points will eventually leave the pendulum's plane, but what reference point would remain in the pendulum's plane? At 13.77 billion years, the drift seems to stop, and the pendulum's plane remains fixed relative to objects close to the Big Bang. The direction of the Foucault pendulum, once launched, is not linked to the movement of our planet, our Sun, our galaxy, or distant galaxy clusters, but to the movement of the entire observable Universe.

The pendulum's axis then fixes itself immutably on this reference point!!!

170 years after its invention, the movement of the Foucault pendulum remains mysterious and unexplained. This seemingly insignificant mechanical object surprisingly transports us to the confines of the observable Universe.