At the end of December 2019, the ATLAS asteroid detection system spotted an unusual bright spot moving across the sky. Initial orbital calculations quickly revealed an extraordinary feature: its orbit was clearly hyperbolic. The object, designated 3I/ATLAS (or C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) in its initial cometary designation), was the third interstellar object ever discovered, but the first to show undeniable signs of cometary activity. Unlike its predecessors, this emissary was not a simple inert rock; it was alive, outgassing under the effect of the Sun, thus revealing its icy nature.

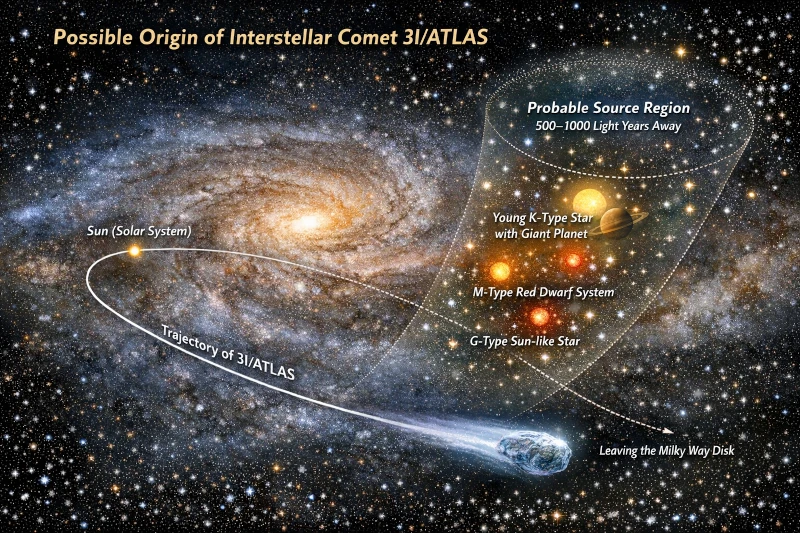

Estimates of the nucleus diameter range from about 0.44 km to 5.6 km based on Hubble images. Its speed at infinity, approximately \( v_{\infty} \approx 6.9 \ \text{km/s} \), and its hyperbolic orbit (eccentricity \( e \approx 1.0006 \)) proved that it did not originate from the Oort Cloud, the distant reservoir of the solar system's comets, but had been ejected from another planetary system, somewhere in the Milky Way. Its trajectory suggested that it would make only a single incursion into our system before continuing on an eternal journey through interstellar space.

Several telescopes and space missions contributed to the observations of 3I/ATLAS: Hubble Space Telescope, James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), Swift, SPHEREx, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe, and others produced imaging and spectroscopy data.

The apogee (or aphelion for an orbit around the Sun) only exists for closed elliptical orbits, i.e., those with an eccentricity less than 1 (e<1 → elliptical, e=0 → circular). However, 3I/ATLAS has a hyperbolic orbit (e>1). As a result, the object is not gravitationally bound to the Sun; it arrives from infinity, passes once through perihelion, and then departs forever. The distance to the apogee is therefore mathematically infinite, which prevents us from knowing its origin.

Estimated age (epoch of solid body formation) ≈ 1–3 billion years.

Interstellar drift time (time elapsed since the object was ejected from its original system) < 500 million years.

N.B.:

"3I" means the third interstellar object to have entered our system, after 1I/ʻOumuamua (2017) and 2I/Borisov (2019). The study of interstellar objects like 3I/ATLAS offers a unique opportunity to directly analyze matter from other star systems without having to send probes over impossible distances.

Spectroscopic analysis of the light from 3I/ATLAS, as it approached the Sun, allowed astronomers to determine the composition of its gases. The dominant emissions came from dicarbon (C2) and cyanogen (CN) molecules. This carbon-rich composition was intriguing and differed significantly from that of most comets in the solar system, which often show more varied CN/C2 ratios. This chemical signature could be the key to understanding the formation conditions in its original system, a system that may have been richer in carbon than ours, or subjected to different astrophysical processes during the comet's birth.

Unfortunately, the fate of this emissary took an unexpected turn. As astronomers around the world prepared to observe its perihelion passage, the nucleus of 3I/ATLAS began to fragment. Although this behavior has been observed in some "regular" comets, it prematurely ended the window for detailed observation. The emissary dissipated before revealing all its secrets, leaving behind a cloud of debris that continued on its hyperbolic trajectory.

| Object | Designation | Type | Estimated Size | Perihelion Distance (AU) | Year of Discovery | Physical Particularity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʻOumuamua | 1I/2017 U1 | Interstellar object (prob. asteroidal) | ~115 × 111 × 19 m | 0.255 | 2017 | Extremely elongated shape, non-gravitational acceleration without detectable coma. |

| Borisov | 2I/Borisov | Active interstellar comet | ~0.5 – 1 km | 2.006 | 2019 | Classic comet rich in CO and H₂O, confirmed sustained activity. |

| ATLAS (hypothetical) | 3I/ATLAS | Probable interstellar comet | < 1 km (estimated) | ≈ 1.36 | 2025 | Object on a hyperbolic trajectory, probably from another star system; origin and status still under analysis. |

Source: Data compiled from the circulars of the International Astronomical Union (MPC) and publications from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (NASA).

The discovery of 3I/ATLAS, shortly after that of 2I/Borisov, marked a revolution in our understanding of planetary systems. It suggests that the ejection of small icy and rocky bodies is a common phenomenon in the Galaxy. Scientists like Amaya Moro-Martín (1973-) have estimated that at any given time, thousands of such objects could be crossing the inner solar system, waiting to be detected.

Future large observatories, such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, whose operations began in the mid-2020s, promise to discover many interstellar visitors. Each will be an emissary, a witness capsule from elsewhere, offering a free sample of matter from another world. Their systematic study could inform us about the frequency of planetary systems similar to ours, or radically different, and about the violent processes (gravitational instabilities, migrations of giant planets) that populate the interstellar medium with debris.

3I/ATLAS, although ephemeral, marked a turning point. It proved that our solar system is permeable, constantly crossed by silent messengers from the confines of the Galaxy. Its furtive passage reminds us that we are not an isolated oasis, but an integral and connected part of a dynamic cosmos where matter, and perhaps one day the precursors of life, travel from star to star.