Optical illusions reveal the limits of our visual system. Our brain uses shortcuts (heuristics) to quickly interpret the world, but these mechanisms can be misled. As demonstrated by Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894), our perception relies on "unconscious inferences" rather than objective analysis.

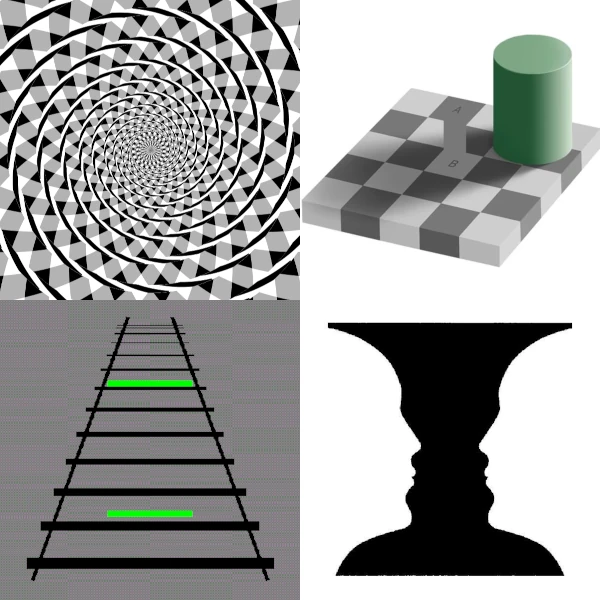

Edward Adelson's (1955-) illusion shows that two identical squares (A and B) appear to have different colors depending on their context: \(\square_A\) (dark gray) = \(\square_B\) (light gray) despite appearances to the contrary. This illustrates how our vision depends on relationships between elements rather than absolute properties.

Modern neuroscience (studies using fMRI) confirms that these illusions activate the same brain areas (visual cortex) as "real" perception, proving that the error lies in neural processing, not in the eye itself (as Johannes Müller (1801-1858) believed with his theory of "specific energies").

Three main categories emerge:

- Geometric illusions (e.g., Franz Müller-Lyer's (1857-1916) lines where < 63% of observers correctly perceive equal lengths)

- Chromatic illusions (e.g., Edward Adelson's checkerboard)

- Kinetic illusions (e.g., Charles Benham's (1831-1910) wheels creating subjective colors)

These phenomena have concrete applications:

- Graphic design: logos using ambiguous shapes (e.g., FedEx's hidden arrow)

- Road safety: 3D road markings to moderate speed

- Visual art: works by Maurits C. Escher (1898-1972) exploiting impossible perspectives

| Illusion type | Canonical example | Comment | Sensitivity percentage (general population) | Year of discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous contrast | Adelson's gray squares | Two squares of the same color appear different due to their immediate visual context, demonstrating how our color perception is relative rather than absolute. | 98-100% | 1995 |

| Forced perspective | Ponzo's railway | Two lines of equal length appear unequal when placed in a context suggesting depth, illustrating the influence of perspective cues on our size judgments. | 85-90% | 1913 |

| Illusory motion | Fraser's spiral | Although composed of concentric circles, the image gives the impression of an endless spiral, creating a sensation of continuous rotational movement. | 80-85% | 1908 |

| Figure/ground ambiguity | Rubin's vase | The image can be perceived either as a vase or as two human profiles facing each other, demonstrating how our brain alternates between different interpretations of the same image. | 95+% | 1915 |

Evolution favors speed over accuracy: as Mark Changizi (1968-) notes, "seeing the future" (anticipating movements) was more useful for our survival than perfectly perceiving the present. Our illusions would be "useful bugs" (TOI), optimized for natural environments but maladapted to artificial stimuli.