The three-body problem is one of the most famous and persistent enigmas in physics. Originally formulated by Isaac Newton (1643-1727), it poses a deceptively simple question: given the position, velocity, and mass of three celestial bodies (such as the Sun, Earth, and Moon), can we predict their future motion indefinitely using only the law of universal gravitation? The counterintuitive answer is no. There is no general and exact mathematical solution in the form of simple equations. Newton explicitly wrote that the motion of the Moon cannot be expressed by a simple closed-form formula.

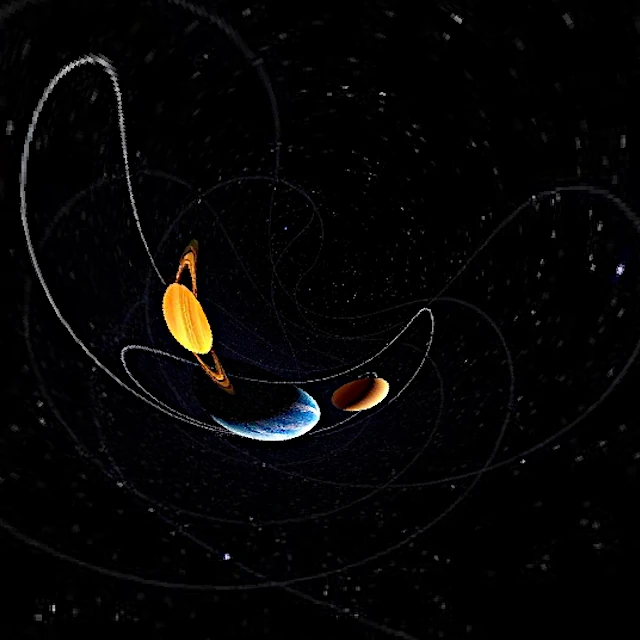

This impossibility is due to deterministic chaos. Whether gravity is described by Newton's law or Einstein's general relativity, three mutually interacting celestial bodies have their trajectories intertwined in such a sensitive way that an infinitesimal variation in their initial positions or velocities inevitably leads to radically different destinies: violent ejection, collision, or temporarily stable orbits. One fundamental law, but an infinity of possible destinies.

The search for a solution has mobilized the greatest minds. After Newton, mathematicians like Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736-1813) discovered particular stable configurations, the Lagrange points. These five points are oases of stability in chaos, used today to position space telescopes like James Webb. In the 19th century, Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) revolutionized the understanding of the problem by demonstrating that it had no general analytical solution. His work laid the foundations of modern chaos theory.

In the 20th century, the advent of computers made it possible to numerically simulate the equations and visualize the extreme sensitivity of three-body systems. This has profound implications for astrophysics: the long-term stability of certain planetary systems, the fate of stars in dense clusters, or the formation of binary black holes capturing a third companion.

| System Considered | Dominant Perturbations | Lyapunov Time | Reliable Prediction Horizon | Scientific Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun-Earth (idealized two-body) | None | Infinite | Unlimited | Isaac Newton (1643-1727) |

| Sun-Earth-Moon | Sun-Moon gravitational coupling | ≈ 5 million years | ≈ 10 to 20 million years | Jacques Laskar (1955- ) |

| Sun-Earth-Moon + Jupiter | Secular perturbations from Jupiter | ≈ 3 to 5 million years | ≈ 10 million years | Jacques Laskar (1955- ) |

| Sun-Earth-Moon + Jupiter + Saturn | Secular resonances Jupiter-Saturn, modulation of Earth's eccentricity | ≈ 2 to 3 million years | ≈ 5 to 10 million years | Jacques Laskar (1955- ) |

The overall stability of the solar system emerges from a dynamic balance far more complex than a simple fixed configuration. It is the result of the system's ability to explore, over cosmic timescales, a vast space of orbital configurations where gravitational forces balance out on average. Three fundamental theoretical pillars explain this phenomenon.

First, the constants of motion act as absolute safeguards. They delimit an accessible phase space that the system cannot leave, no matter how complex its evolution. Second, the hierarchical structure of masses (Sun ≫ Earth ≫ Moon) significantly reduces the amplitude of mutual perturbative interactions, keeping the core of the motion close to a stable Keplerian solution.

Finally, deep mathematical theorems describe this behavior. The KAM theorem explains why, despite chaos, "islands of stability" persist. Similarly, the concept of Arnold diffusion shows that exchanges of energy and angular momentum between bodies can be so slow that they are imperceptible over the lifetime of the solar system. Chaos exists, but it is confined within a basin of attraction with virtual but extremely effective walls.

Thus, the long-term unpredictability of the Moon's exact position does not prejudge the permanence of its gravitational association with Earth. The Sun-Earth-Moon system dances on a chaotic tightrope, but this tightrope is firmly anchored to the laws of conservation of physics.