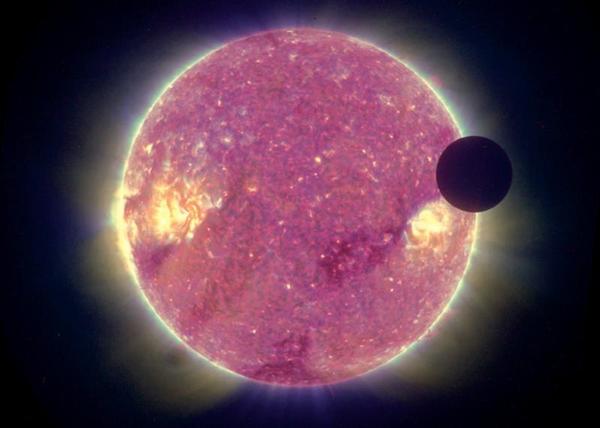

On February 25, 2007, a rare and spectacular astronomical phenomenon was observed: a lunar transit in front of the Sun, as seen from the STEREO-B space probe (Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory). Unlike solar eclipses visible from Earth, this transit was only perceptible from the particular position of this probe, placed in heliocentric orbit near Earth. This transit was immortalized by the SECCHI instrument (Sun Earth Connection Coronal and Heliospheric Investigation), which captured remarkably precise images showing the Moon as a perfectly circular black disk against the bright background of the solar corona. This kind of observation greatly contributes to the calibration of solar instruments, providing a well-defined reference to test the spatial resolution and photometric response of the sensors.

The Moon, devoid of an atmosphere, appeared in these images as a sharp black disk, contrasting strongly with the dynamic coronal ejections and solar plasma. This transit was also an opportunity for astrophysicists to better characterize the solar limb and validate emission models in the extreme ultraviolet. Since the Moon's trajectory in this case was not observable from Earth, only a space probe placed outside the Earth-Sun axis could record its details. The lunar transit in front of the Sun, although brief, demonstrates the importance of solar observation in stereoscopy, the main objective of the STEREO probes, which aim to understand the three-dimensional structure of the solar corona and the dynamics of massive coronal eruptions.

The interior of the Sun has such density and temperature that thermonuclear reactions occur, releasing enormous amounts of energy.

Most of this energy is released into space as electromagnetic radiation, primarily as visible light. The Sun also emits a stream of charged particles, called the solar wind. This solar wind strongly interacts with the magnetospheres of planets and moons and helps eject gases and dust out of the solar system. This wind emerges from the surface layers and propagates into space. Subjected to these gusts, comets adorn themselves with a tail showing the direction of the solar wind. Earth is not completely shielded by its magnetic shield; the solar wind, at a speed of 400 km/s, infiltrates through polar gaps, showing us magnificent northern and southern lights, with white, green, and red glows.

The Moon, like other objects in the solar system, also experiences the push of the solar wind. Studies conducted by several probes in lunar orbit have revealed the presence of an electric field on our natural satellite.

The deformable terrestrial magnetosphere extends about 60,000 kilometers but is halved when compressed under the push of intense solar winds. The magnetic shield partially prevents the solar wind from sweeping away the Earth's atmosphere.

The team of Andrew Poppe from the University of California, Berkeley, analyzed data provided by the Lunar Prospector, Kaguya, Chang'e, and Chandrayaan probes, and the two satellites of the Artemis mission (Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence and Electrodynamics of the Moon’s Interaction with the Sun). These lunar probes discovered a magnetic field on the Moon; it also has its own magnetic shield that extends up to 10,000 kilometers from the surface on the side facing the Sun.

The probes showed the solar plasma deforming, as if encountering a shock wave. This shield could result from an electric field that forms due to the bombardment of the lunar surface by ultraviolet solar light.